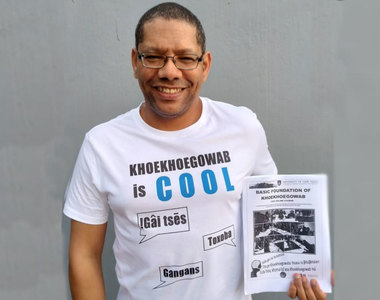

First certified foundational Khoekhoegowab course for SA

21 December 2020 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Bradley van Sitters. Read time 8 min.

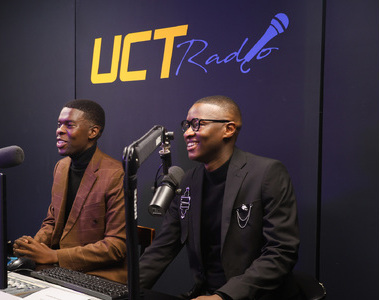

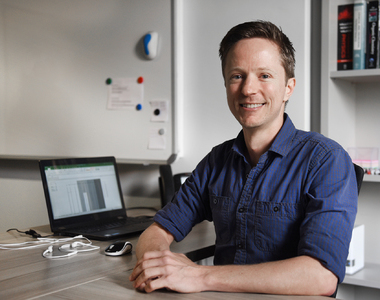

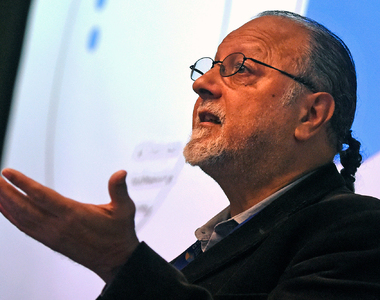

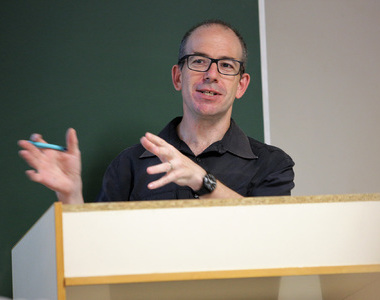

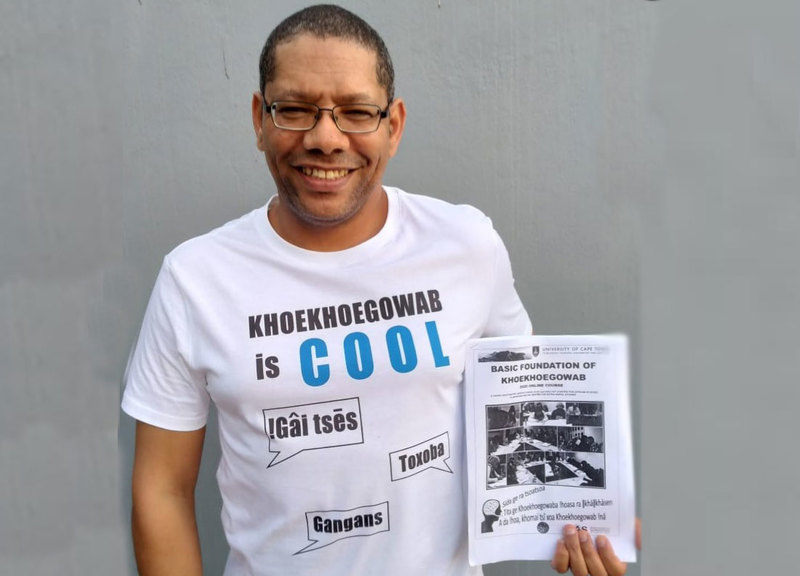

The intergenerational transmission of the indigenous Khoekhoegowab language will be essential to its survival, activist and teacher Bradley van Sitters said at the culmination of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) first online foundational Khoekhoegowab course, designed to revitalise the language.

Indigenous language regeneration is part of the African Renaissance, added Van Sitters.

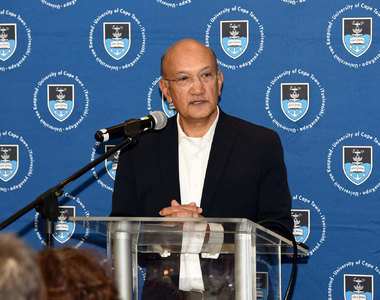

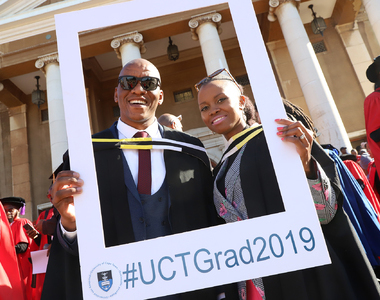

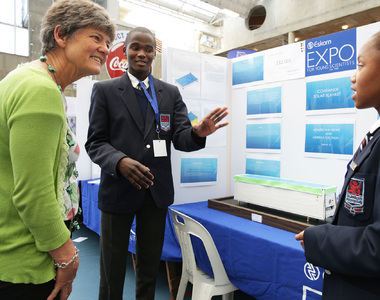

The UCT development is noteworthy as it’s the first certified foundational course in Khoekhoegowab to be offered by a South African higher education institution, explained Dr June Bam-Hutchison. Dr Bam-Hutchison is the interim director of the new Khoi and San Research Unit in UCT’s Centre for African Studies (CAS).

