Toilet flushing guidelines during drought

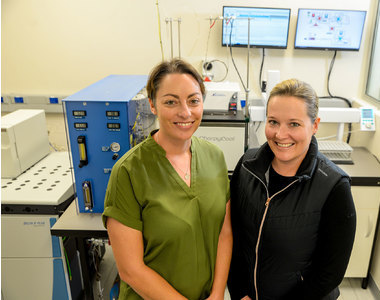

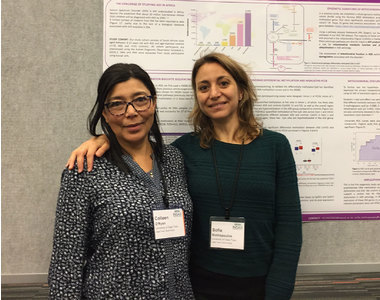

08 July 2019 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Candice Lowin. Read time 7 min.

Using grey water to flush toilets saves water but solid build-up could harm the pipes, especially during times of drought when householders flush less often.

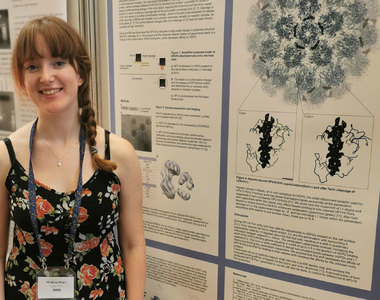

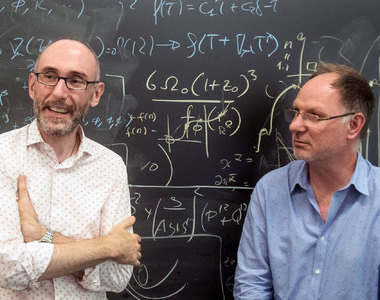

A new paper in the Journal of Water Process Engineering by University of Cape Town (UCT) researchers Waseefa Ebrahim and Dr Dyllon Randall offers some practical solutions for water savers to avoid damaging their sanitation infrastructure.

These guidelines are applicable for water-conscious Capetonians who flush with grey water from handwashing (tap water with soap) or from showering (tap water with soap and shampoo).

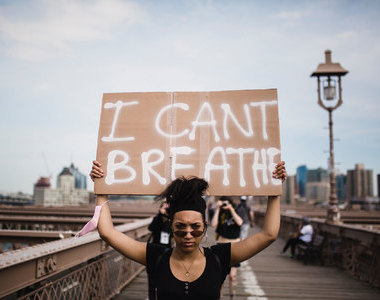

The paper is in response to the devastating 2015–2018 drought and its aftermath when citizens got behind city-wide water savings initiatives and adopted the catchphrase “If it’s yellow let it mellow”, flushing less and using grey water to do so.

The result was a more than 50% reduction in water usage compared with pre-drought conditions. Water demand dropped from 1 200 ML a day in February 2015 to 500 ML a day in February 2018, a significant achievement for a city of 4.1 million people, said the authors.

“But the immediate toilet infrastructure, such as the trap, siphon and piping connection to the sewer network, could become clogged.”

Ebrahim and Randall calculated that the city’s waste-water treatment plants could cope with the additional estimated 893 tons of solids added to the system from grey-water flushing and allowing urine to stagnate in toilet bowls.

But the immediate toilet infrastructure, such as the trap, siphon and piping connection to the sewer network, could become clogged by solids because of precipitation during reduced flushing periods.

Lab tests

In their lab tests they used cleaning products typically found in South African households to provide a realistic product representation for the synthetic grey water, and included soap, shampoo, vinegar and bleach. By testing the solutions before and after flushing, they recorded the most significant compositional changes for analysis.

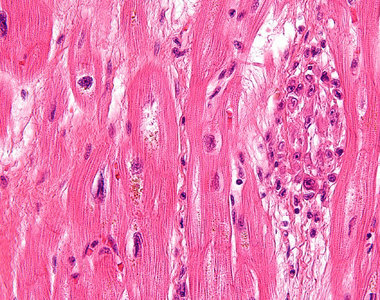

They found that some solids that had formed during their experiments could not be removed from equipment simply by rinsing with water. Instead, equipment had to be cleaned using a weak acid solution.

“This suggests that solids could serve as nuclei on which new solids grow,” they noted.

“This could lead to solid build-up in the pipes, reducing their capacity and lifespan.”

The key parameter that influences the build-up of solids is the pH of the solution, said Randall. Conventionally, flushing a toilet bowl with tap water after each toilet use will decrease the pH and thus limit solid build-up.

“However, limited toilet flushing and flushing with grey water, which inherently has a high pH, will increase the pH of the solution. It is this increase in solution pH that results in solid formation from the stagnating urine.”

Ebrahim and Randall found that the maximum pH of the solution in the toilet bowl was reached in just two days when using grey water to flush, which resulted in excessive solid formation.

They say further research is urgent if costly piping and infrastructure replacement is to be avoided.

Guidelines for water savers

In their paper, the researchers have listed five recommendations:

- Flush the toilet with grey water but add bleach to the toilet bowl after the manual flush. This will kill any bacteria in the toilet bowl, and thus limit solid build-up. Adding bleach after a grey-water flush also means that the bleach is not being added to a concentrated ammonium solution such as stagnated urine, thus avoiding harmful gases forming.

- Don’t allow grey water to stagnate for more than two days because this can promote bacterial growth and malodours.

- Don’t flush with grey water for longer than two days without also disinfecting the toilet bowl with bleach.

- Don’t add bleach to stagnated urine because of the potential harmful gases that can form. Instead, follow the first step.

- Adding vinegar to a toilet bowl will reduce the pH of the solution and hence prevent solid build-up, but the acetate in the vinegar will promote bacterial growth. The researchers therefore recommend that vinegar not be added unless bleach is also added.

Randall, who is also part of UCT’s Future Water Institute, hopes that future households will have waterless urinals, also designed to recover nutrients from urine.

“This would limit issues associated with stagnating urine in toilet bowls during times of reduced toilet flushing while also saving water and recovering valuable resources.”

He added: “The social acceptance and technical feasibility at a household level would have to also be assessed though for this method to be adopted.”

Looking ahead, Ebrahim said society is moving towards closing the loop on the water cycle by reusing grey water and reducing waste in general.

“It [this work] was inspired by the Cape Town [water] crisis but ultimately we’re looking towards what the sanitation of the future will look like.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.