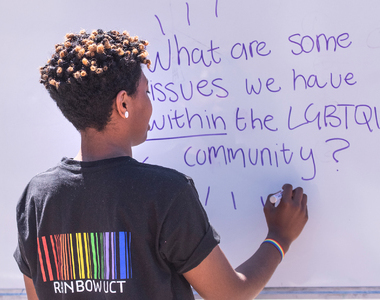

Pension law deprives most South Africans right to decide on inheritance

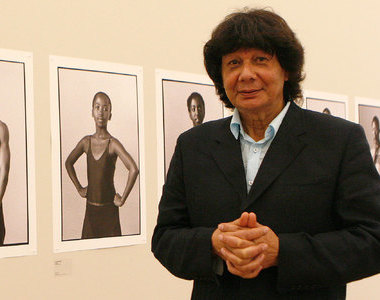

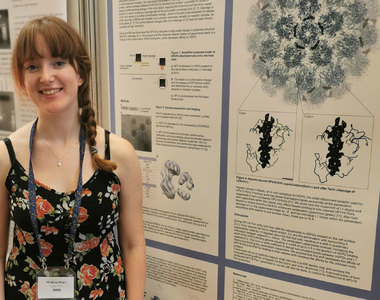

26 August 2021 | Story Thami Nkwanyane, Karin Lehmann. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 5 min.

Many South Africans are deprived of their right to decide who will inherit their estate when they die, a University of Cape Town (UCT) study has found.

Section 37C of the Pension Funds Act 24 of 1956 does so by removing death benefits from one’s estate and, therefore, from their testamentary control, and transfers the right and responsibility of allocating their death benefits to the trustees of retirement funds.

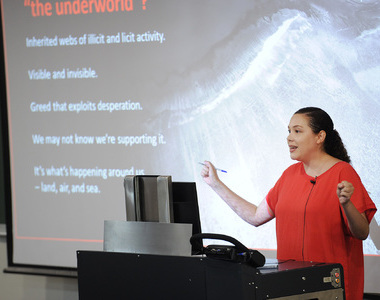

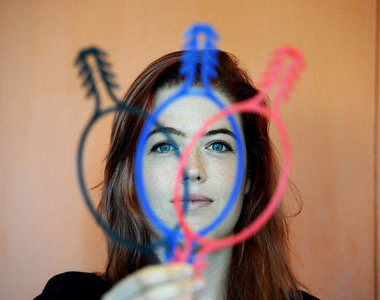

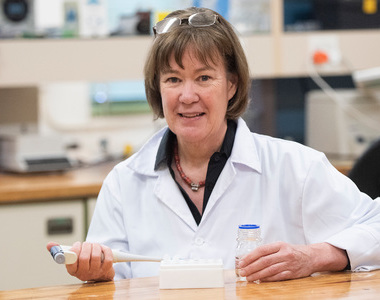

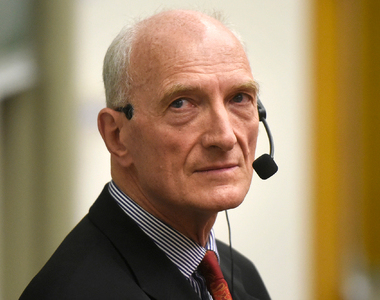

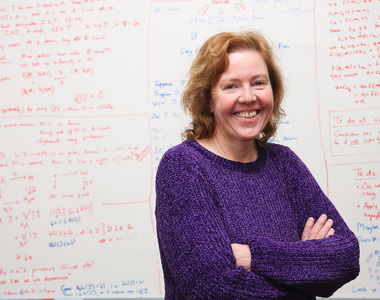

Karin Lehmann, a lecturer at UCT’s Department of Commercial Law, challenges this Act in her PhD thesis as being unconstitutional. She argues that most South Africans do not own substantial assets when they die; therefore, for most employed people, their retirement savings is the most valuable property they own, which means that they effectively do not have the right to select the recipients of their most valuable property.