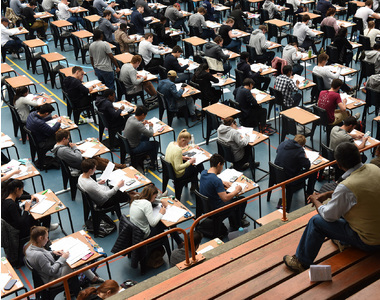

Van Sitters, who is the course convenor, has taught Khoekhoegowab at community level for many years. UCT’s new offering has been well received, he said, with an initial enrolment of 52 participants; the youngest 18 years old and the oldest aged 60. Thirty-seven enrollees completed the programme at the end of November 2020.

The Khoekhoegowab teaching partnership is a collaboration between CAS, the A/Xarra Restorative Justice Forum at CAS, and the Development and Alumni Department (DAD) through the former Centre for Extra-Mural Studies, which is now part of DAD. This three-way partnership also underpins the Khoekhoegowab Curriculum Review Committee.

Socially appropriate teaching

“This committee serves as a sounding board on teaching pedagogy as the socially appropriate teaching of Khoekhoegowab involves the wider context of heritage and history in the Western Cape,” said Bam-Hutchison. “Bradley’s vast knowledge and experience through his language activism have been great assets in convening an appropriate course located within the everyday realities of the Cape Flats and other communities.”

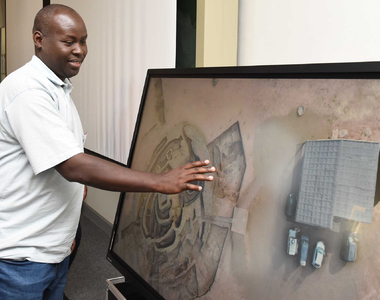

The online version of the course has been facilitated by the development of an extended language toolkit consisting of weekly lesson plans using PowerPoint presentations and videos. The team also used indigenous folktales from the Stories op die wind collection, and songs from the Khoekhoegowab Concert Songbook.

There has been a marked interest in the online course from first-language Khoekhoegowab speakers in Namibia, who are keen to improve their reading and writing proficiency as they haven’t been formally taught in their mother tongue, said Van Sitters.

The Curriculum Review Committee now plans to roll out intermediate courses more suited to their proficiency levels, in partnership with Khoekhoegowab First Language teachers, when there are resources and teaching capacity to do so.

Digital challenges

In developing the Khoekhoegowab online course, the organisers drew on UCT’s blended teaching-and-learning model, which evolved over the past nine months because of COVID-19.

But the digitised terrain presents “immense challenges” in a social distancing teaching context, said Bam-Hutchison. Many of the community-based participants live in remote regions with limited data and technology at their disposal.

To counter this, each participant received the Basic Foundation of Khoekhoegowab course manual and a SIM card with 5 GB of data. But an induction into Microsoft Teams was initially required as online learning was uncharted territory for most.

Thankfully, UCT’s Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching (CILT) rallied to assist, she said. With technical help from Information and Communication Technology Services’ Laz Taho and “immense” administrative assistance from DAD’s Arlene Bowers, the process was smoothed considerably. Those who were unable to participate in this online intake have been placed on the waiting list for face-to-face tuition in 2021.

The Curriculum Review Committee also met weekly with Van Sitters to review and improve the course, based on students’ feedback.

New audiences

But Van Sitters is excited by the potential of online teaching to revitalise the language in previously inaccessible areas and to reach new audiences. The online course has attracted interest from Germany, Portugal, Turkey and Somalia, as well as from an African working in New York.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic compelled our language offering to shift towards online blended learning, it inadvertently broadened the programmeʼs reach and target market,” he said.

The process of developing the online course has been revealing in other areas, he noted.

“The desired outcomes for ancestral language instruction are very different from teaching foreign languages. Many participants want to reconnect with their ancestry through the language acquisition process. Others wanted to learn about the epistemology of Khoekhoegowab words linked to memory.”

“This language is well beyond the stage of mere endangerment.”

Van Sitters added: “Within a decolonial pedagogy we included additional readings to deepen the engagement process whereby language is a means of unlocking indigenous knowledge and cosmologies. As the course convenor, I realised that this work is a pioneering process involving the expansion of new models of language education within indigenous knowledge terms of reference.”

This work is urgent, lest Khoekhoegowab face linguicide, he said.

“This language is well beyond the stage of mere endangerment … and serious efforts are required to develop Khoekhoegowab and raise its status, making the work of the Khoi and San Centre pivotal to training new speakers and language practitioners.”

Partnerships

The programme also underpins a current southern African indigenous languages research project with colleagues in [the Department of] Linguistics who are working with the unit, said Bam-Hutchison.

“However, the huge costs of data and technical support in a COVID-19 context are a significant challenge, and the unit hopes to attract more funding to sustain this important project for the community.”

“Universities now have to develop capacities for marginalised African languages, including Khoi and San languages.”

She said that multilingualism in African languages remains a challenge to UCT’s transformation and decolonisation project. But the new national Language Policy Framework of 2020 has made it a legislative imperative.

“Universities now have to develop capacities for marginalised African languages, including Khoi and San languages,” Bam-Hutchison added. “Going forward, this work is very significant to the Khoi and San Centre. Foundational certification is important because that is where a language is restored in the everyday over the long term.”

To develop beyond foundational Khoekhoegowab, the Khoi and San Centre will explore and establish further teaching and learning partnerships with their Language Development Education colleagues at UCT, and colleagues in African Languages and Linguistics.

When she spoke at the opening of the Khoi and San Centre earlier this year, Vice-Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng said that its establishment was in step with UCT’s new institutional strategy, Vision 2030. Transformation formed its core.

“Vision 2030 challenges UCT’s colonial and apartheid history by affirming UCT’s African identity, reclaiming African agency and committing to the future of the continent as a global African university.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.