Best little (sustainable) house in Africa

01 October 2019 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Team Mahali. Read time 8 min.

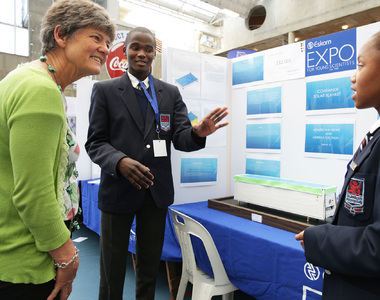

A solar-powered, “green” house designed and built by staff and students of the University of Cape Town (UCT) and Stellenbosch University (SU) has been awarded second place in the architecture category of the continent’s first Solar Decathlon Africa title in Morocco. The project was initiated by Stellenbosch University’s Sustainability Institute and the entry goes by the name of Team Mahali.

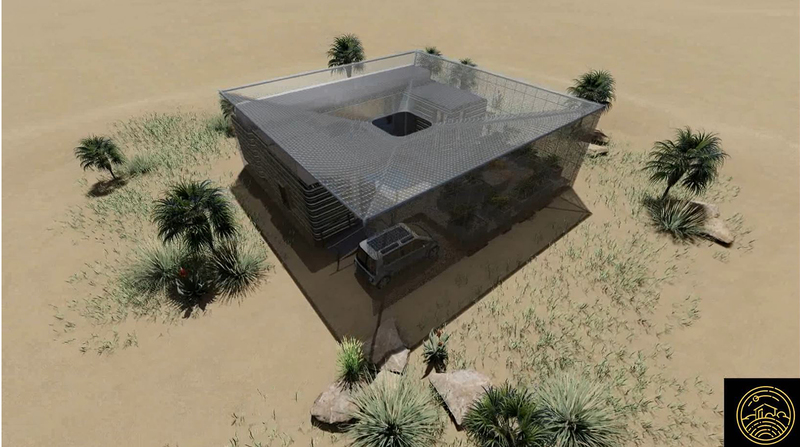

Team Mahali’s fully functional, modular, net-zero-energy house was erected and completed in a solar village of 18 houses in Benguerir, north of Marrakesh. It was just one of the creations of teams from competing universities around the world, all vying for the title of best sustainable house powered solely by the sun.

Team Mahali was the only sub-Saharan team chosen to participate in the competition. The brief was to design an affordable house of between 55 and 110 square metres, using local ingenuity, craftsmanship and materials, and suited to the African context.

Team Mahali’s design used a converted 12-metre, side-opening container shell for the main living space. Attached timber pods provided additional living room. House Mahali was designed and configured along the lines of a traditional Moroccan riad, which was reflected in its central courtyard and water feature.

“These designs have been used for centuries for their exceptional performance in terms of climate control, security, privacy, flexibility and adaptability,” said senior lecturer Michael Louw, of UCT’s School of Architecture, Planning & Geomatics.

Other UCT staff involved in the bid were Kevin Fellingham and John Coetzee, while the project leader was Sharné Bloem from SU.

Eco innovations

A tensile structure covers the building’s footprint, providing shade and collecting water from rain and condensation. This filters into the central pond, acting as a passive cooling device, before being pumped into a storage tank. The water captured in the pond assists with evaporative cooling while a water bladder under the patio area can be channelled to misters on the courtyard’s perimeter beam, or used for watering homegrown, organic plants.

Besides rainwater harvesting, the water system includes a dry toilet with waterless urinals, a kitchen grey water reclamation system using grease traps, aerated taps and an instant hot water system. All these approaches try to reduce water consumption and promote recycling.

The entire vertical perimeter, except for the entrance, is partly covered with retractable canvas sheeting to create a cooler interior and reduce dust, as well as provide privacy. Solar energy is captured by thin-film photovoltaics (PV) lining the tensile roof.

“We adopted a biomimicry approach and used the symbolism of a tree to shape our house.”

