TLC2023: Student assessment methods must be built on values and principles

24 November 2023 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 10 min.

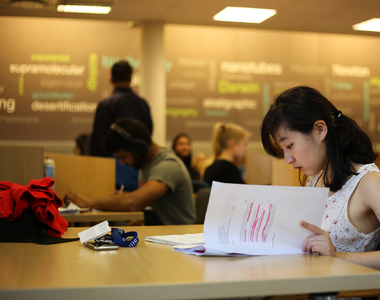

To address the complexities of the real world, universities must shift from a fixation on marks or grade ratings to transformative student assessment modes that value the social contribution students can make because they have engaged with knowledge in higher education settings.

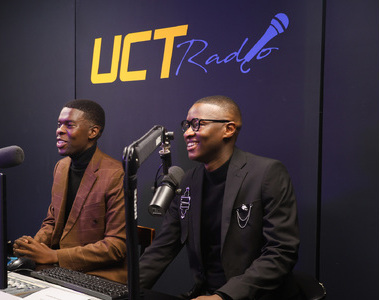

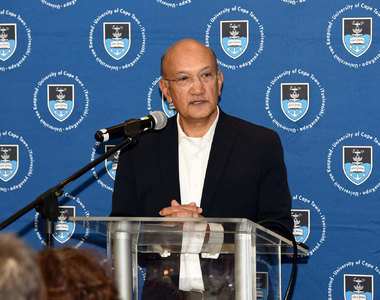

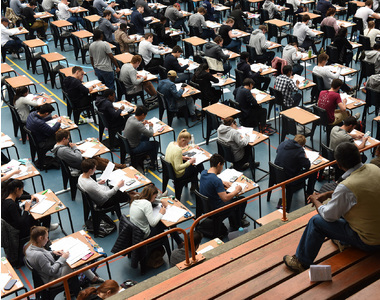

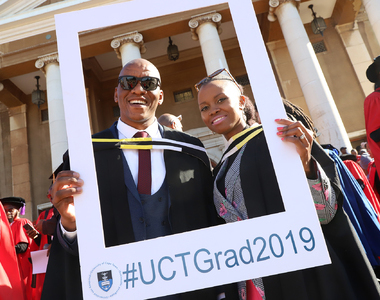

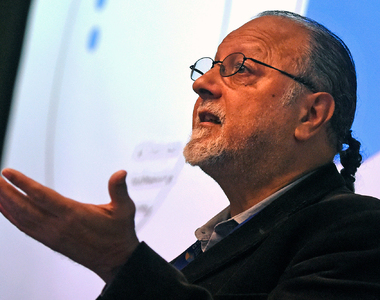

This message was the focus of Dr Jan McArthur’s virtual keynote address at the opening session of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) 2023 Teaching and Learning Conference (TLC 2023) from 21 to 22 November. The annual conference was organised by the Centre for Higher Education Development (CHED) and held in the Neville Alexander Building. Vice-Chancellor interim Emeritus Professor Daya Reddy opened proceedings, followed by a panel discussion.

Disentangle, and then build

It is through holistic and authentic assessment that universities realise their students’ potential, said Dr McArthur. She is the head of the Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom and co-researcher in the Centre for Global Higher Education, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, and Higher Education Funding Council for England. A widely published author on assessment, McArthur’s works include Assessment for Social Justice.

Her topic linked directly to this year’s TLC theme: “Assessment Entangled: Rethinking for Excellence, Transformation, and Sustainability”, which aligns with UCT’s Vision 2030 and a socially just teaching and learning environment.

“We must disentangle modes of student assessment before we can build. Authentic assessment looks at value, not performance,” said McArthur.

“How we respond to generative artificial intelligence [AI] and how we nurture holistic and authentic assessment must rest on values and principles that we should have attended to long before [the emergence of] generative AI,” said McArthur. “We need to reflect on what we’ve been doing – and get that right before we have any chance of realising the positive potential of AI.”

The notion of authentic assessment is often referred to in terms of “real-world tasks” and often conflated with the world of work, she said.

“If we’re not careful, it becomes about what employers want and about assessment for a compliant workforce.”

“Work is terribly important to our graduates but it’s not all there is. By referring to ‘the real’ world, we assume it is something external to our students; that they must prepare for; that they’re not part of. And our students, more than any generation, are very much part of the real world. But if we’re not careful, it becomes about what employers want and about assessment for a compliant workforce.”

Affirmative or transformative change

At the crux of this approach is what American philosopher, critical theorist, and feminist Professor Nancy Fraser refers to as a choice between affirmative change or transformative change. Affirmative change is linked to modes of assessment that seek to remedy societal problems but doesn’t address the underlying issues. A transformative approach puts the focus on the whole of society, with all the interrelationships and intricacies that it involves.

For example, an affirmative approach refers to “climate change”, whereas a transformative approach talks about the “climate emergency”.

So, if responding to a climate emergency, engineers will choose to build a factory in a way that responds to “emergency” and not “change” in terms of how it is built or how much pollution it generates.

