Restoring dignity through forensic art

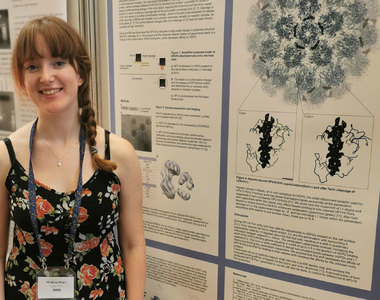

04 November 2019 | Story Nadia Krige. Photos Michael Hammond. Read time 8 min.Growing up in an era when television shows like MacGyver and Police File were at the height of their popularity, Kathryn Smith developed a deep-seated fascination with forensic imaging. This unusual interest led her, fortuitously, to a career-defining opportunity.

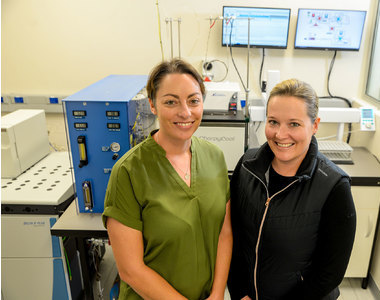

The moment arrived in late 2018 when Dr Victoria Gibbon, senior lecturer in biological anthropology and the curator of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) skeletal collection, approached Smith about the possibility of creating facial reconstructions for eight individuals whose remains had been unethically obtained by the university between 1925 and 1931.

Smith was to become part of a multidisciplinary team of academics who would be contributing to what has come to be known as the Sutherland project, a historically significant process of restitution and reburial initiated by UCT.

Gibbon had come upon the eight skeletons – along with three others – while conducting an archival audit of the Faculty of Health Sciencesʼ skeletal collection in 2017.

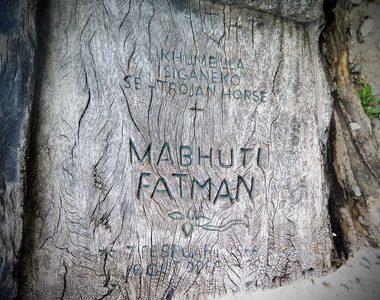

Since nine of the 11 skeletons were San and Khoe people who had come from Sutherland in the Northern Cape, where they had worked as farm labourers, the university decided to start the restitution process there.

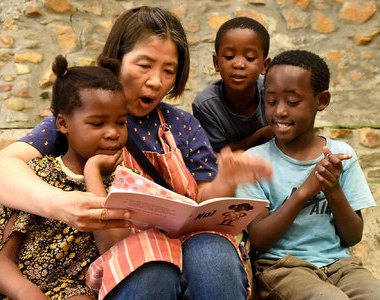

Gibbon visited the Sutherland community to receive input from the Sutherland Abraham and Stuurman families, who had been identified as descendants of at least two of the individuals in question.

The families not only agreed to further research being conducted into the lives and deaths of their ancestors, they also made a specific request for facial reconstructions of the deceased.

“If I had to summarise the ultimate objective, it would be the restoration of personhood.”

Project of a lifetime

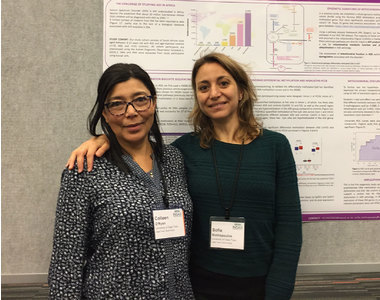

Smith was completing her PhD in forensic art at Face Lab – a research lab at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom – and happened to be in South Africa at the time to conduct fieldwork for her thesis.

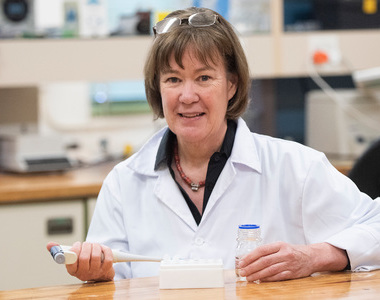

After gaining the approval of Professor Caroline Wilkinson, director of Face Lab and Smith’s PhD supervisor, Smith was quick to join Gibbon’s project team.

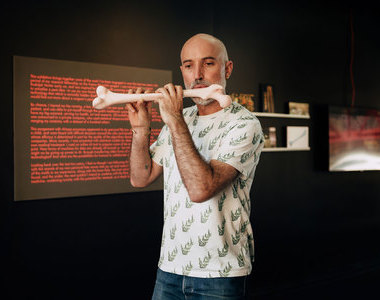

Already well established as one of South Africa’s most prolific young artists and curators, Smith – who is also a senior lecturer in visual arts at Stellenbosch University – recognised the Sutherland project as an opportunity to define herself as an expert in facial reconstruction, a relatively understudied field in South Africa.

“For me, there is nothing that is not exceptional about this project,” she said.

“When I was invited onto it, I just thought ‘I’ve been waiting for this moment’. And I was really hoping that it would happen in my lifetime.”

In pursuit of accuracy

While facial reconstruction of the deceased holds potential for controversy at the best of times, the task requires even more sensitivity when working with individuals who had once moved on the margins of society.

Bearing this in mind, Smith went to great lengths to work with an extra measure of sensitivity and authenticity.

