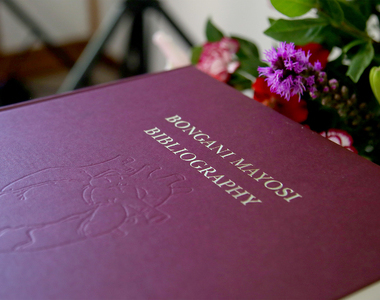

Flute from his femur – A researcher’s journey with healthcare tech, AI

27 February 2023 | Story Helen Swingler, Ralph Borland. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time >10 min.

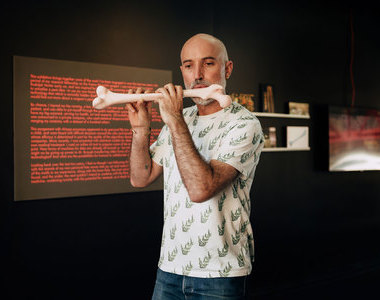

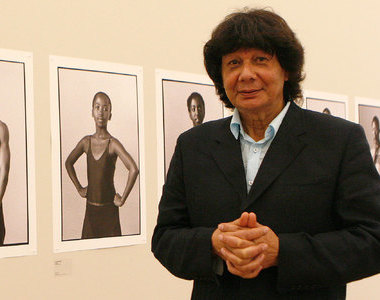

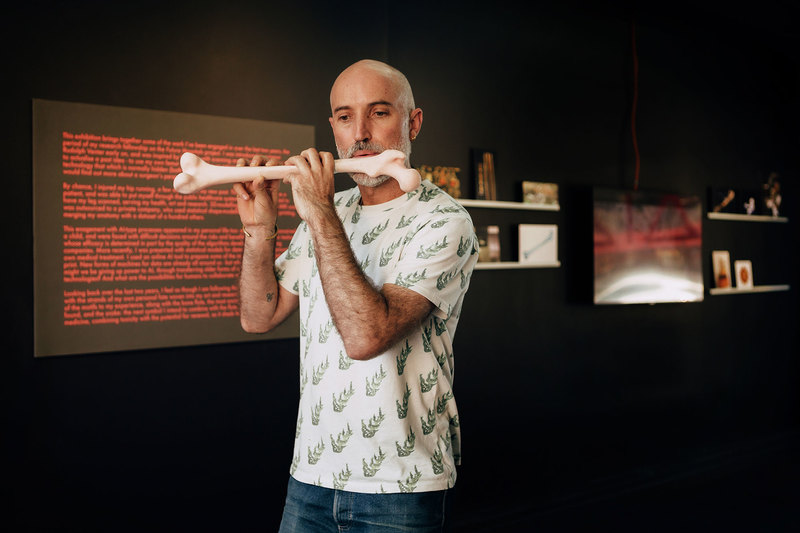

Sweet and clear, the ethereal sound of a flute greets visitors to artist-researcher Dr Ralph Borland’s exhibition in Woodstock. But the instrument yields a surprise: it’s been crafted from a human femur bone, a to-scale 3D replica of Dr Borland’s own thighbone.

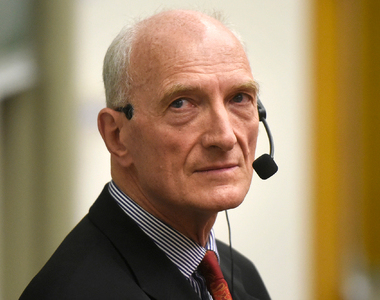

The exhibition, AIAIA – Aesthetic Interventions in Artificial Intelligence in Africa, caps Dr Borland’s two-year collaboration with a surgeon at Tygerberg Hospital, and a parallel personal journey that intricately weaves together his art, his research, and his lived reality.

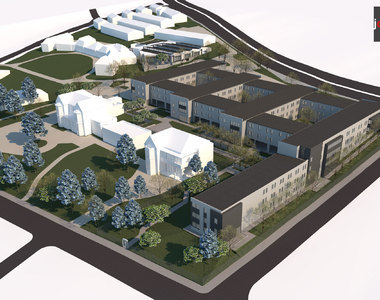

His project investigates emerging technologies in healthcare through collaboration. A Carnegie Corporation of New York-funded junior research fellow, his work is one of seven strategic projects under the umbrella of HUMA’s Future Hospitals: 4IR and Ethics of Care in Africa initiative. This reflects critically on the role of artificial intelligence (AI) and other technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in the future of hospitals in Africa.

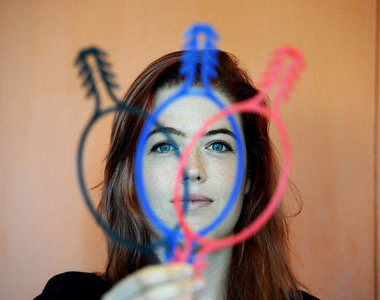

Borland’s research focuses primarily on the potential for positive human–machine collaboration, amid the negative impacts of new technologies on human experience, such as the threat of automation to human skills, for example.

He asks, “What choices can we make to use technology appropriately to enhance human skills and experience?”

