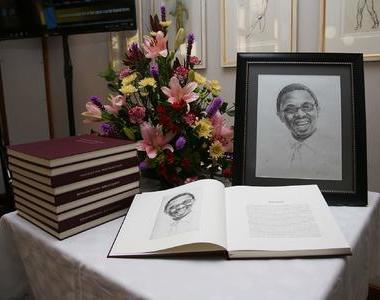

‘You make peace with pain’

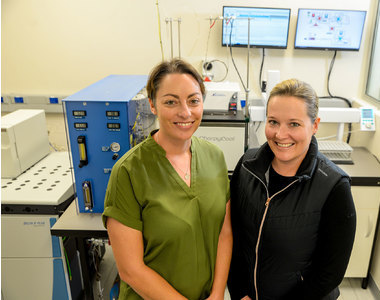

23 March 2021 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Je’nine May. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 10 min.

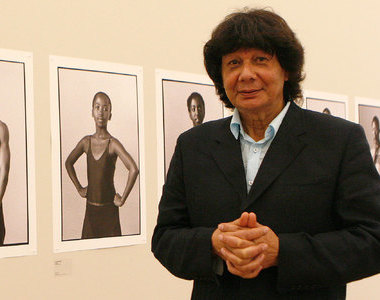

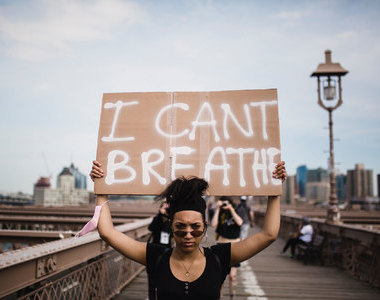

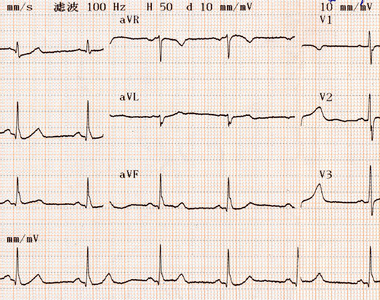

In intensive care with severe COVID-19 and double pneumonia, University of Cape Town (UCT) academic Gao Nodoba sensed patients on one side of his cubicle had died. The curtains were drawn and all was quiet. For the first time during his marathon 20 days in the intensive care unit (ICU), when his blood oxygen levels dropped to 30%, he was afraid.

He knew he had to fight. People were relying on him. His seesawing physical and emotional state became a battle in the mind. But mental strength and the will to live sustained him.

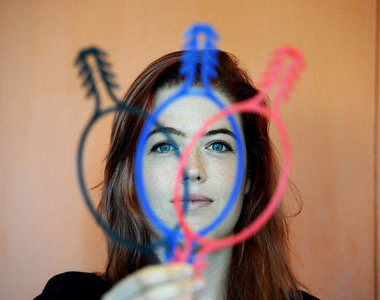

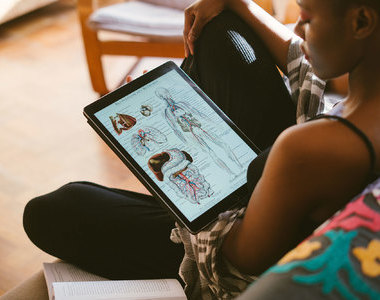

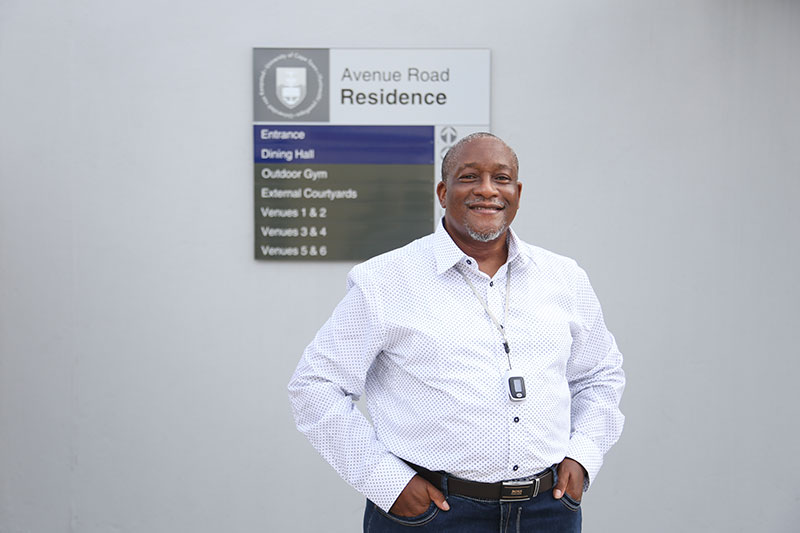

Since his discharge from hospital on 26 January, Nodoba (56) now has two trusty companions. The pulse oximeter slips over his finger and measures his blood oxygen saturation levels. The spirometer measures his breathing efficiency.

In a virtual interview about his experiences, a year after the country’s mandatory lockdown began, Nodoba demonstrated how these companions work.

