‘Lack of transformation – the result of people’s decisions, or indecisions’

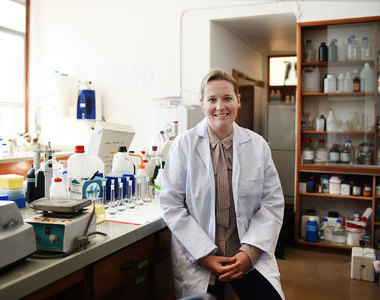

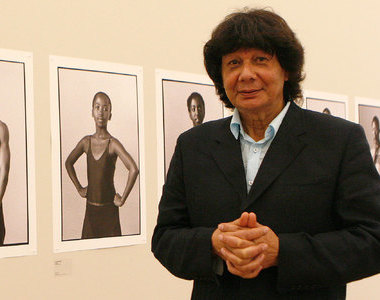

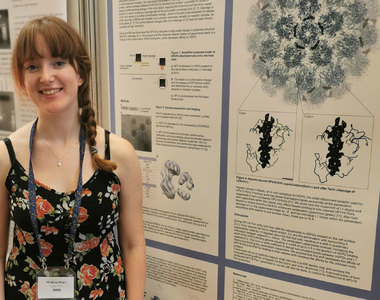

07 November 2023 | Story Maya Skillen. Photos Nasief Manie. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 9 min.

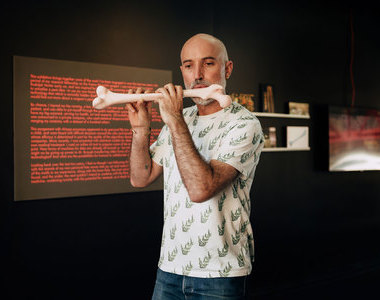

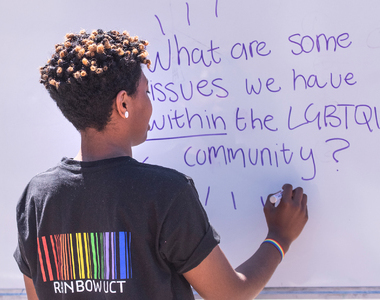

The lack of transformation in South Africa’s publishing sector took centre stage at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) third session of the “Transformation: A Humanising Praxis Think Tank Series”, with the main speakers charging that there has been little change post-democracy.

“In righting the wrongs of the past, we must look at how we arrived here. How is it that in a country where white people are in the demographic minority, their writing and literary production is at the centre of the publishing business?” questioned Anelile Dlamini-Gibixego, an assistant researcher at the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection.

Dlamini-Gibixego shared the main speaker status at the event on 1 November with Dr Athambile Masola, a lecturer in UCT’s Department of Historical Studies. Their presentations were followed by a lively discussion among participants, guided by Quinton Apollis of UCT’s Office for Inclusivity & Change.

“How is it that in a country where white people are in the demographic minority, their writing and literary production is at the centre of the publishing business?”

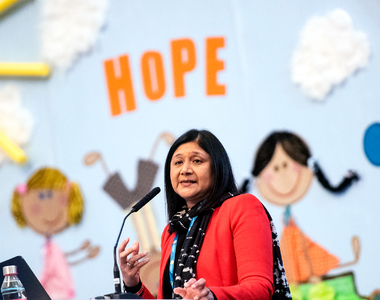

Professor Elelwani Ramugondo, UCT’s deputy vice-chancellor for Transformation, Student Affairs and Social Responsiveness, began the session with the following caution: “It is through what we do every day that we either perpetuate or disrupt hegemony – that is, the dominant interests at a systemic level.”

Ownership and editorial responsibility

In the publishing sector, argued Dlamini-Gibixego, transformation was being impeded by a scenario in which a small group of very large publishers represent more than 70% of production and revenue. Employment demographics also have a role to play; while black females dominate the sector in terms of numbers, they largely occupy positions in marketing, human resources, finance and administration, with little or no editorial responsibility.

“This generates the narratives that are pushed, and the type of books that are published and get shelf space. Those who work in the sector need to represent what South Africa looks like in order for South African stories to be shared fairly,” she asserted.

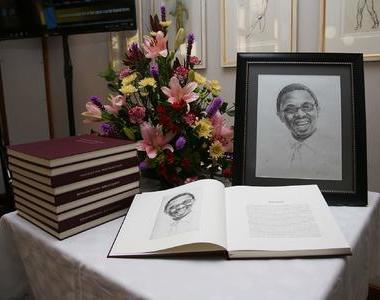

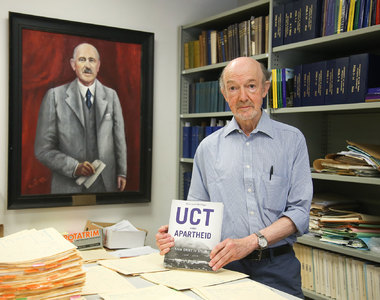

Dlamini-Gibixego’s presentation was based on the findings of a study undertaken with Dr Masola, which was published as a chapter in research anthology Mintirho ya Vulavula: Arts, National Identities and Democracy.

