UCT scholar ignites Sesotho science revolution

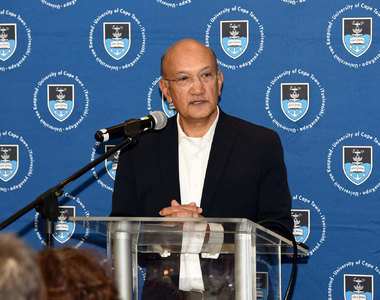

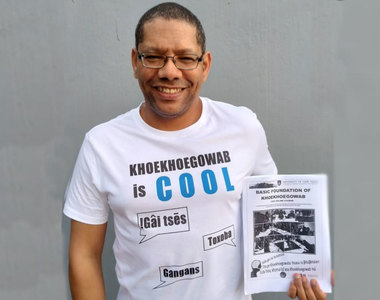

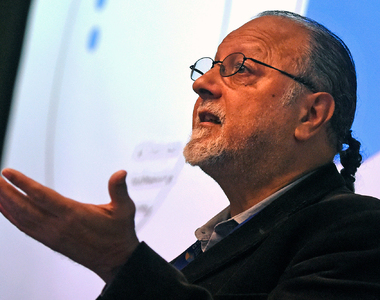

11 December 2025 | Story Myolisi Gophe. Photo Lerato Maduna.

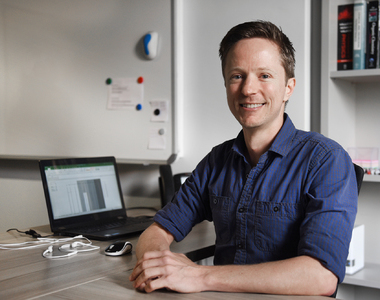

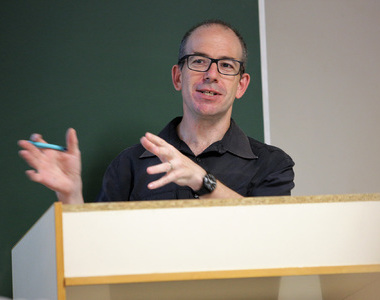

In a bold stride toward decolonising knowledge production in South Africa and beyond, University of Cape Town (UCT) academic Associate Professor Rethabile Possa has authored what is believed to be the first full scientific book series written entirely in Sesotho.

The groundbreaking two-volume work – peer-reviewed, fully scientific, and already influencing continental debates – marks a significant moment in African scholarship and language justice.

But behind this achievement lies a story of vision, resistance, and unshakable commitment to restoring African languages to the centre of academic research.

Associate Professor Possa, who heads the African Languages and Literature section in UCT’s Faculty of Humanities, is also a staff assessor, a gender-based violence tribunal staff assessor, a registration advisor, and the current warden of Fuller Hall residence. She is also the assistant warden at Forest Hill Residence. Nationally, Possa chairs the Sesotho National Language Body under the Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB), and internationally, she serves as the principal examiner for the International Baccalaureate (IB). Even with these many responsibilities, she has found the time – and courage – to lead a project she describes as “long overdue for African scholarship”.

“We need to come up with our own theories,” she said. “As Africans, we have indigenous knowledge systems, philosophies, and practices that are completely different from English frameworks. We’ve been copying English for too long. None of those theories speaks to our ubuntu; to our lived experiences.”

This realisation led her to develop a proposal centred around creating original African theoretical frameworks written in Sesotho by Sesotho speakers, for Sesotho-speaking communities, learners, and researchers.

Partnering with a colleague in the Faculty of Health Sciences, Dr Matumo Ramafikeng, she submitted a funding proposal to the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS). The vision was ambitious: to gather experts from Lesotho, South Africa, Eswatini, and Zimbabwe to produce original, peer-reviewed research written exclusively in Sesotho.

The NIHSS embraced the novelty of the project and provided seed funding. “They did not fully understand the scale of what we were trying to achieve,” she reflected, “but they supported us enough to get started.”

Building African knowledge in African languages

The project quickly grew beyond expectations. Workshops were held in South Africa and Lesotho to come up with concepts, harmonise terminology, and develop approaches for writing academic research in Sesotho, something that had never been systematically done before.

The chapters that emerged were interdisciplinary and deeply rooted in African experiences. They covered:

“I expected one volume,” she said. “But the response was overwhelming. I received so many chapters from Lesotho, South Africa, and Eswatini that I had to split them into two full volumes.”

