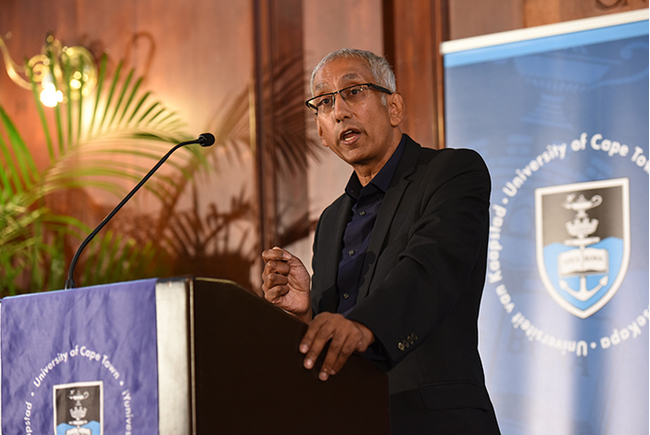

‘Ours is to educate, not to captivate’ – Yunus Ballim

27 August 2021 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Gallo Images/Sowetan/Antonio Muchave. Read time 10 min.Higher education is not intended to answer life’s big questions: ‘Who am I?’, ‘How should I live?’ or ‘What choices should I make?’ Rather, it must give context to these questions, developing students’ reasoning abilities in a world that is “complex and frighteningly ambiguous”, said Professor Yunus Ballim.

Professor Ballim was delivering the 55th TB Davie Memorial Lecture, hosted by UCT’s Academic Freedom Committee on 25 August. The annual lecture honours former UCT vice-chancellor Professor Thomas Benjamin Davie’s defence of the principles of academic freedom when these were under pressure from the apartheid government.

Ballim is from the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), and the founding Vice‑Chancellor of Sol Plaatje University in the Northern Cape.

Engaging with the unfamiliar

In his address, titled ‘Ours is to educate, not to captivate – teaching, learning and student development in a context of academic freedom’, Ballim argued that it is not the university’s role to make students captive to particular worldviews or forms of knowledge about the empirically observable world.

“But the principles of academic freedom also oblige a university to give expression to the liberating value of education, by being proactive about ensuring the students have opportunity to develop the knowledge, skills, and habits of mind that allow them to maintain a sceptical attitude towards received wisdom, and to be able to critically reflect on prejudice, dogma, misconception – both their own and those of others – in their living and working lives as graduates,” said Ballim.

He continued: “In the context of the liberating value of education, teaching means to enable our students to positively engage with the unfamiliar, while also helping them to see the familiar in unfamiliar ways – and encouraging them in sceptical attitudes towards all received knowledge, including the theories and hypotheses they receive from us.”

“Teaching means to enable our students to positively engage with the unfamiliar.”

Together with competent classroom teaching and functional learning facilities, students should also find a university that is open to different ways of knowing and is universal in its approach to “the world of ideas”.

To do this, universities must fully express the liberating value of education.

“This demands that we have freedom to decide who teaches, who learns, and what we teach – but it also requires that our students find an institution that is free from harmful learning experiences.”

But academic freedom should also shape the foundational values that guide a university’s processes, operations and internal relationships.

As such, the principles of academic freedom place numerous obligations on a university, particularly in its approach to students’ educational development and their expectations of their educational experience.

“And [students should also find] these values in the general operation of the university, as well as in the individual academics who teach our students.”

Freedoms and institutional culture

The principles of academic freedom should also permeate institutional culture, as expressed and experienced at three levels of engagement with the university.

The first layer lies in the physical landscape of a university and the care afforded it, which consciously or unconsciously creates a statement about the institution’s values, he said.

“[It] acknowledges the state of the buildings, the neatness of the gardens, the posters on the walls that make statements about institutional values, or [that] carry invitations to lectures, art events, or protest meetings.

“Those who have visited under‑resourced or otherwise troubled universities will recognise how important this first-layer view is in formulating our judgment about the general operation, [and] operational and academic culture, of such an institution.”

The second layer relates to the formal regulation of the relationships between the different sectors of the internal university community: the academic, human resources and operational rules and policy statements, and the ways in which these regulate the power and authority of relationships across the institution.

“These rules also describe the requirements and processes for accountability by staff and students: whether you will be called out for smoking in the hallway, or playing your music too loudly in the residence, or how academics are to account for the study performance of the students in the classes.”

