Vaccinations, regular screening key to eliminating HPV

08 April 2022 | Story Niémah Davids. Photo Pexels. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 7 min.

Fast-tracking access to vaccines for cervical human papilloma virus (HPV) is of utmost importance to reduce the burden of infection in sub-Saharan Africa, and will help save thousands of young women’s and girls’ lives.

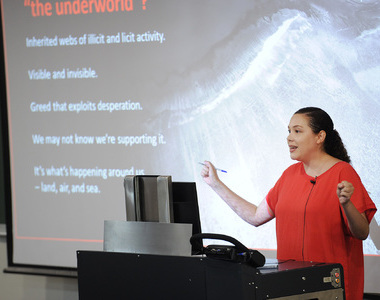

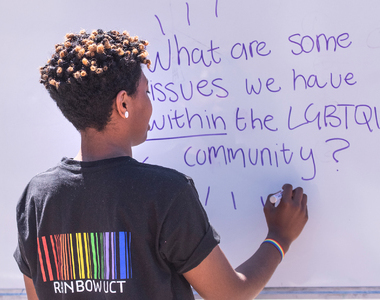

This was one of the recurring messages shared by several speakers during a belated HPV Awareness Day seminar. International HPV Awareness Day is observed annually on 4 March.

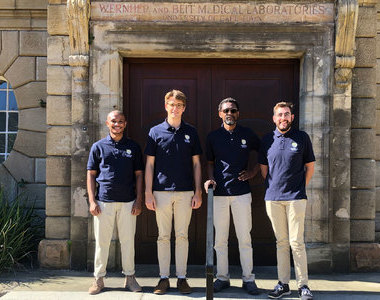

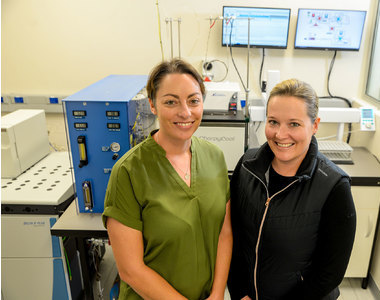

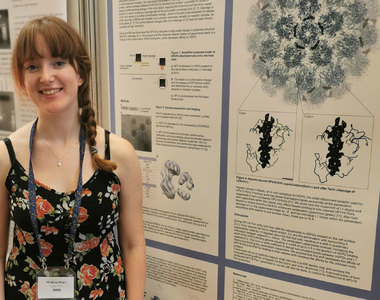

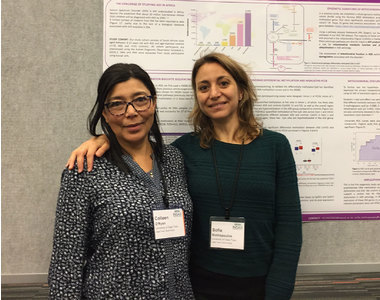

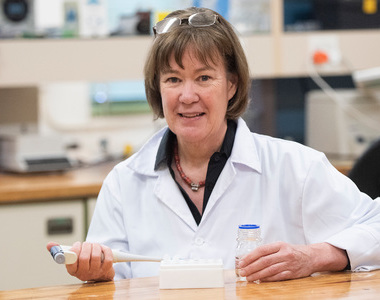

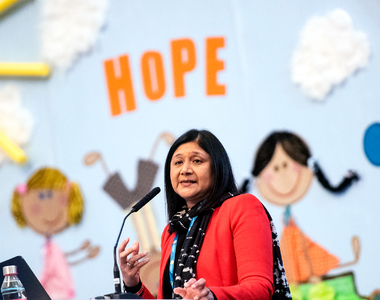

The hybrid event, held on Thursday, 7 April, was organised by the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Gynaecological Cancer Research Centre (GCRC) based in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the Faculty of Health Sciences. The seminar was hosted by Professor Lynette Denny, the director of the GCRC, and aimed to provide the audience with a snapshot on where South Africa finds itself in its fight against HPV.

Unpacking the virus

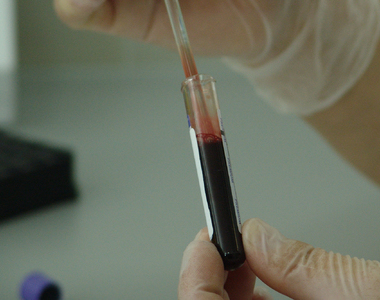

HPV is a common viral infection of the reproductive tract and is spread through skin-to-skin contact. There are more than 100 different types of HPV, which infect the genitals, mouth and throat. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), most HPV infections clear on their own. However, there is a risk that the infection may become persistent and lead to pre-cancerous lesions within in the infected areas. These pre-cancerous lesions may progress and develop into invasive cervical cancer.

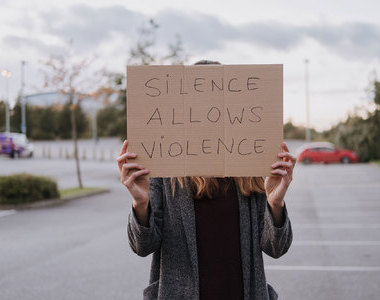

“This [cervical cancer] is very much a disease of inequity, either in terms of access to screening and prevention, and access to early detection and treatment.”

