Trains least safe public transport for women

26 February 2020 | Story Helen Swingler. Read time 9 min.

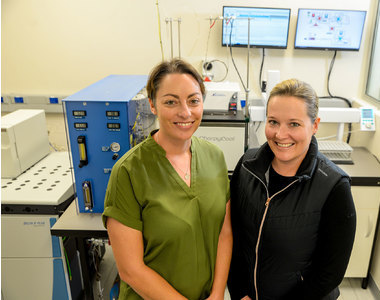

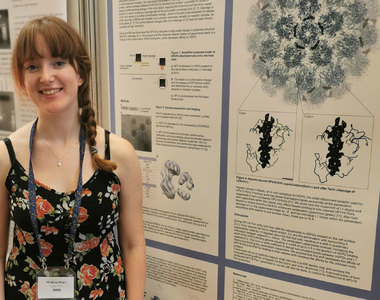

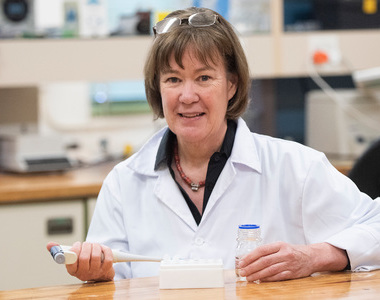

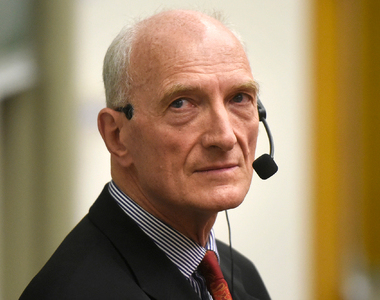

Although rail offers the cheapest daily commute, trains are the most dangerous mode of public transport for South African women, says an award-winning paper by the University of Cape Town (UCT) transport engineer Professor Marianne Vanderschuren.

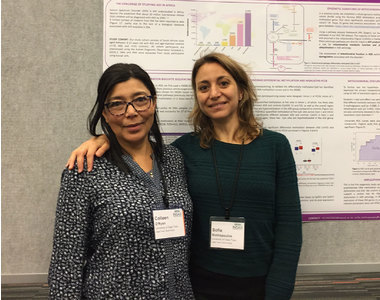

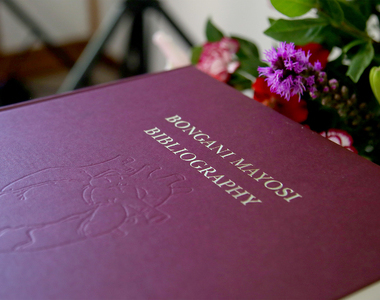

The co-authored paper, “Perception of Gender, Mobility and Personal Safety: South Africa Moving Forward”, published in the Transportation Research Record Journal, won the Charley V Wootan Award, presented in January.

This annual award is made by the United States Transport Research Board (TRB) for the best paper in transportation policy and organisation. Vanderschuren collected the award at the Transport Research Board’s 99th Annual Meeting in Washington, DC.

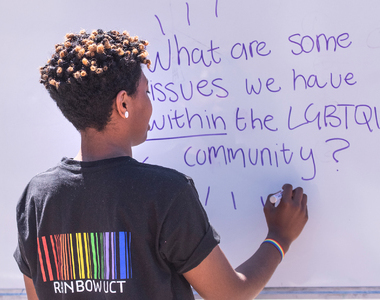

“It has been established that transport planning is male dominated. More guidance is needed for transport planners and city authorities to plan better and more gender-sensitive networks and services,” said Vanderschuren, who is based at the Centre for Transport Studies in the Faculty of Engineering & the Built Environment.

Women’s priorities must be met if urban transport is to cater for the needs of the entire population. Currently, transport is not gender neutral and is in sharp contrast to the country’s progressive Constitution, she added.

“Treating communities as homogenous is a major flaw in current policies and practices.”

The commuter safety issue must also be viewed against the South African National Development Plan’s 2030 vision, which includes improved access to economic opportunities, social spaces and services by bridging geographic distance affordably, reliably – and safely.

As such, Vanderschuren’s findings have significant implications for the country and call for more nuanced public transport policies.

“Treating communities as homogenous is a major flaw in current policies and practices, which don’t recognise that women and men have different needs and patterns of mobility and accessibility.”

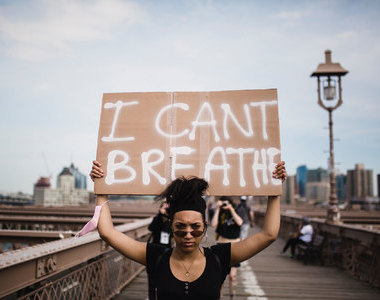

Harassment on the move

Her research has shown that harassment on the bus and train as well as at public transport hubs and stops strongly influences how women choose to travel in their daily commutes. The safety issue is aggravated by the urban environment, poor lighting at stations, in subways and along the pathways en route to transport hubs.

