Harnessing community agency

25 March 2021 | Story Thania Gopal. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 9 min.

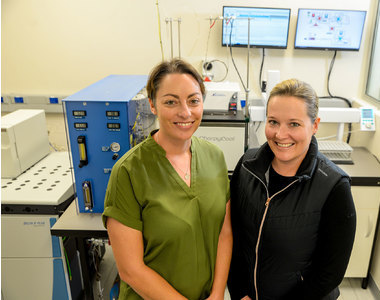

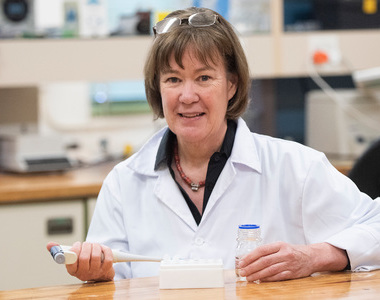

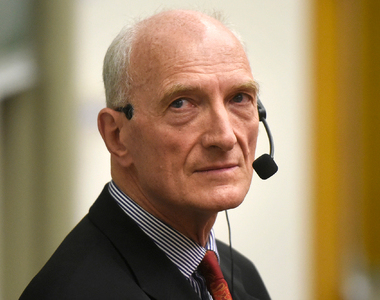

“It is unconscionable that your ability to pay should determine whether you live or die,” said Associate Professor Lydia Cairncross, the head of the Breast and Endocrine Surgery Unit at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Faculty of Health Sciences and Groote Schuur Hospital.

An equitable health system organised on the principles of social solidarity and equality is one in which an unemployed health worker from Khayelitsha would have the same access to quality care (including high care and intensive care) as a chief executive officer of a major conglomeration, Associate Professor Cairncross added.

The COVID-19 pandemic has yet again placed an unrelenting spotlight on the stark inequities in the South African health and social systems. Around 84% of South Africans are dependent on the public healthcare sector with around 16% making use of the private healthcare sector.

“We need one health system to effectively implement a strategy to contain a virus that crosses social boundaries.”

Facing a pandemic with a fragmented and unequal health system will only exacerbate existing inequalities, said Cairncross. “We need one health system to effectively implement a strategy to contain a virus that crosses social boundaries. The public-private divide prevents this.”

In an ideal system, health should be viewed as a public good and access to the health system should be free at the point of service, she said.

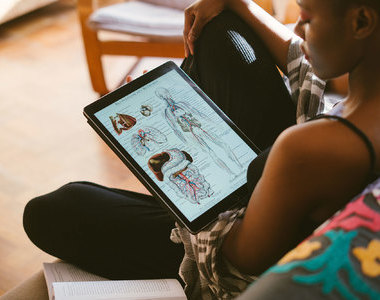

“The health system should be publicly funded and publicly managed and grounded in the principles of primary healthcare, which means that you start off at a community level with community health workers and health promoters as your first connection between the health system and communities. And it means a move away from a purely curative approach to a preventative one.”

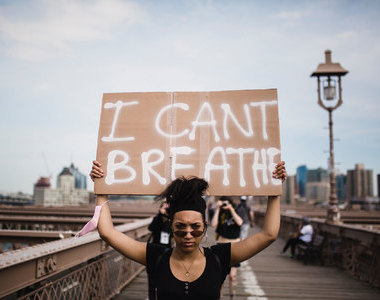

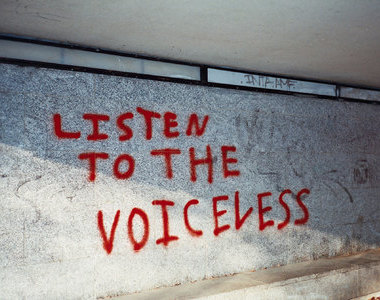

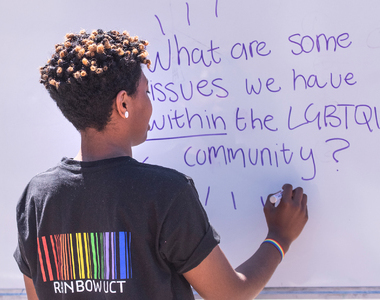

Mobilising communities

Cairncross, a fierce defender of health and human rights, is also a member of the People’s Health Movement of South Africa (PHM-SA). Her advocacy work around the pandemic has been focused on mobilising communities to campaign for a just response to COVID-19.

“COVID-19 has shown us that the link between communities and the health system needs to be strengthened.”

“I think COVID-19 has shown us that the link between communities and the health system needs to be strengthened. To prevent COVID-19 spread, we needed deep and trusted roots in all communities so that the early messages of prevention (and now the message of vaccination) could be delivered quickly and supported effectively,” she said.

“This means having health promoters and community health workers who are recognised, respected and integrated into the health system.”