“Authenticity is not to join the world that exists but to contribute to the world that could be. That’s how we build knowledge.”

“Their thinking extends to a whole-world solution,” said McArthur. “It includes the child down the road with asthma, or on the other side of the world. It transforms our society.”

Academic work engages with the minds of others and does not sit in a vacuum – and that must shape how universities approach assessment, she added.

“But faced with a very crowded curriculum, very few [students] made the link between the task and society. A crowded curriculum doesn’t allow time for reflection about the meaningfulness of the assessment.

“Authenticity is not to join the world that exists but to contribute to the world that could be. That’s how we build knowledge.”

Space for empowering assessment design

McArthur challenged the audience to think about spaces in their programme and assessment design that allows students to recognise their real achievements and their self-worth as members of society.

“Transformative assessment requires dismantling what exists, not build more on top. We have to go back and disentangle before we have any chance of building anew in the age of AI.”

Disentanglement, however, requires change at four main levels.

First, what counts as achievement? High marks?

“We’ve added ‘how much’ to assessment, which is not required by learning outcome,” McArthur countered. “Why have we done that and what does it mean?”

What does it mean to give a medical student 67% for an invasive biopsy procedure performed?

“We have allowed higher education to become obsessed by ‘how muchness’ and an obsession among students.”

“Does that mean that if the patient dies of blood poisoning after 10 days the student gets a higher mark than if the patient dies of blood poisoning after five days? We have allowed higher education to become obsessed by ‘how muchness’ and an obsession among students that can drive them to inappropriate or dishonest approaches to assessment.”

There are myths about how high marks incentivise learning, she said.

“But there’s no evidence of that. It’s an empty signifier of achievement. And there is pressure to replicate the competitive grading system in higher education.”

Meaningful assessment

Second, academia is trying to perfect the assessment process – and it’s the wrong way to think about it, said McArthur.

“Yes, there’s a right answer for the boiling point of a certain chemical (and don’t rely on ChatGPT to tell you), but we want to be building blocks for more complex forms of knowledge and we have to think about how we assess that in a meaningful way.”

Marking criteria and rubrics are intended to give precision to the marking process “for transparency and accountability”.

“But they can be very destructive,” said McArthur, “[acting as] a grid between me and a brilliant piece of work. And the real problem becomes the atomisation of assessment.”

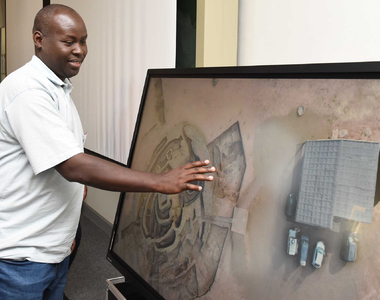

Using the example of John Glover’s historical painting of the Australian landscape (he was the first European to paint a local landscape), McArthur said that atomising the artistic assessment would be meaningless.

“Ultimately, assessment is about this big picture ... about its history. It’s not just colours on a canvas, it’s an understanding of what this painting represents. It can’t be about just one part. Students must understand the whole canvas they are working on. And that gives them their sense of achievement.”

Technology not the silver bullet

Third, McArthur said technology should not be used to absolve universities of their responsibility to “teach the academic craft and to assess it in authentic, honest and genuine ways”.

“There’s a conflation of technology and innovation in higher education and there’s this inevitability argument: that we must use technology for everything. If you’re not using it, you’re old fashioned and have no imagination. That’s hugely problematic. We must return to the question of why we assess. We assess to make judgement and we can’t skip that responsibility.”

Technology such as Turnitin, while a well-meaning attempt to curb plagiarism, could make students fearful or tentative about engaging with the minds of others, said McArthur.

“Authentic assessment is not to join the world that exists but to contribute to the world that could be.”

“Because the more engagement, the higher the originality score and in some cases that automatically triggers a plagiarism hearing. The student may have written a terrific assignment but removes a reference to [Karl] Marx to reduce their originality score to below 20%. This is hugely damaging. We have often conflated poor referencing skills with plagiarism.”

Fourth, authentic assessment is what German social philosopher Axel Honneth describes as “What is just is that which allows the individual member of our society to realise his or her own life objectives in cooperation with others, and with the greatest possible autonomy”.

“Authentic assessment is not to join the world that exists but to contribute to the world that could be,” said McArthur.

What the world needs

Lastly, she challenged different sectors of the university community to think about their own roles in the overall picture.

“University managers, what is your role in better, just and authentic assessment? Academics, how easy is it to reform assessment? Do you really believe in your assessments? Students, are you sending mixed messages to your teachers, saying you want to learn but obsessing about a mark? I understand that you are, but we must be on the same team here. Professional and services staff, has procedure overtaken purpose? Career services staff, are you promoting the education as competition narrative?

“And if we’re going to be criticised for something, rather let it be something we believe in; something based on years of credible educational research, something hopeful and joyous. And something that might just nurture our graduates to deal with the world around us – which isn’t looking all that happy or healthy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.