‘The secret communications network that helped end apartheid’

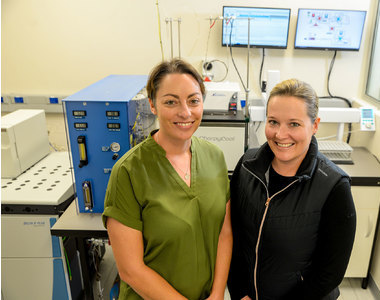

22 January 2024 | Story Niémah Davids. Photo Nasief Manie. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 7 min.

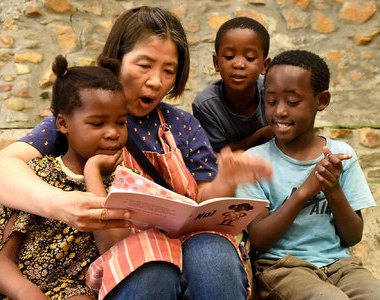

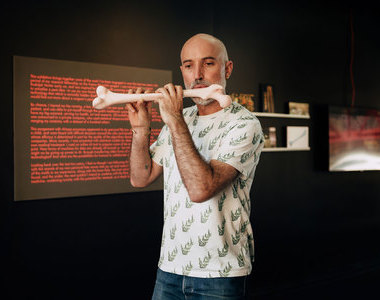

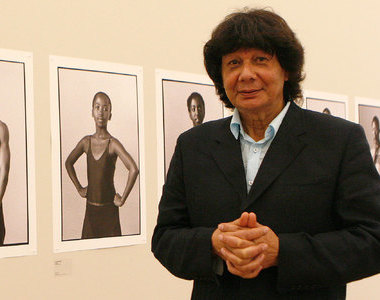

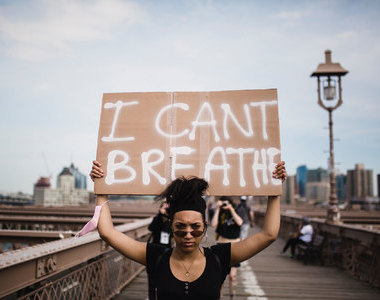

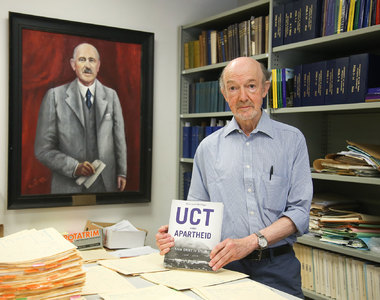

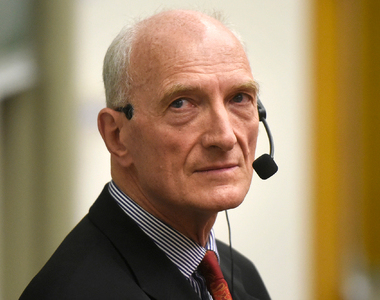

As South Africa celebrates three decades of freedom this year, anti-apartheid activist Tim Jenkin took a trip down memory lane and delivered a lunchtime lecture fitting for the time. He spent 60 minutes recounting his role in Operation Vula, a secret mission, which was spearheaded by the African National Congress (ANC) in exile and which helped led to the fall of apartheid.

Jenkin’s lecture formed part of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) annual Summer School programme – a festival of learning and the largest public learning showcase on the continent. His talk was titled: “Operation Vula: The secret communications network that helped end apartheid” and took place in the Kramer Law Building on middle campus on Thursday, 18 January.

Jenkin’s involvement in Operation Vula started after he and two others (Alex Moumbaris and Stephen Lee) escaped from Pretoria Central Prison in 1979. The trio were serving a sentence after being charged with treason. Following their escape, he fled South Africa for London where he spent several years in exile, until the unbanning of the ANC.

“Today’s talk is what happened after I got out of South Africa. So, from 1980 onwards up until 1992 when this operation ended,” he said.

Setting up underground structures

Operation Vula was initiated by the ANC in exile during the dying days of apartheid. Their mission was to smuggle leadership figures back into the country and to set up underground structures to organise “the final blows against apartheid”.

“It [Operation Vula] exceeded beyond the wildest dreams of the ANC leadership.”

“It [Operation Vula] exceeded beyond the wildest dreams of the ANC leadership – achieving more in two years than [what] had been achieved in the previous 20 years. All because of good, secure communications,” he said.

Jenkin spent a few moments taking the audience through the different modes of communication the ANC used during the 1970s. These, he said, included conventional methods like public telephones with agreed code words; coding methods in books; and concealed communication methods like invisible ink and microfilm. These techniques were regularly used but they weren’t always secure, and messages took a very long time to reach recipients.