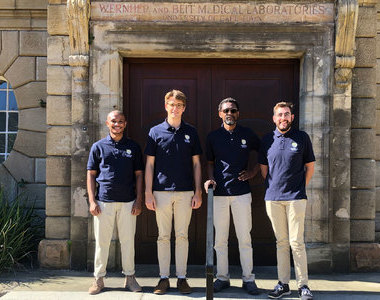

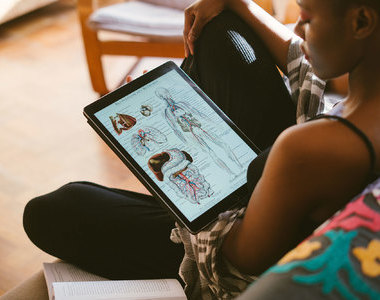

The first step was to acquire computed tomography (CT) scans of the remains. These were produced by Dr Tinashe Mutsvangwa, an expert in the development of advanced medical imaging and analysis from UCT’s Division of Biomedical Engineering.

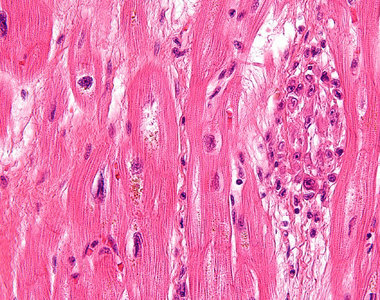

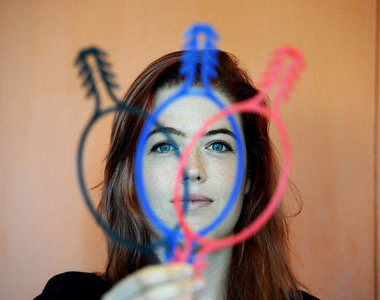

Once received, they were imported into Face Lab’s 3D computer system, where the digital modelling process would begin. This 3D system has a premodelled database of muscles and other anatomical structures that can be imported for each individual skull, and fit to its particular dimensions.

The key, unique feature of this “virtual sculpture” system is the haptic interface, which allows the practitioner to feel the shapes she is modelling on screen. The touch feedback provides important information about the features of the skull that cannot be determined by visual examination alone.

“We look at skeletal detail around the skull to tell us about facial feature prediction,” Wilkinson explained.

“In that way we can follow these standards for predicting the muscle structure, the facial features and then eventually the overall face shape.”

“We look at skeletal detail around the skull ... for predicting the muscle structure, the facial features and then eventually the overall face shape.”

No assumptions

With this in place, it was time to start considering the details such as eye colour, hair colour and skin colour – what Wilkinson and Smith refer to as “textures”.

This is, of course, where things can get tricky.

“It’s important not to assume too much and we need to be able to justify each choice we make,” Smith said.

In order to do this, she worked closely with Gibbon’s biological reports, which helped to provide a measure of context.

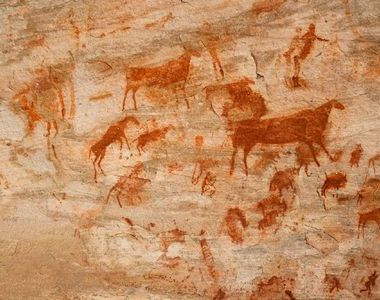

Smith also happened to find an archive of 19th century photographs depicting Khoe and San individuals from the frontier regions of South Africa – including the area around Sutherland – which she used for reference.

As far as accuracy of facial reconstruction is concerned, Wilkinson said that with the increased accessibility of medical imaging over the past 10 to 15 years, it has been possible to test their processes and methodologies on people who are alive.

“That’s enabled us to increase our accuracy by knowing the areas that are weak, and also for us to have an evaluation,” she said.

Personal and public reaction

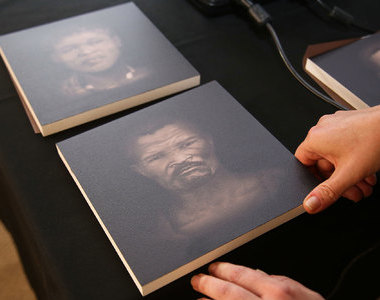

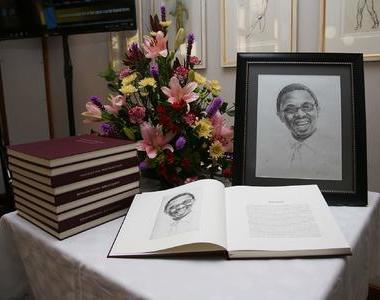

The entire process took Smith a full six months to complete. And the result? Images that are remarkably emotive and almost photorealistic.

They were recently presented to the Sutherland Abraham and Stuurman families, whose response Smith described as being “wholly positive, but with an undercurrent of discomfort”.

“What they said was, ‘We didn’t expect them to look like someone that we could meet in the streets’,” she said.

While she was careful not to ascribe any emotions to the individuals in the images, Smith said she was intrigued by the community’s empathetic reading. Some picked up on an inherent sadness, while others commented on the fact that a couple of them look “’n bietjie kwaai” (a bit stern).

“Since we don’t see many of these types of images being circulated in a South African context, I’m interested to see how the general public will respond,” Smith said.

“I think that’s where the real test lies.”

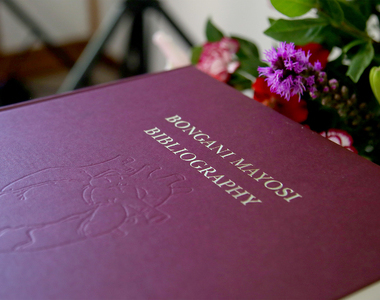

Apart from being a career highlight for her, the Sutherland project was also an invaluable opportunity to play a part in an important process of restitution.

“If I had to summarise the ultimate objective, it would be the restoration of personhood,” Smith concluded.

“Whether in a forensic context or archaeological context, if we have a face and a name – even a face without the name – and this really rich biography that we can reconstruct by virtue of all of these different kinds of expertise, it does contribute to the restoration of dignity.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.