“Many members, if they could somehow come back from the dead, would be disconcerted to discover that their wishes have not been followed.”

Lehmann has been a trustee of the UCT Retirement Fund for many years. It is in that capacity that she first became aware of Section 37C.

She said interpreting and applying the Act is not an easy task.

“This is important when one considers that trustees are usually lay persons, without legal expertise. They must first determine whether you are survived by any dependants. The Act contains an extensive definition of dependant, which requires that trustees understand and apply principles of Roman-Dutch law and customary law.

“The definition identifies the following people as dependants: spouses and children; any other person you were legally liable to maintain; any person you would have become legally liable to maintain in the future, had you not died; and, last but far from least, factual dependants,” she said.

Factual dependants

Although it is clear that spouses and children are dependants, determining whether someone is a spouse or a child can be surprisingly difficult. The Constitutional Court, for example, has stated that a second or subsequent customary marriage is invalid if the first spouse had not consented to it. Trustees cannot therefore simply accept documentary proof of a marriage at face value when the validity of the marriage is contested. Paternity disputes are also quite common, especially when a child was born outside a marriage.

Lehman states that the most problematic category, in her opinion, is that of factual dependant, who is any person the member was not legally liable to maintain but who was dependent upon the member for maintenance. This would include any person whose education you were helping to fund or any person whom you were helping pay for their basic living expenses, such as food, accommodation, clothing and medical care.

Co‑habiting partners are almost inevitably considered to be factual dependants, even if surviving partners are capable of supporting themselves. Where a member is survived by multiple dependants, or a combination of dependants and nominees, no dependant or nominee has a right to share in the benefit – whether and how much they ultimately receive depends on the discretion of the trustees. Although a member can nominate dependants, the term nominee is used to refer to nominated beneficiaries who do not qualify as dependants.

“Many members, if they could somehow come back from the dead, would be disconcerted to discover that their wishes have not been followed,” said Lehmann.

This may happen because they failed to complete a nomination form, perhaps believing that they had no dependants and that their death benefit would therefore be paid to their estate. It may also happen because the trustees overrode their wishes, which trustees frequently do.

The clear pattern is that a member’s wishes will frequently be overridden when the member is survived by a spouse or partner.

Urgent need for reform

Lehmann argues that the reason members’ wishes are so frequently overridden is attributable to the determinations handed down by the Adjudicator’s Office, which began operating in 1998. Adjudicators have repeatedly emphasised that members’ nomination forms are not binding on trustees, and that they serve as a guide only. Apart from the effect that the Act has on members’ testamentary freedom, its impact on spouses married in community of property can be devastating. It also takes away any right the surviving spouse would have had, under the law of marriage, to share in the death benefit. This is because Section 37C has been interpreted as superseding all other laws.

Trustees often reallocate the benefit among dependants, so some dependants remain vulnerable, or even worse off, than would have been the case had the member’s wishes been followed.

“There is a need to protect vulnerable dependants, but not by giving trustees such broad, unguided powers to override members’ wishes.”

“I am therefore of the view that Section 37C is unconstitutional, insofar as it unreasonably and unjustifiably limits both the member’s and surviving spouse’s (married in community of property) rights to property and dignity.

“There have been a number of recent cases in which the courts, including the Constitutional Court, have acknowledged that testamentary freedom is protected by both the constitutional right to property and the right to dignity. The prevailing view within academic circles and the retirement fund industry is nevertheless that Section 37C is constitutional,” said Lehmann.

She believes her research will persuasively demonstrate that Section 37C is not constitutional. She also hopes to demonstrate that Section 37C too often operates inequitably in practice, given its impact on excluded beneficiaries.

“There is a need to protect vulnerable dependants, but not by giving trustees such broad, unguided powers to override members’ wishes even when those wishes are reasonable, and not by depriving spouses of their proprietary rights. I believe Section 37C is in urgent need of reform,” she concluded.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.