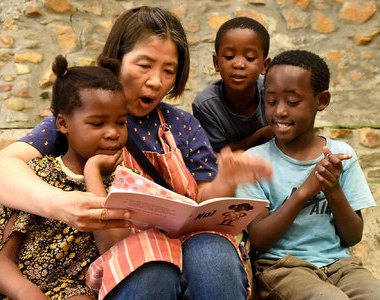

With the support of PHM-SA, Cairncross initiated small-group, face-to-face, COVID-19 training workshops in various communities, including Gugulethu, Khayelitsha, Nyanga, Blikkiesdorp, Tulbagh and Manenberg.

“We wanted to set up the workshops ... to teach communities how to meet safely in the presence of the virus,” she explained.

“We knew that women were still running soup kitchens; children were still being taken care of in groups; neighbourhood watches were still functioning. There were basic community-level meetings that continued and had to continue during lockdown for basic survival.

“You learn about what it means to physically distance when you share a bathroom with two or three other families.”

“And these extensive social networks were what really kept people going during that time, and those community leaders – both official and unofficial – needed to have the knowledge to keep themselves and others safe.”

She also conducted workshops to “train the trainers”, bringing together people from communities who could go on to train others.

Cairncross emphasised that teaching and learning within the community is not one-directional but rather mutually enriching: “It wasnʼt just empowering for community members in the workshops – it was also empowering for us connected to the health system and involved in various kinds of policy conversations, because you learn every time you engage with people who live a different life from yourself,” she said.

“You learn about what it means to physically distance when you share a bathroom with two or three other families, about what it means for families to have children home from school when there is no space for their online learning and only one device in the home, and what it means to have to decide between buying sanitiser and masks and buying food.”

Engaged citizenry

Cairncross believes that more people should engage with “the stark reality of the South Africa we live in” as this will generate a deeper and more nuanced understanding of why people behave in a certain way.

“We have an extremely active engaged citizenry. People are intelligent and innovative and creative. So, if theyʼre not doing the things that public health officials think they should be doing, thereʼs probably a good reason. And if we donʼt understand what those reasons are, weʼre not going to get through this pandemic safely.”

“If we donʼt have housing, water, education [and] good food, we will never be able to close the tap on the illnesses that people get.”

A common thread throughout her work is an emphasis on the socio-economic determinants of health: access to housing, water, education, employment, nutritional food and so on. She said that the factors that determine whether we are sick or healthy begin way before we actually present with disease.

“If you think of something like childhood diarrhoea, this is directly linked to nutrition and to the quality of water that children drink. If you think of measles, this is linked to access to primary care facilities and vaccination. If you think of diabetes and hypertension, this is connected to access to and knowledge of good nutrition, and the ability to exercise in safe neighbourhoods.

“So, if we just fix the health system, we are intervening too late to make a tangible difference to the health of all the people in the country and beyond. And we can only do so much as doctors, but if we donʼt have housing, water, education [and] good food, we will never be able to close the tap on the illnesses that people get.”

Bridging the mistrust

In her advocacy work, this multisectoral collaboration is reflected and provides a well of inspiration for Cairncross. From campaigning for a basic income grant to working with housing activists and advocating for better conditions for women working on farms, South Africa needs to tap into the energy of existing social movements and bridge the mistrust between communities and official government structures, she said.

“I meet women and men (but mainly women) in communities who are doing incredible work locally and I just feel that they donʼt get the recognition and we donʼt learn from them. We are not doing enough to tap into this energy to help us during one of the biggest public health crises of our time,” she added.

“Being connected, even in a peripheral way, to these movements is inspiring.”

“For me, being connected, even in a peripheral way, to these movements is inspiring and I wish that our state structures would work more on harnessing and respecting that energy.”

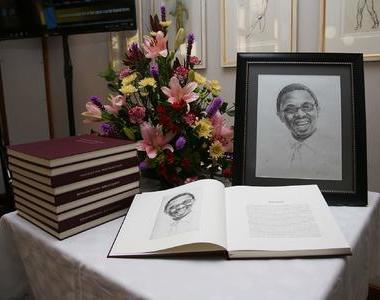

It is clear that Cairncross is far more comfortable discussing her work as an activist than drawing any attention to her personal life. Born into a deeply political family and having joined the Treatment Action Campaign’s fight for antiretroviral drugs in 2001, it is easy to understand her inherent propensity toward activism and infusing a social justice lens into any work she is involved with.

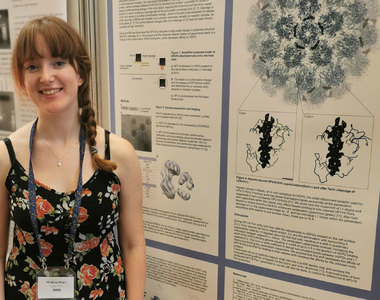

Cairncross’s substantial contribution to health activism makes it easy to forget that she also has a very busy day job as a clinician, as an academic who was promoted to associate professor in 2020, and as a mother of two children.

She admits that it’s not easy to juggle it all.

“By the end of 2020 … I had to breathe and rest to find the usual hopefulness and optimism I have in people and in the impact of our efforts,” she said.

“I suppose the lesson is that when we engage with the world, we need to do so mindfully, respecting our energy and need for rest. Because when people burn out, it is no longer possible for them to continue to participate in a meaningful way with this important work.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.