District Six: belonging and place; lessons for planners

11 February 2021 | Story Helen Swingler. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 10 min.

Growing up on the Cape Flats, Alicia Fortuin didn’t know much about District Six. Her first encounter was during a class visit to the District Six Museum as a student. But there, in the records of a long-gone community, she found familiar reflections of her own family’s forced removal from Vasco, Goodwood, to Bishop Lavis and then Mitchells Plain. On the 55th anniversary of the passing of the legislation on 11 February 1966 that declared District Six a whites-only area, Fortuin reflects on the forced removals and talks about recreating a lost community.

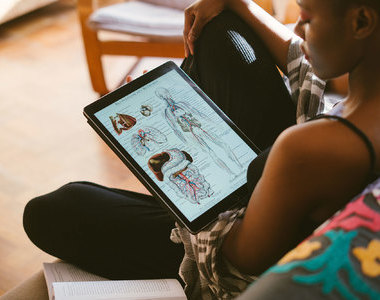

“I was so angry,” said the University of Cape Town (UCT) PhD candidate in the African Centre for Cities. It had taken that long to comprehend the reality of her coloured identity and culture, embedded in the Cape Flats where people of colour were resettled in the wake of the Group Areas Act.

“I learnt the stories of my life in academic papers: what I experienced growing up was spoken about in sociology journals.”

There it was: the working-class, female-headed household, children leaving school early to supplement their family income, travelling long distances to blue-collar jobs in a city structured to disempower its poorest. Fortuin was struck by how she had managed to disrupt that narrative; the first generation to do so.

Memory and homecoming

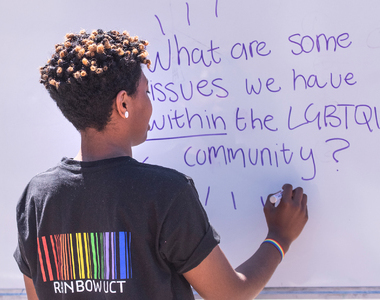

“But it’s where I speak from,” she said. Her sense of deep injustice, repeated in the city’s spatial development, steered her to a master’s in city and regional planning. Here was a tool she could use to change things. Using the “monster” case study of District Six for her thesis, Fortuin examined the convergence of issues such as belonging, memory and place, as well as civic participation, democracy and citizenship.

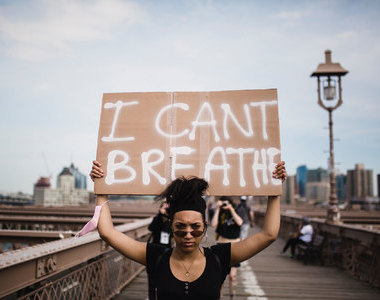

“The material history of the story of and the destruction of District Six is buried all over the city,” she said. “I was interested in understanding the spaces of participation in the restitution and redevelopment processes of District Six and the lessons for urban planners who work in these kinds of participatory spaces. And particularly in communities that have experienced trauma, dispossession and displacement.

“What does it mean to be a citizen in South Africa, in a city like Cape Town that is so unequal?”

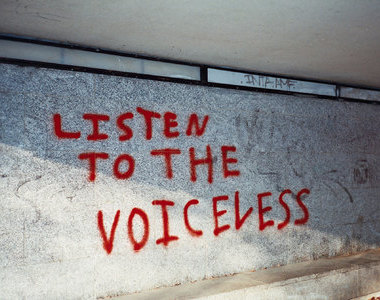

“As planners, how do we listen to these grievances and take these into account during redevelopment? Are we listening to the real issues? What does it mean to be a citizen in South Africa, in a city like Cape Town that is so unequal?”

But how to negotiate with a community where “community” had become a contested word in the case of District Six and restitution?

“In District Six there were people that owned land; others were tenants. There were multiple families living in homes and buildings. And there were many people that couldn’t trace that they had lived there. And because of the many, many years that passed, this became a point of contestation around rights to return to the land, and compensation.”

Planners had to play that intermediary advocacy role of listening to communities and taking that feedback up to city, province and national government. Land restitution is a national mandate, but urban restitution is administered by local government, and the redevelopment of land post-settlement and post-transfer becomes a municipal responsibility.

Because of the history of forced removals in District Six and the politics of community, Fortuin focused on developments from the 1980s to 2013; the critical post-1994 period when the new government and the Restitution of Land Rights Act should have smoothed the way for land claimants. But it continued to be fraught.

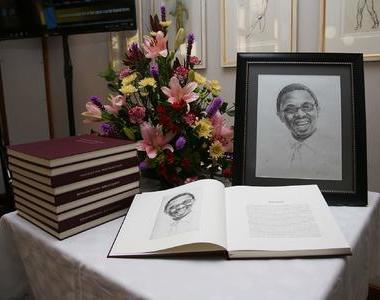

Memory and belonging

The issue of memory, community and belonging is harder to address, said Fortuin.

“These people were historically disenfranchised [and] disempowered, and by the miracle of 1994 were given an opportunity to return. It is important to create a space that imbues the recognition and expression of rights of previously disempowered citizens. They need to be given the space and opportunity to speak to the memories of that space.”