She also addressed what she termed the “African language conundrum”. English is the biggest revenue driver (83%), with African languages severely under-represented.

“Publishers say they will not publish original writing in African languages because people won’t read it, yet people want to read it, but can’t, because it’s not being published,” she said, adding that there was “a hunger among black South Africans to access and read stories that reflect their lived experiences”.

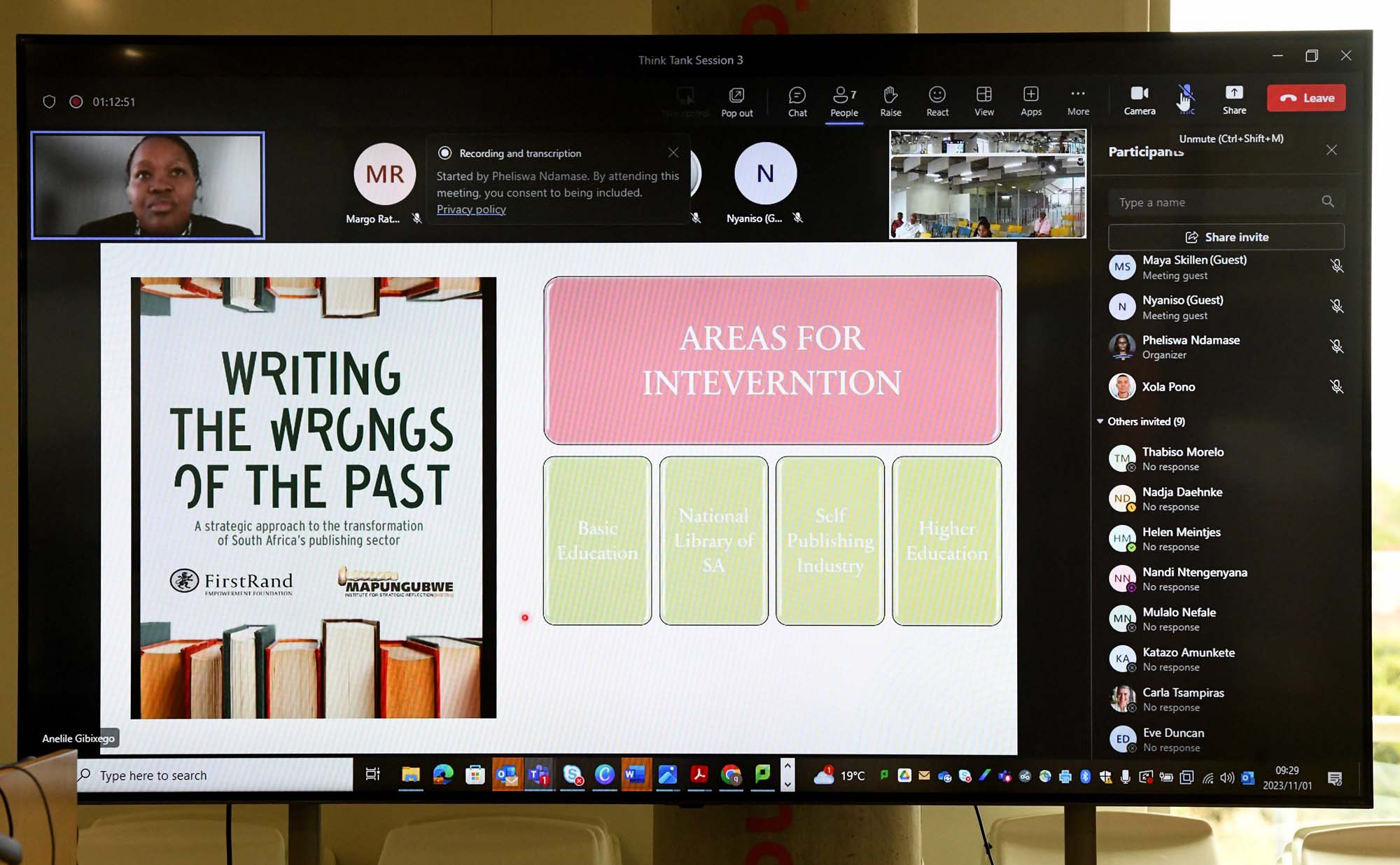

Critical areas of intervention

Other challenges to transformation included institutions affiliated with the national Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC) are being siloed; that there is virtually no regulation to guide publishers; South Africa’s literacy levels being dire; and that there is a lack of support for small, medium and micro enterprises. Local book production is also minimal, with the biggest publishing houses importing 80% of their books.