Bone instruments in history

Orthopaedic surgery is one of the specialisations benefiting from innovations in biomedical engineering, such as 3D printing. At Tygerberg Hospital, orthopaedic surgeon Rudolph Venter works in his 3D orthopaedic laboratory to develop low-cost methods for 3D-printing patients’ bones so that surgeons can practise the sometimes complex procedures beforehand. Dr Venter’s work presented a unique opportunity for Borland to explore an existing idea for an artwork using a replica of his own femur.

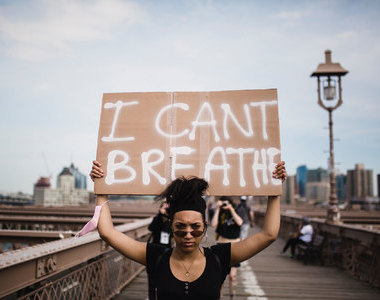

Borland had previously repurposed his own body parts and functions for artwork. For example, his art-design piece Suited for Subversion (2002), in the permanent collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art, is a suit made for protestors that amplifies the wearer’s heartbeat and makes it audible outside the body.

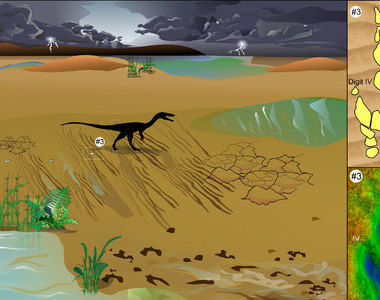

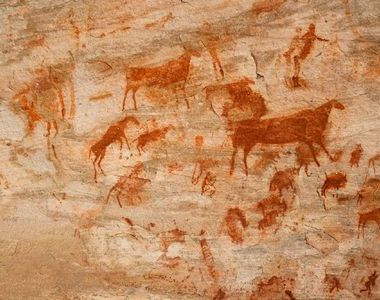

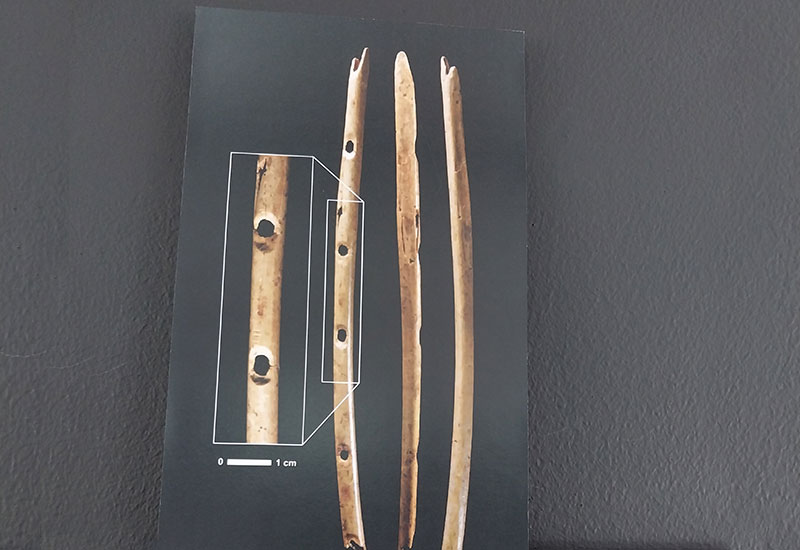

His current project emerged from a concept, first framed 10 years before, for using his bones as material for an artwork. This developed into a proposal for a bone flute made from a replica of his femur, tapping into a long history of musical instruments made of animal and human bone.

“The artwork plays on the history of the bone flute as an iconic musical object, as well as on emerging technologies in healthcare,” he explained.

Borland also links the work to the symbolism of the Danse Macabre, a popular motif in Western European art, poetry, literature and drama, in which the dead, represented by skeletons, dance with the living. It was a reminder of the universality of death, particularly after the Black Death and other epidemics swept Europe in the mid-14th century.

Musical instruments made of bone have also been found at Neanderthal sites, the earliest dating back 53 000 years.

In the 21st century, AI and digital technologies for making bones and body parts have introduced new conundrums for ethicists and medical sciencists, as Borland discovered when he proposed using a replica of his own femur.

“The exhibition explores some of the concerns around these technologies: the impact of automation on human experience, access to technology for patients, AI as a form of divinity and the possibilities of human–machine collaboration,” he noted.

Unique collaboration

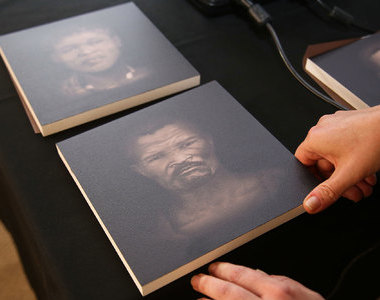

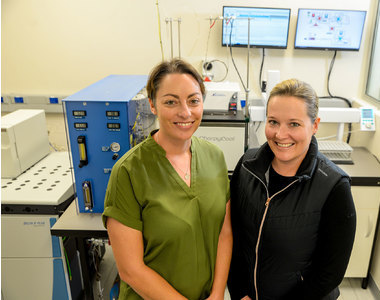

Once Borland’s femur had been 3D-printed by CranioTech, he, Gigli and Venter came together in Venter’s orthopaedic laboratory to carve holes into the creation, employing the same tools and processes Venter uses for his surgical simulations on 3D prints.