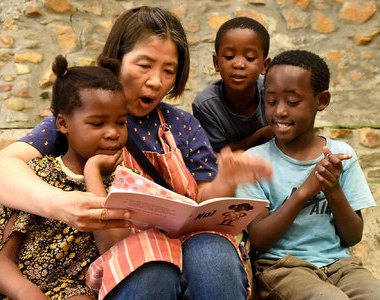

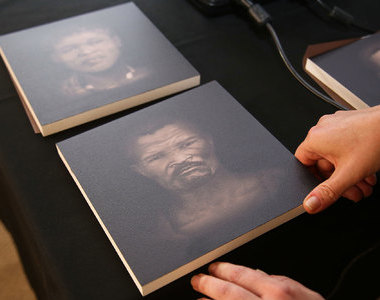

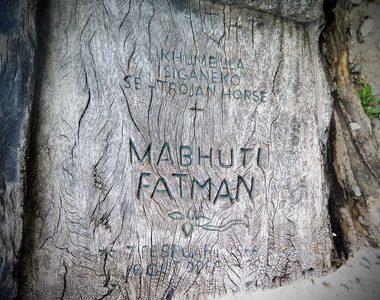

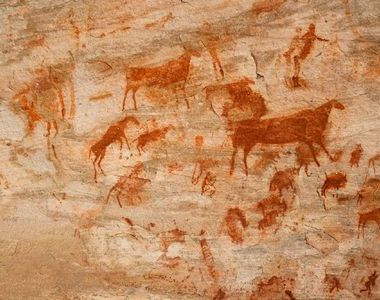

In 2015 the Peninsula Maternity Hospital Memory Project did that. The hospital opened in 1921 but closed after 71 years, demolished for the new District Six Community Day Centre. The District Six Museum got permission to host a memorialisation project there. This reflected the many layers of history associated with the site. Importantly, members of the community contributed art and storytelling.

It was a powerful moment, said Fortuin.

“They gave individuals the opportunity to speak about their memories of District Six: where they used to live, where they spent time and how they frequented the spaces. At first they were hesitant. But for many it was liberating to go back to the spaces in their memories that they’d forgotten.

Community ‘in absentia’

It not only gave individuals an opportunity to express themselves artistically, to connect to place, but to realise that their memories and experiences were important, she added.

Right on Table Mountain’s doorstep is this scar in the physical space – and in the mental space of those who lived there.

“It’s about honouring those memories,” said Fortuin, “but also being cognisant of what the space is now because the community is fractured. You’re trying to create a community in absentia, as the people were scattered all over Cape Town.

“It’s really important to have that collective memory, even though you were moved to Hanover Park or Manenberg or anywhere on the Cape Flats. You have that.”

Other South African communities, such as Sophiatown in Johannesburg and Cato Manor in Durban, have dealt with restitution and forced removals too, but District Six is particularly traumatic, Fortuin said. It was wiped out.

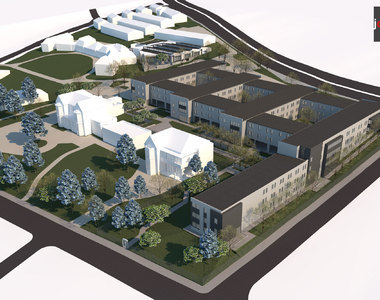

“Sixty thousand families were removed, and now there’s this vast, barren space etched into the landscape, into the CBD, into the very prominent space in the city. Right on Table Mountain’s doorstep is this scar in the physical space – and in the mental space of those who lived there. Later, people didn’t want to develop the land. They felt it was haunted.”

Land economics

Urban planners must also consider that land restitution runs parallel to a market-driven allocation of land.

“Because the District Six land is literally in the CBD, the value is high. So technically, in economic terms, the [Restitution of Land Rights Act] is the only way that the beneficiaries, poor working-class people, could have returned to this land. And unlike office or commercial space, residential land doesn’t make money in the CBD. Planners and developers must be incredibly creative to make it financially viable.”

What’s clear is that planners can’t think about District Six in an ahistorical way, said Fortuin.

“We have to think about the history and the legacies of dispossession and displacement and the real trauma and pain associated with that, of the loss of symbolic and material things. And the community’s democratic right to be able to return.”

What also stands out for her is the power of community and grassroots activism that propelled the case of District Six, despite the legal, political and other obstacles.

“It was almost entirely community led,” said Fortuin. “The participation underscored the goal of democracy. And democracy means power to the people. The case of District Six demonstrates that so well; it was the community who, in absentia, deconstructed and, all over the Cape Flats, reconstituted this idea of community.”

“They had a collective and connected goal: to come back, to return to this land.”

“Because of this united front, they were determined. They had a collective and connected goal: to come back, to return to this land. And this was a victory against the backdrop of the story of District Six. The fact that the land was given to the community, in principle at least, is a testament to the power of community and grassroots organisations and activism in a democratic South Africa.

“So, in that sense, it’s as urban planner and academic Leonie Sandercock said: It was ‘a thousand tiny empowerments’.”

Missed chance

However, the challenge for planners, the state and others involved is to acknowledge that District Six was a missed opportunity to bring working-class people back to the CBD, said Fortuin.

“When land restitution is delivered alongside market-driven values, it becomes difficult to reunite community and place.”

But these are the case studies that set the perspectives of the Global North and Global South apart, she added. Much of Fortuin’s work lies in developing the perspective of the Global South.

“You can no longer use theories from the Global North to discuss the realities of the cities, communities and settlements in the Global South. And that’s exciting because it is about understanding the everyday links to both local and national policy imperatives.

“It is those intricacies and how people navigate the cities and places they live and work that will guide our local and national policies.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.