Ground-breaking project to monitor well-being of wildlife using robotics and AI

25 May 2022 | Story Niémah Davids. Photo Supplied. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 5 min.

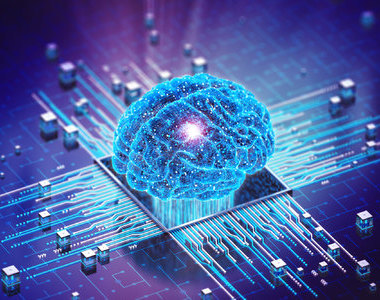

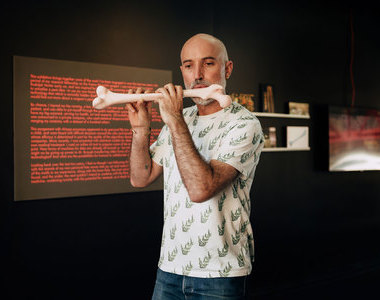

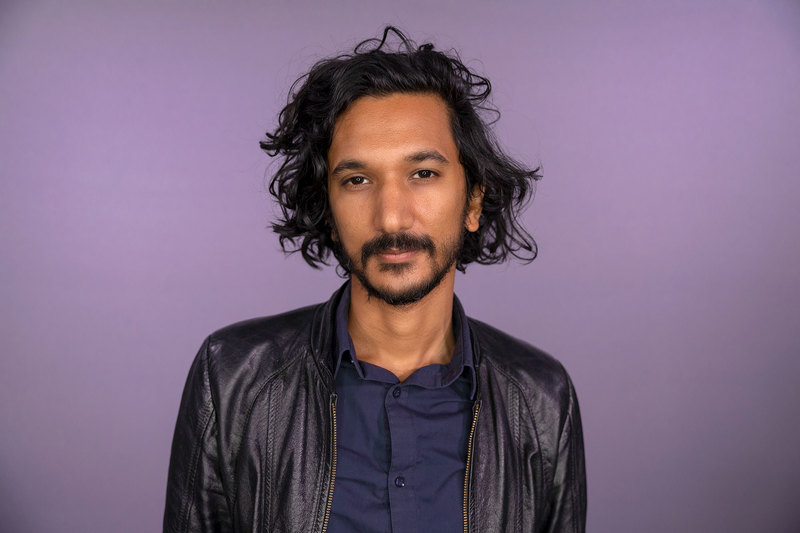

In a novel transdisciplinary project, University of Cape Town (UCT) academic Associate Professor Amir Patel has set his sights on using robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) to effectively monitor the health status of wildlife – a game-changer for the fields of ecology and conservation management in South Africa.

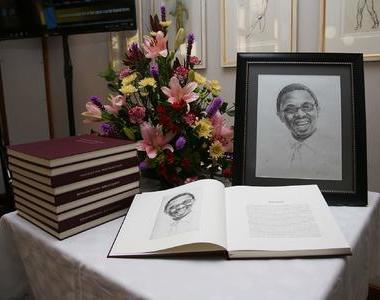

Associate Professor Patel is based in UCT’s Department of Electrical Engineering in the Faculty of Engineering & the Built Environment (EBE). He has recently been named the 2023 recipient of the prestigious Oppenheimer Memorial Trust (OMT) Fellowship Award. Patel will use the funds associated with this award, which is valued at R500 000, to fast track his latest work during his sabbatical at the University of Oxford next year.

The OMT annually awards a limited number of grants to support scholarship at public higher education institutions in South Africa. These awards are intended especially for full-time academics undertaking sabbatical study, and preference is given to candidates with proven records of teaching and research.

“I am beyond excited to spend my sabbatical at the University of Oxford to accelerate this project.”

“I’m still in a bit of shock that I’ve been awarded the Oppenheimer Memorial Trust Fellowship Award for the second time. I am beyond excited to spend my sabbatical at the University of Oxford to accelerate this project. I believe that it will be a catalyst for my career, and I look forward to seeing how it all unfolds,” he said.

Monitoring wildlife

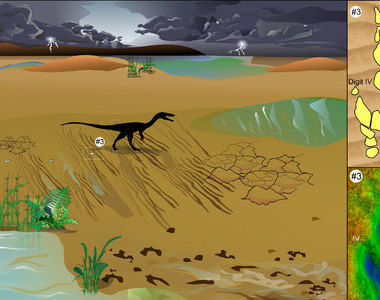

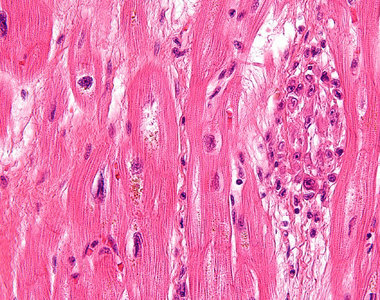

According to Patel, an increasing number of wild animals are contracting diseases from both humans and domestic animals, and it’s challenging to monitor and assess their health status.

“It’s very difficult to monitor animals in the wild because it requires drawing their blood, assessing their droppings, and other time- and resource-intensive monitoring that does not allow rapid disease identification and interventions to address the problem,” he said.

His project has been developed in direct response to this challenge. The plan, Patel explained, is to employ techniques traditionally used in robotics, such as computer vision, machine learning, mechanical modelling and sensor fusion, to remotely measure the vital signs of wildlife. He has already started the data collection process and developing the algorithms to accurately monitor lions, as the first attempt.

“Novel diseases can decimate entire wildlife populations and ripple through ecosystems as pathogens find hosts without immunity. As an example, lions – an endangered species – can contract canine distemper from domestic dogs, or bovine tuberculosis from cattle, which can then spread through a pride if not detected early,” Patel said.

His technology will provide ecologists and veterinarians with an early warning system to help them detect if an animal is ill, which in turn could help prevent the spread of a disease through the animal population and back to humans.

During his time at the University of Oxford, he will work closely with Andrew Markham, a professor in computer science and a UCT PhD alumnus. Patel plans to combine Professor Markham’s data-driven techniques with his own algorithm-driven approach to solve this “interesting problem”.

Management and monitoring strategy

Patel has spent roughly a decade developing systems to understand the biomechanics of wildlife, cheetahs most specifically. His latest project is an extension of this work and he is excited to study wild animals through a robotics lens and to provide novel insight into their well-being.

In the long-term, Patel hopes that his technology will form part of a broader management and monitoring strategy at national parks in South Africa. Despite its infancy stage, he said, officials at South African National Parks (SANParks) have agreed to use this technology in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park – a wildlife preserve and conservation area on the border of South Africa and Botswana – and in the Kruger National Park in Limpopo, once it’s ready for roll-out.

“This project gives me an opportunity to work on a platform that is more immediately applicable to the African continent.”

“My work [to date] has been quite blue-sky – studying cheetahs to build more agile-legged robots. This project gives me an opportunity to work on a platform that is more immediately applicable to the African continent,” he said.

“In control engineering we have a saying that goes: ‘You can’t control what you can’t measure’. I am convinced our technology will enable more efficient conservation management.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

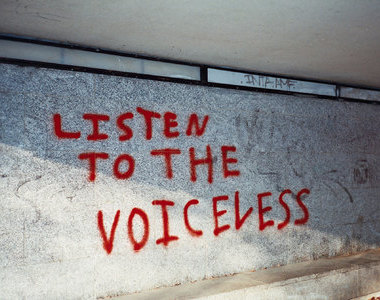

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.