“Mahali’s African inspiration stretches beyond the borders of conventional design,” Louw explained.

“We adopted a biomimicry approach and used the symbolism of a tree to shape our house. Mahali’s notion of a tree is a steel frame that supports the tensile covering, which in turn accommodates the thin-film photovoltaic panels. This provides both shade and energy. It’s supported by four columns that define the four corners of the central water feature.”

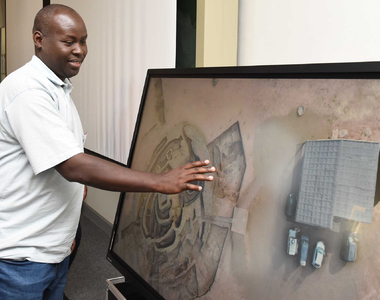

Perhaps the most striking visual aspect of House Mahali is its novel, colourful cladding, handcrafted by unemployed women at the Plastic Project in Franschhoek, a social and ecological initiative. Old plastic bags are collected (thanks to all those in the Faculty of Engineering & the Built Environment who contributed) and made into plastic yarn, or “plarn”, which they crocheted together to make cladding for the eco house – 558 wall panels worth R50 000 covering 250 square metres, almost all the external walls.

Power pride and joy

But House Mahali’s solar PV system is the team’s pride and joy, said Louw, and took many hours of design and research.

“We used the latest membrane integrated PV modules, which are flexible and can be glued directly onto the canvas, eliminating the need for heavy mounting structures, and they don’t compromise high wattage or efficiency.”

The team’s design uses the grid as a “battery”, allowing them to export excess energy during the day and draw that energy back during non-sunlight hours.

“The system will allow us to generate 15 305 kWh and offset our consumption of 14 500 kWhs on an annual basis. At the end of one year we should be net-positive with excess energy of 805 kWh per annum,” he explained.

“Because the Mahali house was constructed with the guiding principles of circular resource usage, biomimicry and solar technologies, our house is not only cheaper, with an exponentially lighter carbon footprint, but it will be able to pay for itself through the retail of surplus energy and carbon credits.”

The construction process aligned these very different aspects, Louw added.

“We’re merging very hi-tech digital design and manufacturing with traditional crafting in the making of an identity [for the house].”

“We’re merging very hi-tech digital design and manufacturing with traditional crafting in the making of an identity [for the house].”

Apart from these sustainable elements, each “living-ready” home entered into the competition had to be equipped with furniture and appliances to operate like a regular home would. The construction phase closed on 13 September and the formal part of the competition finished on 27 September.

Sustainable elements

Each entry was judged in 10 separately scored contests: architecture; engineering and construction; market appeal; communication and social awareness; appliances; home life and entertainment; sustainability; health and comfort; electrical energy balance; and innovation. Designs also had to include provision for a solar battery powered car.

As the competition’s goal was to promote sustainable housing, the structures such as House Mahali use natural and upcycled materials, solar energy only and come equipped with technically-advanced building and energy technologies.

In a project of this scope and size, there were challenges, said Louw. Students graduated and left, and team members changed. Funding was also a major constraint. Fortunately, the team secured funding from the Moroccan government and the hosting organisation, while they also managed to raise some money for the Plastic Project through online crowdfunding.

“It never goes entirely as planned or designed, but it’s pretty close to what we’d planned.

“It’s been such a long and challenging project that I thought it might not actually happen. But despite uncertainty, we stuck to our core aims.”

What happens to these homes once the competition is over?

“The organisers are planning to buy a few to become part of their Green Energy Park,” he said.

“Or they might use them as demonstration units to do comparative monitoring of energy collection, insulation and indoor climate. Others will be offered for sale or dismantled and shipped back to the respective team’s country of origin.”

- The competition was organised by the Moroccan Research Institute in Solar Energy and New Energies and the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, under the aegis of the Moroccan Ministry of Energy, Mines and Sustainable Development, with the support of the US Department of Energy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.