Decolonisation in the context of Vision 2030

28 September 2020 | Story Carla Bernardo. Read time 7 min.

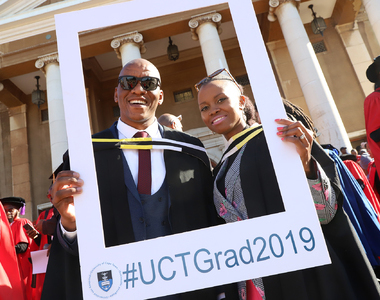

How will the University of Cape Town (UCT) embed decolonisation in Vision 2030, the institution’s new strategic vision? How will the university embed decoloniality as it unleashes human potential for a fair and just society? And what does it mean to be a global university in Africa?

These were the questions posed during a panel discussion on decolonisation in the context of Vision 2030. The discussion was part of a three-hour webinar on decolonisation and decoloniality, hosted by UCT on Tuesday, 22 September.

The panel discussion, which was moderated by Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Transformation Professor Loretta Feris, followed presentations by three recipients of the university’s decolonisation grant, and a UCT alumna.

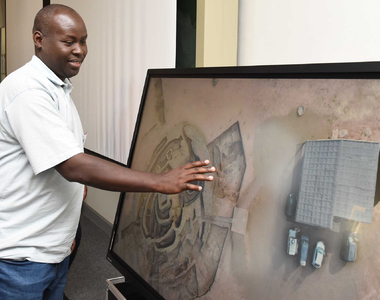

The recipients were Associate Professor Shose Kessi, the dean of Humanities and the co-director of the Hub for Decolonial Feminist Psychology in Africa; the head of UCT’s Archaeological Materials Laboratory, Professor Shadreck Chirikure; and a lecturer in the Political Science department Dr Lwazi Lushaba, who spoke alongside UCT alumna and Fulbright scholar Ziyana Lategan. Professor Floretta Boonzaier, another grant recipient and the co-director of the Hub for Decolonial Feminist Psychology in Africa, was unable to join the discussion.

Speaking on the panel were four renowned UCT scholars who work in the area of decolonisation:

- Professor Elelwani Ramugondo (Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the co-chair of UCT’s Curriculum Change Working Group from 2016 to 2017)

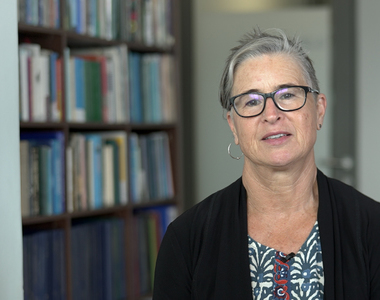

- Professor Rebecca Ackermann (Department of Archaeology, the director of the Human Evolution Research Institute and the deputy dean of transformation)

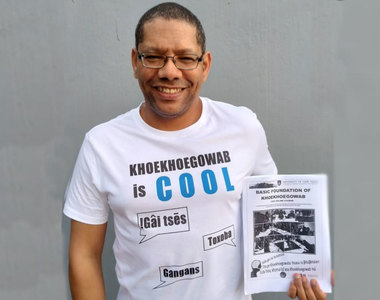

- Dr June Bam-Hutchison (Centre for African Studies, the interim head of the newly launched San and Khoe Research Unit who led, in partnership with the A/Xarra Restorative Justice Forum, the co-design processes of the renaming of the Jameson Memorial Hall to the Sarah Baartman Hall, and the introduction of the historic inaugural certificated foundational Khoekhoegowab at the university)

- Dr Kasturi Behari-Leak (Centre for Higher Education Development, the interim director of the academic staff and professional development centre, and the president of the Higher Education Learning and Teaching Association of Southern Africa).

Embedding decolonisation

For Dr Bam-Hutchison, indigenous ways of knowing must inform Vision 2030, a practical example of which is the work she has led in collaboration with the A/Xarra Restorative Justice Forum. From their years of work, certain factors have emerged as necessary for the act of decolonising. Crucial to decoloniality is multilingualism, critically understanding the formation of knowledge production processes, as well as interdisciplinarity – it cannot occur without these factors.

Bam-Hutchison also emphasised the importance of recognising prior learning to grow a cohort of scholars who will make a difference in the communities from which they emerge.

“It’s really about validating [and] theorising knowledges that have been on the periphery; people with these archives on the periphery and restoring as well as centring archives that have been lost due to colonialism,” she said.

According to Professor Ackermann, it is important to acknowledge her privilege but, even more so, to do something with it. Part of Ackermann’s decolonial work includes “actively working to stitch black and female postgraduates” into the academic networks she has been afforded access to because of her race and nationality as a North American. And this must be done in a way that centres and values black and female voices.

The paleoanthropologist added that decolonisation means owning the fact that her discipline has a dark history of racism and othering. It also means, more broadly, valuing diversity in research.

“Diverse and intersectional teams produce better science because they’ve got this rich, complex heterogeneity of thinking and practice,” said Ackermann.

Global, African university

When asked what it means to be a global university in Africa, Dr Behari-Leak noted that the very question surfaces the tension between being globally relevant and locally authentic. This, she said, is the decolonial work the university must do.

Included in this work is acknowledging that UCT is “not an island unto itself”.

“There are 25 other universities in the country that we need to demonstrate a relational ontology with, and how we are growing together as part of South Africa, into Africa,” said Behari-Leak.

In her final remarks, Professor Ramugondo said that the question of being a global university in Africa pushes UCT to “reckon with the fact that we may be ambivalent about our Africanness”.

“Perhaps, as we think about a university, a global university, which finds itself in Africa, we are to ask ourselves: What do we mean by global? Do we mean the whole world with everyone in it? Or are we talking about a slice of the global?

“When we talk about global, to what extent are we resisting that allure, that attraction to a global that leaves many behind? And I think we ought to ask ourselves a very difficult question about on whose behalf we speak,” said Ramugondo.

She added that in calling UCT an African university, the question must be asked as to whether someone from communities such as Nyanga, Bonteheuwel, Bishop Lavis, Gugulethu and Soweto are included.

“Or are we going to find ourselves with Vision 2030 seeing less of exactly those people that would want to call this their university too?”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.