Dlamini-Gibixego’s suggestions for changing the status quo began with the basic education sector, which provides 60% of publishers’ revenue. They needed to rethink their onerous procurement processes, and curricula, to include different types of literature for learners.

National libraries fall under the archiving section of the DSAC and tend not to be promoted as active institutions that serve communities, “which they are”, she pointed out. “Libraries serve all age groups and should be preserved, funded and promoted.”

“Libraries serve all age groups and should be preserved, funded and promoted.”

Finally, the self-publishing industry needed to be empowered as an “agent for the transformation of content”, introducing new stories into the mainstream, and greater diversity into the industry.

A personal point of view

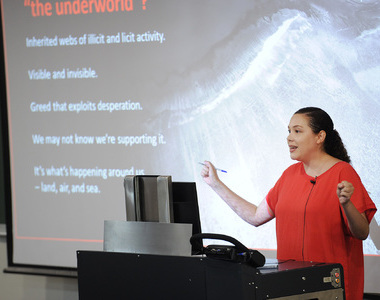

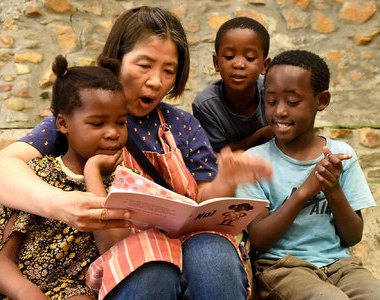

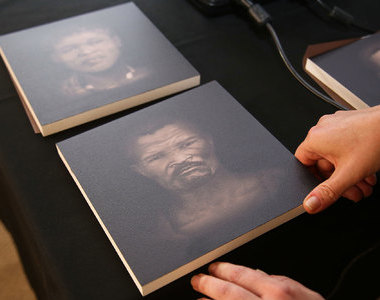

Masola offered an insightful first-hand account of her publication experience. She co-authored a young adult non-fiction series called Imbokodo: Women Who Shape Us (2022), and wrote Ifila (2021), a collection of poems published in isiXhosa, among others.

Discussing the distribution challenges she faced, she said she discovered that it was affiliations with bookshops or publishers that got her work into circulation, rather than systemic business practices like book festivals, and the use of agents or international networks.

“My publisher contacted someone that he knew at an Exclusive Books branch, which resulted in the first time that isiXhosa books were launched at Exclusive Books – ever,” she recalled.

The “tension of translation” is another hurdle that African-language writers often face, Masola said, recounting an instance when an Australian journal doing a special issue on South African literature asked her to translate her poems.

“Of course, translating into English gives you more circulation, but what does it do to the essence of the language?”

“Of course, translating into English gives you more circulation, but what does it do to the essence of the language?” she asked. “I translated three poems but insisted that they publish both the isiXhosa and English versions so people could see the isiXhosa, even if they couldn’t understand it. Just the visuality conveys that there are other languages that live in the world.”

Need for original African-language books

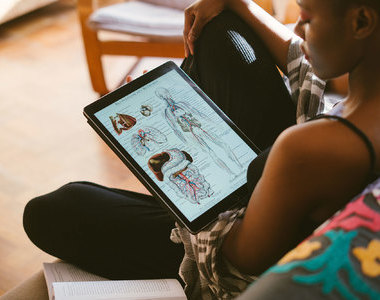

The issue of producing books in an original African language, rather than translating them from English is a pervasive one, Masola added. Additionally, children don’t get to see African languages in anything other than novels.

“If the starting point is English, does that mean that African-language stories can never be universal?” she asked.

Masola closed her presentation with the reminder that “every book has a story behind it … people who said ‘yes’ or ‘no’; people who wanted it to look a certain way; people putting it on a particular shelf”.

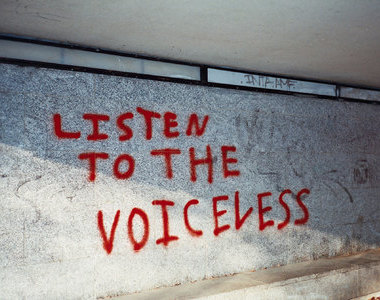

“The lack of transformation doesn’t happen haphazardly. It’s the result of people’s decisions or indecisions,” she said.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.