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer globally, and in 2020 claimed the lives of approximately 350000 women. More than 80% of cases occur in low- to middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Melanesia, Asia and Southeast Asia. In South Africa, thousands of cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed every year, and the prognosis is not good.

“This [cervical cancer] is very much a disease of inequity, either in terms of access to screening and prevention, and access to early detection and treatment,” Professor Denny said.

Why it’s important

According to Professor Sinead Delany-Moretlwe, the director of research at the Reproductive Health Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, cervical cancer affects women in the prime of their lives and the mortality rate is highest in sub-Saharan Africa.

Professor Delany-Moretlwe described cervical cancer as “incredibly common”, which causes significant burden of disease. That burden, she explained, is normally felt by people who already experience health disparities like women and girls living in marginalised communities with poor access to healthcare. HIV infection also increases the risk of developing cervical cancer. In fact, women living with HIV are far more at risk of developing HPV compared with HIV-negative women. But not everyone who contracts HPV will develop cervical cancer.

“What we understand from the epidemiology is that HPV acquisition is associated with the onset of sexual activity. Over the course of 12 months, most people will clear their infection, but some may go on to develop persistent infection. And certainly, people who are immunocompromised are more likely to [battle] to clear their infection or [will] take longer to clear their infection,” she said.

Further, she said, the use of tobacco, long-term hormonal contraception, and high parity also promote progression and increase an individual’s risk of developing cervical cancer.

“The reason this is such a tragedy is because in many instances this infection is preventable [particularly] through primary vaccination or through screening.”

“The reason this is such a tragedy is because in many instances this infection is preventable [particularly] through primary vaccination or through screening, [as well as] through antiretroviral access and coverage,” Delany-Moretlwe said.

HPV and HIV

Sharing her sentiments, the WHO’s Dr Shona Dalal said research conducted by the organisation indicates that women living with HIV have a six-fold higher risk of developing cervical cancer when compared with HIV-negative women.

“Women and girls living with HIV have a higher risk of getting HPV and [a] lower chance of curing the infection. [In this case the virus also has] faster progression, lower regression and higher recurrence rates following treatment,” she said.

Dr Dalal reiterated the importance of screening and treatment. She said cervical cancer cases can be substantially reduced if women living with HIV receive their HPV vaccinations and undergo the necessary screening.

With this in mind, the WHO has developed a set of guidelines specifically aimed at women living with HIV in an effort to prevent cervical cancer. This, she explained, includes a screen, triage and treat approach using HPV DNA as a primary screening test, starting this process at the age of 25 years old and implementing a three-to-five-year screening interval. In addition, the guidelines also highlight the importance of retesting women living with HIV for HPV regularly, especially following a positive screening test and after concluding their treatment programmes. All this should take place before patients move back to routine screening intervals, as a result of the alarmingly high recurrence rate.

Vaccination drive

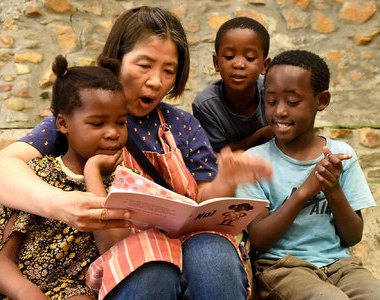

To reduce the high number of cervical cancer among women and girls in the country, government has introduced an HPV vaccination programme in public and special schools. Dr Lesley Bamford, a child health specialist at the National Department of Health (DoH), said the programme is aimed at young girls in Grade 5.

The programme, introduced in 2014 in partnership with the DoH, the Department of Basic Education and the Department of Social Development, forms part of the Integrated Schools Health Programme. It’s delivered in two phases: round one delivers the first vaccine dose in February and March, followed by round two and the second vaccine dose in August and September. The goal, Dr Bamford added, is to reach 80% of public primary schools in the country and 80% of young girls aged nine and above. Girls cannot be vaccinated without a signed parental consent form.

“We are really hopeful and committed to making sure that the programme does continue and that it’s used as a platform for delivering other vaccinations to our learners.”

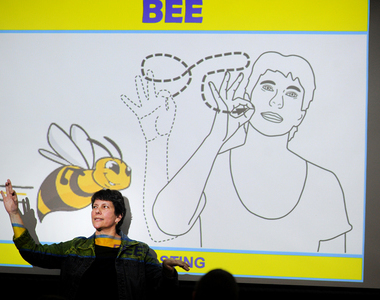

She said the programme would be nowhere without vaccinators, who receive rigorous training to prepare themselves for the job. Their training covers vaccine and cold chain management, vaccine management and administration, and how to monitor adverse events following immunisation. Every year the department aims to vaccinate between 450 000 and 480 000 girl learners, and to date, vaccinators have managed to immunise approximately 80 to 95% of these young girls with a single vaccine dose.

“This programme has had a high level of commitment from the DoH and the Department of Basic Education (and has received) support from civil society, parents and school governing bodies … We are really hopeful and committed to making sure that the programme does continue and that it’s used as a platform for delivering other vaccinations to our learners,” Bamford said.

Other academics who contributed to this discussion included UCT’s Dr Tracey Adams and Dr Rakiya Saidu, and Columbia University’s Dr Louise Kuhn.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.