Language for learning mathematics in multilingual classrooms

09 July 2019 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Brenton Geach. Read time 7 min.

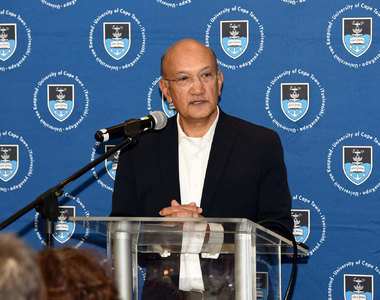

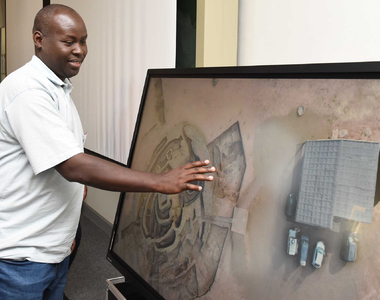

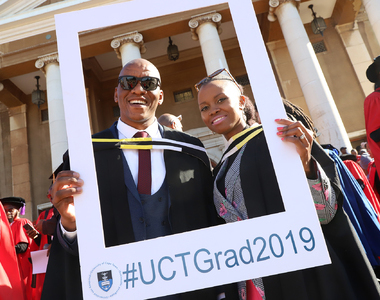

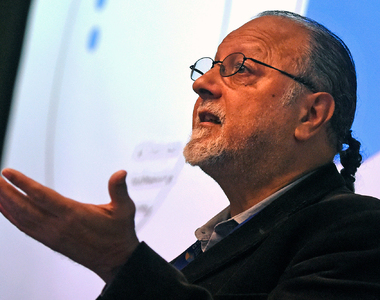

The need to address the complexities of language and communication for learning mathematics in multilingual classrooms is relevant not only to the University of Cape Town (UCT) but to the entire country, Vice-Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng told a meeting of experts in mathematics education and in literacy and language who gathered for a specialist symposium at the university last week.

The “Theories and research approaches on language and communication in multilingual mathematics classrooms” symposium, hosted by Phakeng in partnership with the Centre for Higher Education Development, saw delegates share experiences from across the world, examining theories and research approaches being used globally to understand the issue – and the consequences for knowledge building of the chosen theoretical frameworks

“The problem we are addressing is not just a problem of mathematics education … it is a problem that matters for our country,” Phakeng said.

The vice-chancellor, herself an esteemed professor in mathematics education, shared some of her insights about mathematics learning in multilingual contexts, and committed herself to further tackling the problem through her research.

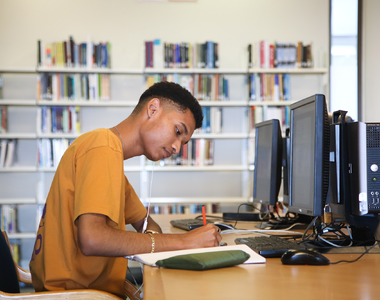

Phakeng acknowledged that she couldn’t assume “language in and of itself will solve the problem” of poor mathematics performance in South Africa. Yet she noted that for youngsters being taught the subject in a language other than their mother tongue – usually also among the most impoverished in South Africa –language matters in terms of the teaching and learning process, as well as their performance.

Why it matters

There are numerous reasons, she stressed, why language in multilingual mathematics classrooms matters. Some stakeholders are interested because of the “politics of language”.

“It’s about which languages are privileged and which ones are marginalised [and] silenced.”

“It’s about which languages are privileged and which ones are marginalised [and] silenced.”

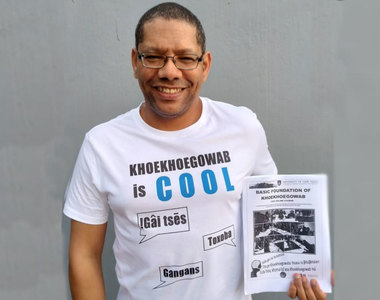

While democracy has brought about the recognition of 11 official languages, in practice only two of those languages continue to hold prominence – English and Afrikaans, Phakeng added, pointing out that a command of these languages continues to afford the speakers social capital and access to social goods.