A top-level response

Because previous attempts to get leadership figures back into South Africa from exile had failed, the plan to implement Operation Vula needed to be watertight. So, the project was kept under wraps and only a selected few were involved in the planning.

“[They] realised early on that for [Operation] Vula to be successful, the number one requirement was to [establish] good, secure communication,” Jenkin said.

He was called to Lusaka and asked to establish Vula’s communication plan. The requirements were clear: the techniques needed to be safe to use and needed to be operational from public phones and/or radios; activists in South Africa needed to communicate with those based at the ANC headquarters (HQ) in Lusaka and should receive a response in good time. Another key requirement was to ensure that the communications system allowed activists to send detailed reports and store messages and documents securely.

Discreet mission

Because the apartheid government kept a close eye on certain individuals and considered the exchange of information between South Africa and Lusaka as suspicious, the team needed a different plan. Therefore, Jenkin said, they decided that Operation Vula would carry encrypted messages from a satellite office in Durban, created especially for this purpose. The Durban office communicated messages to the ANC’s office in London, and those messages were shared with Lusaka.

“We realised [using] the system between South Africa and Lusaka would’ve made sense because it’s very close [to each other]. But when you’re using electronics, the distance doesn’t really matter. The lines were terrible in those days and, of course, anything going to Zambia was suspect from the start. So, we decided to use London as the hub,” he said.

“The first [group of activists] were smuggled into the country and they set up shop in Durban.”

“The first [group of] activists were smuggled into the country, and they set up shop in Durban and they communicated with the headquarters via London.”

Sophisticated communication system

To communicate, Jenkin said activists used a Toshiba 2 000 laptop, but the device was not nearly as nifty as the ones developed today. The laptop didn’t have a hard drive, a touch pad or a mouse. Instead, all it had was a black-and-white screen and an operating system built into the computer, which meant it started up very quickly. But running programmes were not simple and required popping a little floppy disc into the side of the machine to succeed.

How did the communications plan really work? Using a special programme, which Jenkin helped to develop, activists typed plain text onto the computer, popped in the floppy disc, encrypted the message, and sent the message to a tape recorder using an acoustic modem. An activist would then take the tape recorder to a public telephone, dial the recipient’s number, place the speaker onto the mouthpiece and push play – carrying the message from that telephone network straight to a designated, incoming answering machine in London.

The final step in the process, he said, was a short pager message to inform the recipient whether the process was successful or unsuccessful. In turn, the recipient would respond to indicate whether they understood the instruction. Over time, Jenkin said, as new technological devices and gadgets were invented and became available, the process of carrying these messages were simplified.

Successful operation

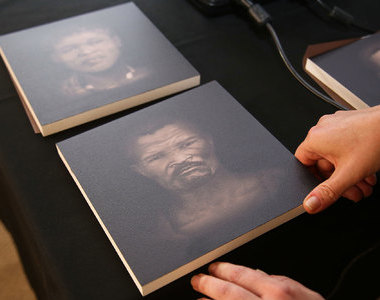

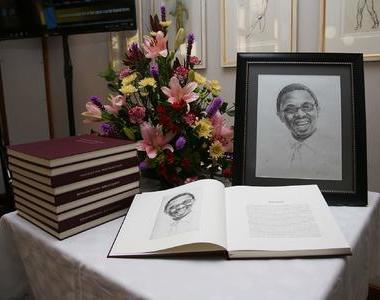

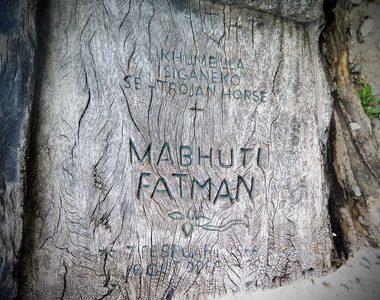

The Operation Vula communications network was a great success. It provided almost real-time connection between activists underground and those based at the HQ and ensured that top ANC leaders could return to South Africa. Thanks to the operation, no one was arrested, and it enabled the free flow of money, resources and other information between activists in exile and those in the country. What’s more, it connected Nelson Mandela – who was still incarcerated – to the ANC, during a time when the terms of his release were being negotiated.

“Operation Vula connected Mandela [to the outside world]. Mandela was actually communicating with the ANC headquarters and the regime didn’t know that. They thought they had him isolated in this prison and they thought he had no way of communicating. But meanwhile, he was actually sending long messages through the system. That was the crowning achievement of Operation Vula,” Jenkin said.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

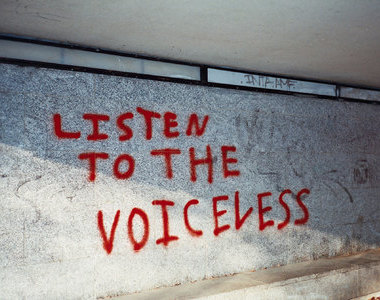

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.