Breathing life into history

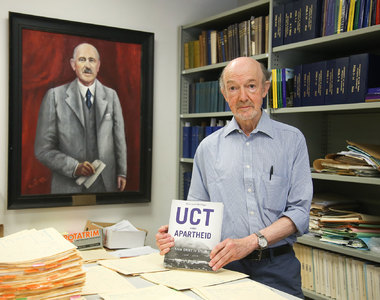

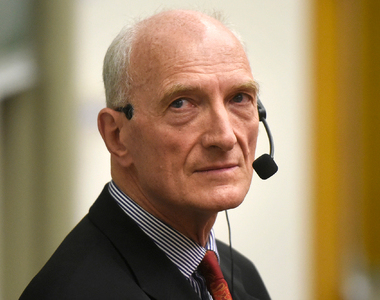

04 November 2019 | Story Nadia Krige. Photo Brenton Geach. Read time 8 min.In all his years of writing about long-past conflicts and clashes in the Roggeveld region of South Africa’s Northern Cape province, Professor Nigel Penn from the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town (UCT) never anticipated that his work would find poignant relevance in the present.

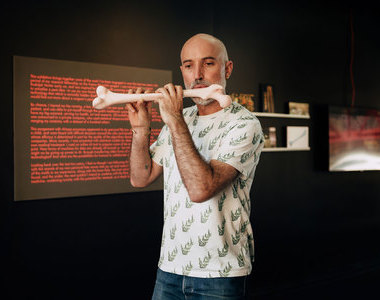

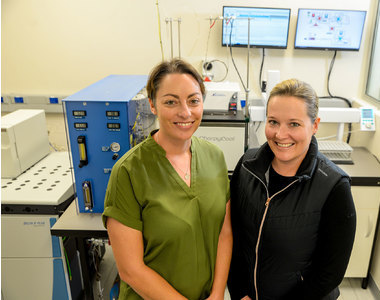

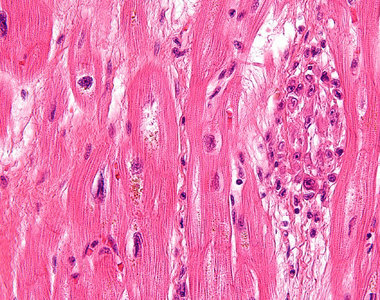

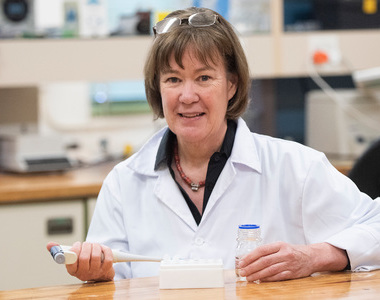

It all started in February 2017 when Dr Victoria Gibbon, from the Department of Human Biology, Division of Clinical Anatomy and Biological Anthropology, performed an archiving audit of the university’s skeletal collection and identified 11 human skeletons that had been obtained unethically.

A moratorium was immediately placed on the remains, and an investigation began on how to move forward.

It soon emerged that, of the 11 skeletons, nine had been donated to UCT by Carel Coetzee – a farmer’s son and medical student – between 1925 and 1931. Eight of these had been exhumed at Kruisrivier, the Coetzee family farm just outside Sutherland in the Roggeveld region of the Northern Cape, and are believed to be the remains of San and Khoe farm labourers.

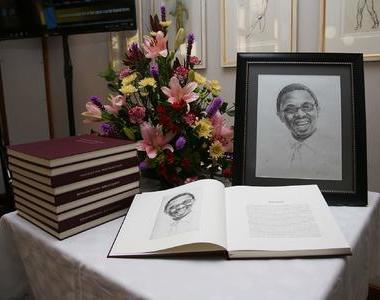

It was decided that the university had a responsibility to return the skeletons to their place of origin where they could be laid to rest near their families, and that the process would start with the nine Sutherland individuals.