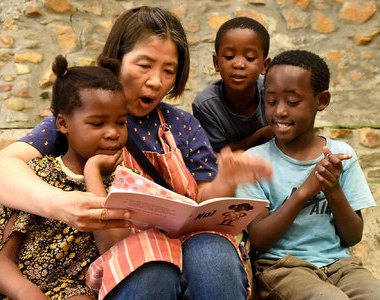

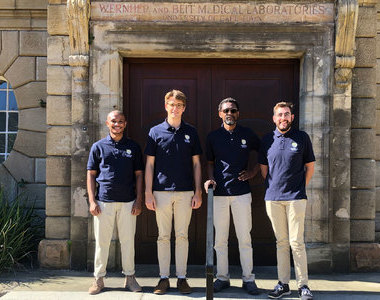

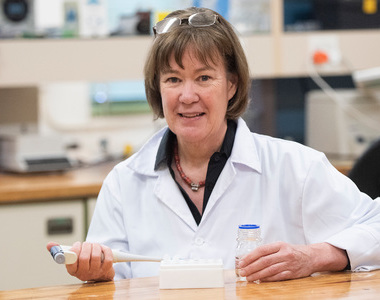

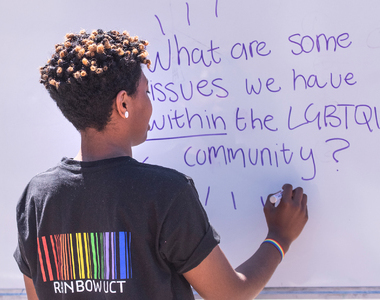

They reassure him that all is well, said Nodoba, who teaches business communication, corporate communication, intercultural communication and diversity management on the Professional Communication Unit’s postgraduate diploma in business communication in the School of Management Studies. He is also a warden at two residences, University House and the new Avenue Road Residence, both in Mowbray.

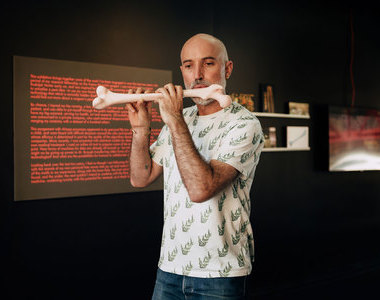

“See?” he said, holding up the spirometer. He exhaled into the tube and the red ball shimmied upwards, butting the plastic top. “See how high it goes?”

Slipping the oximeter onto his finger, he watched the screen. Fixedly. “Right, my reading is 96%, above the threshold of 90%. So, Iʼm okay; normal.”

Life and death

Two months ago Nodoba couldn’t do that. He battled to breathe; his blood saturation levels plummeted to 30% as he teetered between life and death in the ICU at Life Vincent Pallotti Hospital.

COVID-19 came like the proverbial thief in the night. It was the end of December; one day he was fine, the next tired, peaky. His wife, Bulelwa (she is dubbed “Saint Bulelwa” in this interview), nudged him to see the doctor.

“You know, women can be very diplomatic, while we men can be stubborn,” he said, playfully.

It was only when their doctor took an oximeter reading that the alarm bells sounded.

“This instrument is what saved me while we were waiting for the [COVID-19] test results,” Nodoba said, wagging the oximeter on the tip of his finger. He was hospitalised and given high-flow additional oxygen to stabilise his condition.

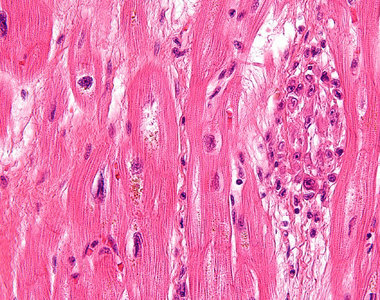

“I had two devils to deal with: COVID-19 and COVID-19 double pneumonia.”

The positive diagnosis was a shock. Following the university’s closure in mid-March last year, campus had been almost deserted. Residences too. He had worn his mask and sanitised … Bulelwa tested negative – twice.

His descent was terrifyingly fast.

“I had two devils to deal with: COVID-19 and COVID-19 double pneumonia. And it hit me so hard that my oxygen levels went down tremendously. My two admitting doctors decided I should be taken to ICU. I was already breathing with oxygen support.”

The move to intensive care left him and his family distraught. As his oxygen levels continued to fall, fatigue and joint pain escalated. He was experiencing profound discomfort.

Switching to fight mode

“It was as if my body was being cut all over at the same time,” he said. And the headaches were severe. “You could take Panado until the cows came home. Nothing helped.” He became incapacitated, unable to visit the bathroom or wash himself.

“I realised I needed to fight this thing. If you don’t shut out the pain, it will kill you. You have to use the power of your mind.”

Nodoba also needed people who would fight for and with him. The former were his family: Bulelwa and their two children, Nikita and Modisaemang. Committed Christians, they fasted, prayed and rallied the couple’s family and church community to do the same. Bulelwa’s energy and faith in his ability to recover buoyed him. Her daily scripture messages of encouragement were a balm. She sent voice notes, and gospel songs with refrains that stuck – and were replayed. Soon, he was “swimming in positivity”.