Both volumes underwent rigorous internal and external peer review through the Centre for Advanced Studies of African Society (CASAS), the University of the Western Cape-based publisher specialising in African languages and orthographic harmonisation.

The first volume was launched earlier this year; the second is scheduled to be printed in January 2026.

Because of Possa’s national role in the PanSALB Sesotho National Language Body, the terminology has now been officially authenticated and standardised. This means it can be nationally distributed and used in schools, universities, and research institutions.

She also created a standard research template entirely in Sesotho, guiding scholars on how to structure academic chapters, abstracts, methodology and analysis.

“This project had to start with agreeing on terminology,” she explained. “Without shared vocabulary, you cannot build a body of scientific knowledge in an African language.”

Embracing two orthographies

A key challenge was that Sesotho is written in two different orthographies: the South African one, which follows the International Phonetic Alphabet system; and the Lesotho one, which bears French missionary influence.

Rather than allow this difference to divide contributors, Possa chose to include both.

“I refused to open the can of worms around orthography politics,” she said. “All I want is research. All I want is for us to start somewhere.”

CASAS initially resisted the idea of publishing a book series containing both orthographies – something no publisher had previously attempted.

But the scholarly merit of the work persuaded them to reconsider.

“This book now opens the door to harmonisation debates,” she added. “Lesotho cannot say they won’t use it. South Africa cannot say they won’t use it. Both orthographies are represented, which is a strength, not a weakness.”

Despite the project’s groundbreaking nature, Possa’s journey highlighted the broader challenges faced by scholars working in African languages within traditionally English-dominant academic spaces.

“The challenge was that my work was not in English,” she said. “Therefore, it was not seen as worthy of recognition.”

“If the work is used in Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia – that is international,” she argued. “African languages are not inferior.”

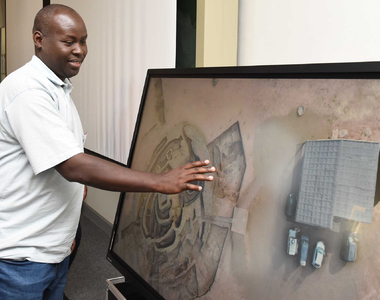

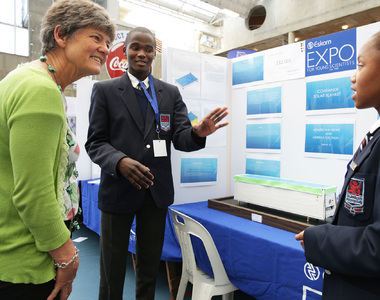

While local recognition was limited, institutions elsewhere welcomed the project with open arms. The book was launched at the Central University of Technology in collaboration with the University of the Free State and PanSALB in the Free State, where Sesotho is an official language of teaching and learning. She received invitations to speak about the work on television and at institutions outside UCT.

Her work lays the foundation for a future in which multilingual scholarship is normalised, not exceptional. For a new generation of African researchers, she is opening doors that have long been closed.

“We must start somewhere,” she said. “This project is that beginning.”

The groundbreaking two-volume work – peer-reviewed, fully scientific, and already influencing continental debates – marks a significant moment in African scholarship and language justice.

But behind this achievement lies a story of vision, resistance, and unshakable commitment to restoring African languages to the centre of academic research.

Associate Professor Possa, who heads the African Languages and Literature section in UCT’s Faculty of Humanities, is also a staff assessor, a gender-based violence tribunal staff assessor, a registration advisor, and the current warden of Fuller Hall residence. She is also the assistant warden at Forest Hill Residence. Nationally, Possa chairs the Sesotho National Language Body under the Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB), and internationally, she serves as the principal examiner for the International Baccalaureate (IB). Even with these many responsibilities, she has found the time – and courage – to lead a project she describes as “long overdue for African scholarship”.

The seed for the project was planted in 2019. It took root during the COVID-19 lockdown, when Possa began reflecting deeply on the limitations of relying exclusively on Eurocentric theories and English-only research outputs.“As Africans, we have indigenous knowledge systems, philosophies, and practices that are completely different from English frameworks.”

