Mental Health Awareness Month: Psychosocial skills injection for teachers

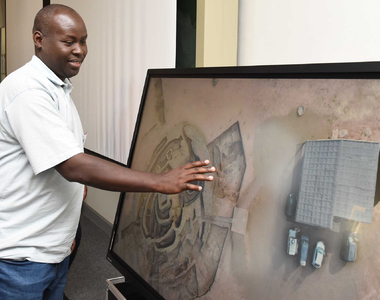

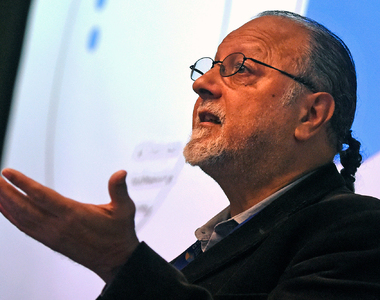

22 October 2021 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Lerato Maduna. Read time 9 min.

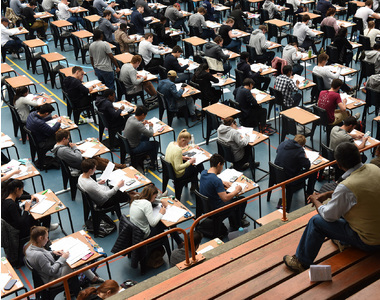

The slogan on the young matriculant’s T-shirt stood out: “Online Class of 2020”. The message was clear; it had been a year like no other for her and fellow learners. But others were not as successful. Unable to cope with class rotation, digital literacy and the complex psychosocial challenges wrought by COVID-19, learners across the country carried their problems into classrooms, creating a perfect storm for teaching staff – untrained in these skills, and struggling to cope themselves.

It was into this environment that the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Schools Development Unit (SDU) launched “Psychological First Aid for Educators (PFA) in the COVID-19 Context”. The certified short course is aimed at all teachers, especially Life Orientation and Life Skills teachers, as well as learning support assistants (LSAs), all of whom are increasingly having to deal with the psychological fall-out of the pandemic among learners. It also targets others in educational contexts, and community-based organisations.

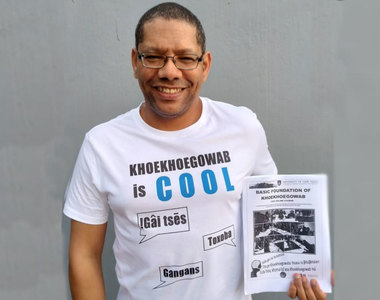

The course is convened by Ferial Parker, project manager of 100UP and 100UP+. The former is a schools intervention project that grooms learners in senior grades for university. The 100UP+ cohort are UCT students who have come through the 100UP programme.

“The psychosocial aspects of the pandemic and the emotional and psychological impact on our school-going youth is enormous.”

Parker’s co-developers are Dr Patti Silbert, project manager of UCT’s Schools Improvement Initiative (SII), and Tembeka Mzozoyana, a social worker in the SII and coordinator of the SII Schools Wellness Centre. They are supported by social worker Busisiwe Kokolo, and administrator Wadeeah Fisher.

“The psychosocial aspects of the pandemic and the emotional and psychological impact on our school-going youth is enormous,” said Dr Silbert, who recently co-authored an op-ed on the topic for The Conversation. “Education economist Martin Gustafsson has estimated that most learners could have lost almost 60% of their contact school days. The figure for children in the lower socio-economic groups is 65%.”

A further challenge is the increase in pregnancies and school drop-outs as a result, said Mzozoyana. Disruptions to routine and schooling have seen a spike in learner pregnancies at high schools – and this has spread to primary school level.

“And what’s happened over the past 18 months is that not only is there an increase in the number of pregnancies; the levels of complexities for the reasons girls are getting pregnant have also shifted,” said Mzozoyana.

Normalise vulnerability

Children who are hungry, stressed, afraid and traumatised cannot learn, said Silbert.

“This is a bio-psychosocial reality. The pre-frontal cortex shuts down. This is the centre of the brain where learning, creativity, understanding, trust, etc reside. We need to implement strategies that help our children and educators repair and heal, through re-connection with themselves and each other – by activating and strengthening the pre-frontal cortex.”

“We need to create school cultures of care, compassion and courage so that our learners are able to express themselves without fear.”

“If – as many trauma specialists suggest – trauma is about disconnection, it is imperative that effective psychosocial support strategies be provided to intercept ‘adverse childhood experiences’; and to help our youth reconnect with themselves, each other, and society at large.”

A key PFA objective is to help “normalise vulnerability” by creating what Silbert describes as “a classroom of psychological safety”, where learners can speak about their thoughts, feelings and experiences.

“We need to create school cultures of care, compassion and courage, so that our learners are able to express themselves without fear of humiliation or shame.”