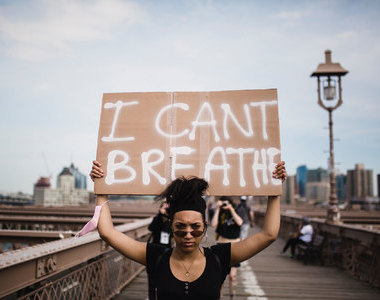

Having established himself as an expert on the history of this relatively obscure, but nonetheless blood-drenched region of South Africa, Penn was approached to contribute to this important process of restitution.

“They were not anonymous bones lying somewhere in the veld. These were individuals who had been buried, with names.”

Contextualising the past

“My role in the Sutherland project has really been to provide historical background to the region and offer a measure of context to what might have been going on in the 19th century,” he explained.

Although his area of expertise is 18th century history, he combined his deep knowledge of the region with archival research, as well as visits to Kruisrivier. This combination assisted him to gain a clearer understanding of what the realities of life might have been like for the nine people in question.

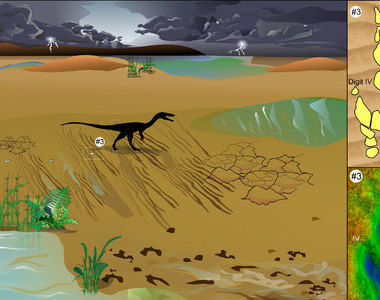

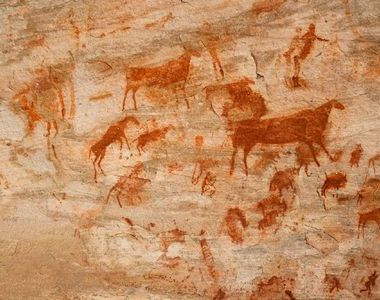

Penn described the Roggeveld as a very dry, harsh area of South Africa where conflicts and clashes between colonists and indigenous people were commonplace.

“It truly is a blood-soaked region where a great deal of fighting took place between the San and Khoe and the colonists,” he said.

“This fighting began roughly in about the 1740s and continued deep into the 19th century.”

During this era, it was also the order of the day for commandos moving through the region to shoot and capture San and Khoe people. Typically, the men would be killed, and the women and children forced to become labourers on surrounding farms.

Since it was permissible for farmers in the region to employ destitute children as apprentices or forced labour, it is safe to assume that many of the farm labourers in the Roggeveld during the 19th century were San and Khoe children who had been orphaned because their parents were killed, according to Penn.

With the abolition of slavery in 1838, an even greater burden would have been placed on these farm labourers.

Within this historical context, it is then likely that the skeletons brought to UCT belonged to San and Khoe farm labourers who had been buried with custom and ceremony.

“They were not anonymous bones lying somewhere in the veld. These were individuals who had been buried, with names,” Penn said.

“What increases the disturbing nature of [Coetzee’s ‘donation’] is the fact that these were skeletons of individuals who were probably known to him, or his father, or his grandfather.”

Walking the historical landscape

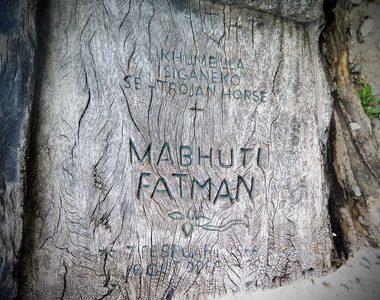

Part of Penn’s project brief was to attempt to find the graveyard from which these skeletons had been exhumed.

He joined Professor Simon Hall, a friend and colleague from the Department of Archaeology, on what turned out to be a successful excursion to the farm.

“After some walking around, we discovered the cemetery. It wasn’t easy to find,” Penn said.

“Time has blended it into the veld – it’s very hard to distinguish the gravestones. It looks very much like part of the landscape.”

Walking the area was also a particularly memorable and significant aspect of the project for Penn.