While other stakeholders are interested in the topic because of its relevance to the decolonisation project, language has not featured prominently in this debate, which itself takes place in English.

Then, she said, there are also stakeholders outside of South Africa and the African continent who are dealing with their own complexities regarding language in mathematics classrooms.

“Multilingualism is not just a phenomenon in South Africa or on the continent; it is a phenomenon across the world.”

To tackle the complexities, there have been global moves in this area. These have included a shift from a focus on bilingualism in classrooms to multilingualism, which has also taken place at a theoretical level.

Initially, Phakeng said, research in the area was framed by a cognitive approach, with a subsequent move towards social perspectives on language.

“I argued that language is political in mathematics; that the way language is used in mathematics classrooms in South Africa or anywhere else in the world is not innocent …” she said of her research.

But rather than perpetuate dichotomies between theories, she stressed the need to bring theoretical approaches together to address pressing practical problems.

“We need these different theoretical voices to have a conversation … Because if they are not in conversation, then we will not be able to answer the questions on the ground.”

Different contexts

Phakeng invited three of her peers from universities abroad to the symposium, to help tackle the issue. She said they offered perspectives “from three different countries and three different multilingual contexts”, along with insight into the kind of theories colleagues are using.

“We need these different theoretical voices to have a conversation … Because if they are not in conversation, then we will not be able to answer the questions on the ground.”

At the UCT symposium, Professor Susanne Prediger from TU Dortmund University in Germany presented on “Understanding and fostering the learning of language learners: Overview on a chain of projects with different research approaches”.

Professor Arindam Bose from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in India spoke about “Fostering meaning-making in mathematics classrooms: Valuing tri/multilingual registers and spaces of learning”, while Professor Richard Barwell from the University of Ottawa in Canada presented on “Mathematics learning in second language classrooms in Canada: Dialogic perspectives”.

All three also join her this week at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education hosted by the University of Pretoria.

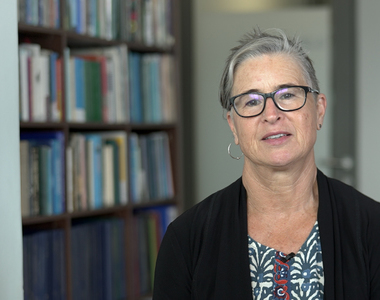

UCT’s Associate Professor Kate le Roux, from the Language Development Group in UCT’s Academic Development Programme, concluded the day’s presentations with her conceptual paper, “Africa-centred knowledge about multilingual school mathematics classrooms in South Africa”.

It concerns the geopolitics of knowledge production about teaching and learning in multilingual school mathematics classrooms. The focus is on the relationship between, on the one hand, the choice of research theories and methodologies and where research is conducted, and on the other, what knowledge is produced about teaching and learning in these classrooms.

She drew on an Africa-centred knowledges approach, located in Southern Theory, in a review of research on mathematics learning in multilingual classrooms in South Africa, conducted by researchers such as Phakeng and collaborators in South Africa, Africa and elsewhere.

Le Roux argued that their research process has not been a simple application of knowledge developed elsewhere in dominant “centre” contexts. Rather, the knowledge produced in the “periphery” context of South Africa can be viewed as a reflexive contribution to global knowledge in three respects: contributing a complex multilingual context; offering new perspectives on conceptions of language, and mathematics learners and teachers; and new research methods.

A “nuanced view of knowledge production practices in periphery contexts such as South Africa is important”, she added. This is so contributions to global knowledge of research situated in different contexts are recognised.

The symposium ended with summaries of the presentations and discussions by two discussants from UCT, Associate Professor Carolyn McKinney (School of Education) and Jumani Clarke (Numeracy Centre, Academic Development Programme).

They identified as a key theme the need to move beyond dichotomies, both in terms of how language use in mathematics classrooms is viewed, and the theories chosen to research such language use.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.