The course equips participants with psychosocial support strategies that help their learners and are practical for their own self-care and self-development. They learn the basic skills of PFA using the RAPID (Reflective listening, Assessment of needs, Prioritisation, Intervention, Disposition and follow-up) psychological model, which they can apply immediately in their respective contexts with their learners.

The duration of the course in contact (teaching) time is nine hours. After completing all three modules, each participant is expected to complete an evidence-based task that demonstrates the key theoretical principles and the practical application of PFA in their particular context.

Over 300 primary- and secondary-school teachers have already registered for the course; and to date, 86 educators from the Western Cape, Gauteng and the Eastern Cape have completed the course and received their UCT certificate. Another cohort of 40 is due to complete the course soon. Principals, deputy principals and school management teams have also attended the course.

The team hopes that the Western Cape will roll out the course throughout the province.

The initiative is part of the Zenex Imfundo Phambili project. Zenex funded the course delivery to Grade 8 and 9 maths and English (First Additional Language) teachers. Most of the PFA participants fit into this category, said Silbert. The Zenex project has included LSAs in East London and Gauteng. These are post-matrics, placed in the schools to assist the teachers.

UCT’s SII has funded the delivery of two PFA educator cohorts from primary and secondary schools, across grades and subjects, from the eight SII partner schools – mostly in Khayelitsha.

“Predictions in current research are that it will take years for learning losses to be recovered.”

Interventions such as the PFA are critical, said Silbert.

“Predictions in current research are that it will take years for learning losses to be recovered; and that the impact of the pandemic has reduced the learning gains made over time, despite (in many cases) best efforts from teachers. Learning losses translate into lower performance and decreased attainment.”

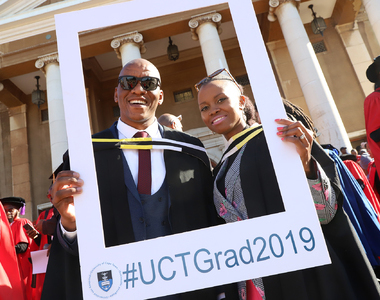

COVID-19 has also severely affected the SII and SDU’s work, said Parker, disrupting the gains made to transform the student cohort – which is vital to UCT’s Vision 2030, and its pillars of transformation, sustainability and excellence.

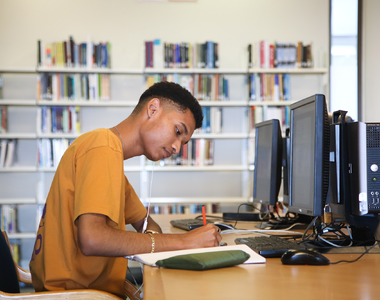

Based in the School of Education, the SDU’s 100UP programme has been affected by lockdown restrictions and moved to online engagement where possible, and the focus has shifted to curriculum support. But their Saturday classes have continued, said Parker.

“The attendance has been amazing. It just shows how much the students need help.”

The project team has also provided ongoing psychological first aid to the 100UP school learners and the 100UP+ students at UCT.

There has also been a shift in focus towards psychosocial support in several projects the SDU delivers. In the SII this is being achieved through the Schools Wellness Centre. Here Mzozoyana provides psychosocial support, both through delivering social work services herself, and through the social work students she supervises from UCT’s Department of Social Development. Third- and fourth-year students are placed in the partner schools for their professional practice.

‘No trauma is little’

Feedback from teachers who attended the PFA course underscores its value.

One participant wrote: “One aspect that still stands out for me even now is that ‘No trauma is little’ – that any traumatic experience deserves an ear and should be taken as just as important as those considered huge or great. And the way I listen now is more reflective, as I maintain eye contact and paraphrase and repeat what one said, to encourage the person to open up more and know that I am listening. People feel so much better knowing that their situation is not just any other situation … just offering an ear has had a positive impact.”

“We need to shift our mindsets from individual benefit to collective benefit.”

Silbert said that the lessons learnt during this time pointed to three main areas for intervention.

“First, we need to equip our low-socioeconomic-status schools with resources to become digitally literate, to ensure effective online teaching and learning in the event of further lockdowns. Second, we need to do far more to centre the voice of children, during and beyond large-scale situational crises. We need to encourage them to express themselves – and we need to listen to them. We also need to deepen our surge capacity as a society. This is the ability of a community to respond to the increased demand (surge) of psychosocial support in times of crisis.”

The third area for intervention relates to the value of PFA: “Every teacher should be taught some kind of PFA. Just as our physical health is dependent on the physical health of others, so our mental health is dependent on the mental health of others. We need to shift our mindsets from individual benefit to collective benefit. The trauma that we are facing in South Africa and globally is collective trauma – therefore, we all have a role to play in our collective healing.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.