The day he and Hall came upon the cemetery, he recalled, the wind was moaning through the bleak and hostile environment, creating a suitably eerie atmosphere.

“Walking around this deserted farmyard, finding bits of old pottery – both Khoekhoe and Dutch – and realising that this was a very, very early site of interaction between the Khoekhoe and the colonists was certainly an unforgettable experience.”

“It truly is a blood-soaked region where a great deal of fighting took place between the Sand and Khoe and the colonists.”

A department at the forefront of transformation

Penn’s role in a restitution project of such magnitude and historical relevance has also been a feather in the cap of UCT’s Department of Historical Studies as a whole.

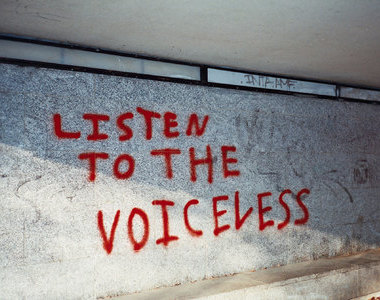

By focusing on the history that was perhaps less celebrated previously, and highlighting the stories of those who moved on the margins of society, the department has played a particularly important role in curricular transformation.

“I think the department has led the way in a type of a social history which emphasises or highlights the voice from underground, as it were,” he said.

He hopes that his role in the Sutherland project might also inspire some students to throw themselves into looking at a more rural, regional type of history.

“There are many, many other regions of the Cape or South Africa that would benefit from a similar close scrutiny.”

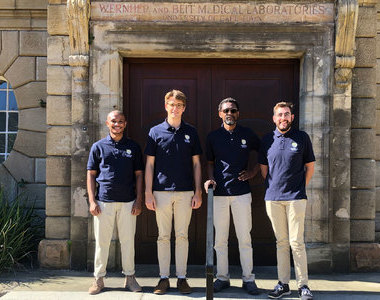

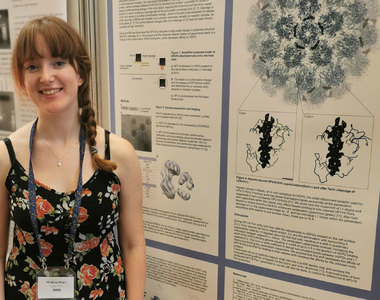

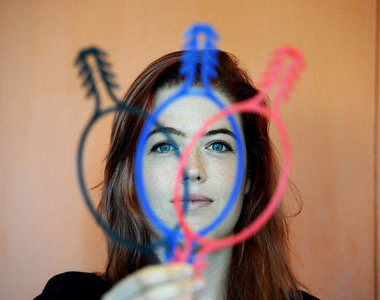

Being able to conduct this kind of research in collaboration with academics from such a wide range of disciplines – including health sciences, archaeology and even facial reconstruction – has been a gratifying experience that Penn hopes to see happening more often within the university.

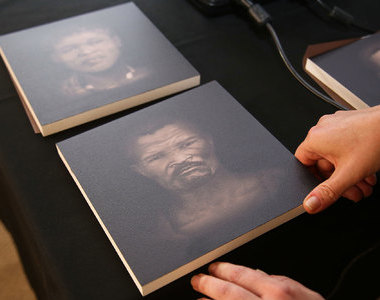

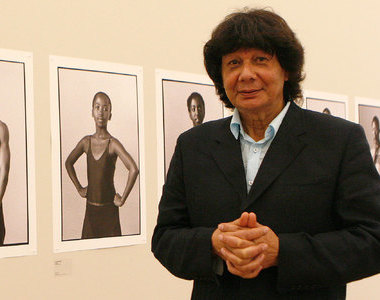

“Through the combination of these different sciences, we’ve been able to breathe life back into nine very obscure individuals who would have been lost to history otherwise,” he said.

“Now, they don’t only have a history and background and individuality – they actually have faces as well.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.