“We need to come up with our own theories,” she said. “As Africans, we have indigenous knowledge systems, philosophies, and practices that are completely different from English frameworks. We’ve been copying English for too long. None of those theories speaks to our ubuntu; to our lived experiences.”

This realisation led her to develop a proposal centred around creating original African theoretical frameworks written in Sesotho by Sesotho speakers, for Sesotho-speaking communities, learners, and researchers.

Partnering with a colleague in the Faculty of Health Sciences, Dr Matumo Ramafikeng, she submitted a funding proposal to the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS). The vision was ambitious: to gather experts from Lesotho, South Africa, Eswatini, and Zimbabwe to produce original, peer-reviewed research written exclusively in Sesotho.

The NIHSS embraced the novelty of the project and provided seed funding. “They did not fully understand the scale of what we were trying to achieve,” she reflected, “but they supported us enough to get started.”

Building African knowledge in African languages

The project quickly grew beyond expectations. Workshops were held in South Africa and Lesotho to come up with concepts, harmonise terminology, and develop approaches for writing academic research in Sesotho, something that had never been systematically done before.

The chapters that emerged were interdisciplinary and deeply rooted in African experiences. They covered:

- misdiagnosis and health communication barriers caused by mistranslation

- theatre studies and African performance traditions

- indigenous knowledge systems and folklore

- the role of interpreters in the justice system and how inaccurate translation often leads to wrongful arrests

- pedagogies for teaching Sesotho poetry, addressing challenges faced by new teachers

- disability inclusion and the need for specialised linguistic approaches

- vocabulary development for research and scientific terminology in Sesotho.

“I expected one volume,” she said. “But the response was overwhelming. I received so many chapters from Lesotho, South Africa, and Eswatini that I had to split them into two full volumes.”

Both volumes underwent rigorous internal and external peer review through the Centre for Advanced Studies of African Society (CASAS), the University of the Western Cape-based publisher specialising in African languages and orthographic harmonisation.

The first volume was launched earlier this year; the second is scheduled to be printed in January 2026.

One of the most significant outcomes of the project is a newly developed, standardised terminology list for research concepts in Sesotho – a necessity for future scholars who wish to write theses, dissertations and scientific texts in the language.“The challenge was that my work was not in English. Therefore, it was not seen as worthy of recognition.”

Because of Possa’s national role in the PanSALB Sesotho National Language Body, the terminology has now been officially authenticated and standardised. This means it can be nationally distributed and used in schools, universities, and research institutions.

She also created a standard research template entirely in Sesotho, guiding scholars on how to structure academic chapters, abstracts, methodology and analysis.

“This project had to start with agreeing on terminology,” she explained. “Without shared vocabulary, you cannot build a body of scientific knowledge in an African language.”

Embracing two orthographies

A key challenge was that Sesotho is written in two different orthographies: the South African one, which follows the International Phonetic Alphabet system; and the Lesotho one, which bears French missionary influence.

Rather than allow this difference to divide contributors, Possa chose to include both.

“I refused to open the can of worms around orthography politics,” she said. “All I want is research. All I want is for us to start somewhere.”

CASAS initially resisted the idea of publishing a book series containing both orthographies – something no publisher had previously attempted.

But the scholarly merit of the work persuaded them to reconsider.

“This book now opens the door to harmonisation debates,” she added. “Lesotho cannot say they won’t use it. South Africa cannot say they won’t use it. Both orthographies are represented, which is a strength, not a weakness.”

Despite the project’s groundbreaking nature, Possa’s journey highlighted the broader challenges faced by scholars working in African languages within traditionally English-dominant academic spaces.

“The challenge was that my work was not in English,” she said. “Therefore, it was not seen as worthy of recognition.”

She faced pressure to translate the work into English and was told that Sesotho research would not be recognised internationally. But her definition of “international” was different.“African languages are not inferior.”

“If the work is used in Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia – that is international,” she argued. “African languages are not inferior.”

While local recognition was limited, institutions elsewhere welcomed the project with open arms. The book was launched at the Central University of Technology in collaboration with the University of the Free State and PanSALB in the Free State, where Sesotho is an official language of teaching and learning. She received invitations to speak about the work on television and at institutions outside UCT.

Her work lays the foundation for a future in which multilingual scholarship is normalised, not exceptional. For a new generation of African researchers, she is opening doors that have long been closed.

“We must start somewhere,” she said. “This project is that beginning.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.