“I told myself that Iʼve got a powerful testimony to share, and I want to be an ambassador … I want to say to people with family in ICU: It’s not a deathbed.”

“I would wake up [at] five oʼclock and ask the nurses to put on the headphones for me and I would play that music. And it gave me hope.” Bulelwa also became the communications hub for a wider circle – family, friends and colleagues – to conserve his energy and minimise distress.

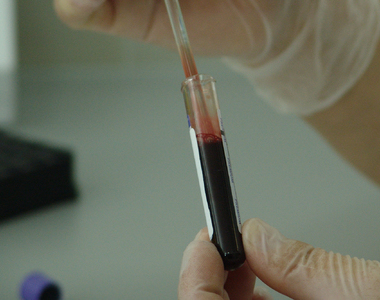

The second group of “fighters” were the “amazing” medical staff at the hospital, including the four ICU doctors dedicated to his care. They were doing everything to keep him alive; inducing deep sleep, turning him to lie in the prone position to facilitate recovery, medicating him, testing his blood samples every three hours, checking for infections and effects on his organs – and constantly monitoring his oxygen levels.

Nodoba also took heart from the medical team. One of the ICU nurses had recovered from COVID-19 but was back in the ward – where she was needed, he said. He took courage from that. Later, other staff gravitated to him and his positivity. Once, 10 nurses gathered at his bedside to hear his prayer for them.

“A revival!”

He added: “I told myself that Iʼve got a powerful testimony to share, and I want to be an ambassador … I want to say to people with family in ICU: It’s not a deathbed. God can use you in any situation to become a blessing to others … And the staff go beyond the call of duty. Those four doctors in ICU, the nurses, my two admitting doctors, those physiotherapists … those people are angelic. What unsung heroes! Can this country please take its healthcare practitioners seriously?”

Despair and humour

Nodoba doesn’t avoid talking about moments of despair: Two patients to one side of him died. He was convinced it was only a matter of time before he left ICU in a body bag.

“I cried myself to sleep that night. Fortunately, by God’s grace, I did not get a ventilator. But I was a candidate.”

There were also comic moments when his befuddled mind played tricks on him.

“I might be laughing now, but this is not a joke,” he said, recalling being woken by the medical staff after an induced deep sleep.

“COVID-19 is something that I donʼt wish on any human being, [not] even my worst enemy.”

“I saw all these people in white around my bed. What came to me immediately was: angels! I went hysterical. I shouted, ‘God Iʼm not ready! Please donʼt take me, please!’ It took them an hour to calm me down. You see, I couldnʼt tell my wife what was happening. I wasn’t ready to die.”

He did reach a point of no return when the doctors and staff had done all they could, and it was up to him to fight.

“That was the defining moment. That was the scariest time while I was in ICU. The tears just dropped down.” He paused. “COVID-19 is not something you play with. Please give this message to anyone tired of wearing a mask, sanitising, missing out on gatherings and social events.

“COVID-19 is something that I donʼt wish on any human being, [not] even my worst enemy. Itʼs a cruel violence. Itʼs devastating. Itʼs awful. And it makes you to feel life is worthless.”

By then he’d lost weight and muscle mass after weeks of immobility. A team of physiotherapists worked to rehabilitate him and, said Nodoba, he was ashamed that he couldn’t get into a chair unassisted. He couldn’t blow his nose.

“And I asked myself: What value am I to society? If I die, what will happen to my wife, my children, my extended family and those that depend on me? What will happen to my colleagues? And the students that I need to supervise? And our good [academic] projects?”

“To the people out there, this virus is deadly. I was given a second chance in life; a second lease.”

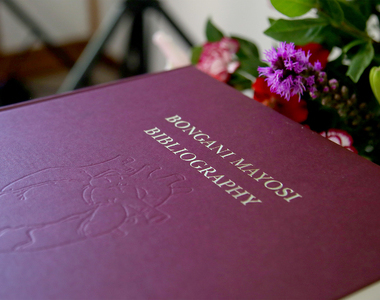

Last year Nodoba and a colleague developed a new massive open online course with GetSmarter/2U, Communication and Influence in the Digital Age.

“It started on 25 January and I was thinking about this new baby. I wanted to see its impact in the corporate world.”

Aftermath and a message

Having recovered and returned to work, Nodoba is on a crusade about COVID-19.

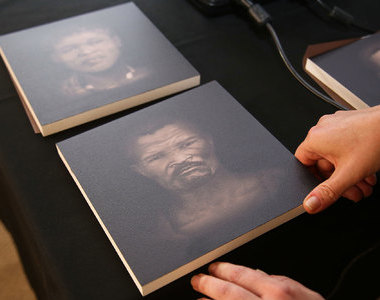

“I think I’m going to write a book on this thing. I might call it ‘The Loneliness of the COVID-19 sufferer’. It’s like the loneliness of the long-distance runner. There comes a time when you are on your own.”

To end, he had a terse message for those in power – the president, the minister of health and the province’s premier: “Can politicians please stop playing games? Can people stop stealing money that is meant to save lives?

“And to the people out there, this virus is deadly. I was given a second chance in life; a second lease.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.