Vanderschuren’s study examines how security data on South African women compares with international studies.

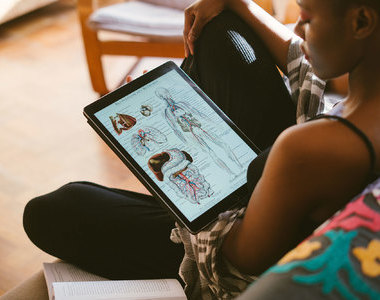

The first section of the two-part study sets the context by examining international trends in travel-pattern differences between women and men. The second part examines data on mobility, based on the South African National Household Travel Survey (SANHTS) 2013, looking for trends in trip frequency, duration, distance and mode choice.

Women’s travel trends

Literature from different parts of the world shows that women make more personal trips than men of the same age group. Typically, women make multiple stops, or “trip chains”, combining shopping, collecting and dropping off children, visiting family and running errands, paying multiple fares and travelling during off-peak hours when public transport services are less reliable and waiting areas less busy.

In South Africa more women than men (26.5% vs 23.5%) use public transport, and more women (31% vs 27%) travel to work. In line with international literature, South African women make 2% more “care trips” (taking children to school, clinic visits, etc), and 8% more shopping trips.

The second part of the study also unpacks harassment experiences in Cape Town. This is based on fieldwork with four focus groups (including women from Langa, Atlantis and other areas), as well as interviews with 285 rail passengers.

Overall, between 20% and 56.5% of household heads consider parts of the public transport journey risky. Trains are considered the least safe and are used because fares are cheaper.

Vanderschuren said that an alarming percentage of household heads expressed concerns about Metrorail train services, run by the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa, which is responsible for 2.2 million trips daily in the country’s major urban areas.

Household heads were particularly concerned about the walk to and from the station (56.6%), and many worried about the time spent on the train (47.3%) and at Metrorail stations (32.4%).

“When respondents travel alone, especially female passengers, they often meet up with the same people while out travelling to keep an eye out for each other,” said Vanderschuren. “If they are not planning to travel the next day, they let their fellow travellers know.”

The focus group reduced risks in the same way. However, the time of day didn’t appear to affect the risk of harassment significantly in the South African context. This contradicts global findings, where travelling at night is considered more dangerous.

The train passenger focus group were overwhelmingly in favour of security on and around train stations. They also called for workshops focused on youth, seen as the main perpetrators of harassment on trains.

Mobility deprivation

It’s time for a different approach, said Vanderschuren.

“Research in transport planning and practice has consistently failed to apply a social science perspective when determining patterns of transport and travel.

“There’s also too little research on this topic in the global south. There’s a systematic lack of understanding of the gender-based differences in system requirements resulting in ‘mobility deprivation’.”

Research will continue to play its part in finding solutions, she said.

“In the future it may be useful to define different categories of journey length: 5 km, between 5 km and 10 km and journeys of more than 10 km – or even journeys from one urban centre to another or across provincial boundaries.

“There is also potential to look at comparing transport users in urban centres beyond the Cape Town metropolitan area over similar distances and contrast this with transport usersʼ behaviour in rural areas.”

Policy recommendations

While the South African government has policies and strategies to invest in public transport modes to make them accessible, safe, affordable and reliable, recent investments have not resulted in the anticipated personal safety improvements.

To address the issue, Vanderschuren’s paper lists seven policy recommendations:

- Public transport integration is needed to improve public safety, especially for women, and to accommodate the care trips they make to serve others.

- Public transport and non-motorised transport masterplans should feature women’s need for safety as a unifying element for investment. Key linkages are needed between communities and public transport precincts, and should include proper lighting, paved walkways and designs that encourage safety and security, especially around train stations.

- Involvement from civil society is needed, awareness campaigns should be created, and options should be available within the law to address security concerns.

- Government should partner with minibus taxi (MBT) organisations to advocate for better security. Focus on MBT as an integral part of the South African transport system and establish it as a safe and secure service.

- Visible policing and security (24 hours) should be the norm for public transport precincts.

- The research has shown that men and women perceive safety differently in South Africa. The SANHTS addressing questions to household heads only might be limiting. Vanderschuren recommends using women within households as the benchmark for security concerns.

- The legislative framework should ensure women’s safety, but the laws aren’t implemented adequately (for example, in by-laws) and fear of harassment remains a barrier to women’s mobility and access to public transport. Although the Constitution doesn’t make explicit reference to the right to transport, access to safe public transport is intrinsically linked to the right to freedom of movement.

Vanderschuren’s co-authors were Sekadi Phayane and Alison Gwynne-Evans.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

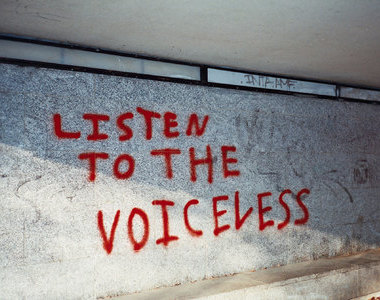

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.