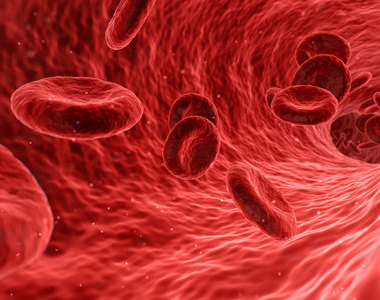

To recreate Borland’s thighbone, Venter and medical technologist Bernard Swart used MRI images obtained following a running hip injury that the scholar sustained in 2021. Once the bone had been digitally printed, Gigli advised on the precise places the embouchure (place for the mouth) and other holes should be drilled and tested the instrument for pitch and sound.

Up close and personal

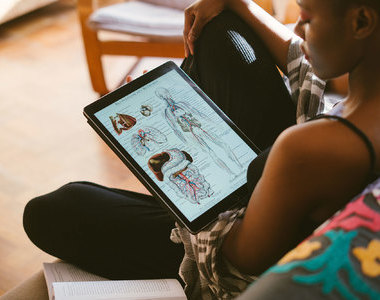

Borland wasn’t to know how intimately he would get to know Cape Town’s hospitals – not as a researcher, but as a patient, when his leg and hip were scanned in 2021. Using these opportunities, he collected data for his personal health and for his art and research.

In the hospitals he was confronted by the real environments his art-research project engages with. A series of images he took in Tygerberg Hospital show the long, cavernous corridors, empty spaces, regimented rows of empty chairs and the artificial lighting of the ageing public hospital and the new, high-tech orthopaedic laboratory within those spaces.

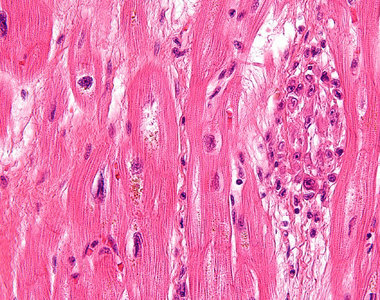

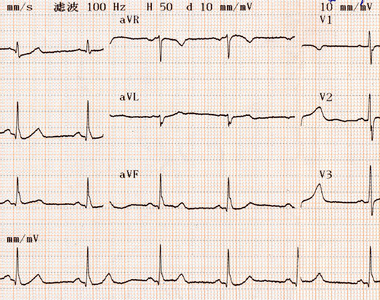

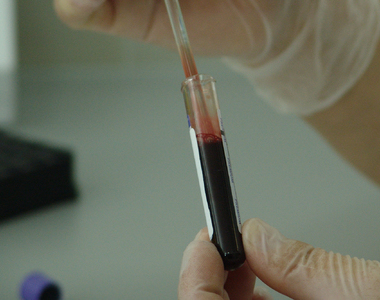

Further into his fellowship, his health took a more serious turn. Based on a family history of cancer, he booked a colonoscopy, and his surgeon found a tumour. Biopsies, CT scans and an operation followed.

To determine his genetic risk for a recurrence of cancer, his age and cancer staging were fed into an online algorithmic tool, and he was presented with the option of chemotherapy to reduce the chances of that happening.

These personal experiences became woven into the exhibition material. One of the exhibits is a timeline of the two-year research project, divided into “Research and Art” and “Personal”.

“Part of my intention with this exhibition is to acknowledge and work with the subjective aspect of research, framing the researcher not as an absent, objective voice, but as an active participant in their work,” he said.

Who is coding, and for whom?

As an artist and researcher who has worked with technology for the past 20 to 30 years, Borland said he is excited by and critical of the role of emerging technologies. “I’m excited about its creative potential, and critical of its commercially led intrusion into our work practices and everyday lives.”

What Bone Flute does is to concretise the idea of human–machine collaboration, the leitmotif of his exhibition.

“It links ancient human creative practices with new technologies. As my friend and artist Gerhard Marx observed, it is a bone animated by breath, an object with life in it, activated by the human. This should be the guiding principle for the development of technology, the centring of the human. This is the core idea of what is now being called the 5th Industrial Revolution.”

He added: “Looking back over the past two years, I feel as though I’m following threads through the labyrinth, with the strands of my personal fate woven into my art and research. The labyrinth became one of the motifs to my experience – along with the bone flute, the most ancient musical instrument the world has found.”

Next, he plans to turn Bone Flute into an automation, creating a self-playing, automatic instrument, using the shape of a snake (a boomslang, specifically) wound around the length of the flute.

It seemed a natural choice, given the themes, emblems and symbols he has already explored.

“The snake is a symbol for medicine, combining toxicity with the potential for renewal, as it sheds its skin and emerges anew.”

This programme is funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Wenner-Gren Foundation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.