“Trying to pin down these meta rules is much like the proverbial attempt at nailing one’s porridge to the wall.”

But the third and most important layer, said Ballim, is the complex network of unwritten rules that direct individuals and committees into making choices, while creating the illusion that those choices were rationally or freely made.

“These are meta rules that make up the habits of an institution, society or a community, including things like the rules for what is to be taken as polite behaviour. Trying to pin down these meta rules is much like the proverbial attempt at nailing one’s porridge to the wall; you feel its effects, positive or negative, without being able to point exactly to the thing or the behaviour that stimulated your feeling.”

The way we do things here

Citing an example, Ballim said that early in his university career, in 1994, he was thrust into academic administration as assistant dean for undergraduate admissions at a Johannesburg university. Here, he became aware of the entrenched “way we do things”.

These unwritten rules became infused into the psyche of middle-level academic administrators and administrative staff at the faculty level – so deeply, he said, that it automated their choices on matters of practice and strategy.

“This, in itself, is not a bad thing. It is good that our students leave us with a distinctive flavour of what it means to be a UCT or a Wits or a UWC graduate. And this flavour will include the particular habits of mind and values that the university develops in its graduates.

“But ensuring that the impact of this flavour is always positive demands an acute awareness – particularly on the part of leadership, at all levels of the university – of the nature of this complex network of informal rules, and the need to consciously and continually direct and shape its character,” he said.

And this is guided by habits and patterns of exclusion based on identity, creating a network of unwritten rules for normative behaviour over time.

Whole graduates

This was well illustrated by the infamous Reitz incident at the University of the Free State in 2008, said Ballim, which led to the Soudien Report on discrimination in South African universities.

But the primary offensiveness of the incident was not its illustration of racism, Ballim noted.

“Rather, it was offensive because the students involved were close to completing their studies and graduating. A student who is academically successful and graduates from the university with such social attitudes may have been well trained, but was certainly under‑educated. And my sense is that such students have possibly forfeited the right to call themselves graduates.”

More importantly, he said, the institution had failed in its duty to properly educate its students, and needed to be accountable.

That responsibility should have ensured that its students would find “sufficient opportunity to test and reflect on these prejudices and leave the university as successful graduates, having had an opportunity to see the world through the eyes of the other”.

Collective responsibility

Eliminating these institutional pathologies requires specialist attention, time and remedial treatment.

“Sometimes these habits may be well intentioned, but they have seriously hurtful consequences, such as that most corrosive form of racism that expects less from people considered as ‘the other’; and is at pains sometimes to apologise for poor behaviour or poor performance on the basis of their blackness, or their ‘townshipness’ or their poorness.

“We should rather aim for the university to be a microcosm of what society could be like.”

“The fact that our staff and students arrive with prior socialisation that includes these pathologies of behaviour is not a reason for their continued existence in our institutional cultures. We must resist the paralysing argument that I often hear that the university is a microcosm of its society. We should rather aim for the university to be a microcosm of what society could be like. We should set the tone as we speak to our public.”

While it is not always possible to make an argument for collective guilt, as in the case of racism or oppression, it is possible to make an argument for collective responsibility, he said.

Academic freedom is also directly reflected in the construction of curricula, and in the teaching and learning experience.

“Teaching is the front end of our task in engaging with the process of education – as a liberating experience for the next generations of intellectuals, who will do better, [and] see differently, and much further than we did. I’ve long held the belief … that the teaching space, and the relationship between those who wish to teach and those who wish to learn, is a sacred space.”

Part of the academic freedom project also relates to decolonising the university. This, Ballim said, was better framed around the task of what Kenyan writer and academic Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o described as “decolonising minds”.

“It is here that the university can make its most significant contribution to its public through the educational development of graduates who will stretch the front end of human endeavour, with warm hearts and with fine minds. And who are always awake to the big questions of human suffering, environmental sustainability, and the relationships between power and powerlessness.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

TB Davie Memorial Lectures

In the classic expression of freedom of speech and assembly, UCT's policy is that our members will enjoy freedom to explore ideas, to express these and to assemble peacefully.

The annual TB Davie Memorial Lecture on academic freedom was established by UCT students to commemorate the work of Thomas Benjamin Davie, vice-chancellor of the university from 1948 to 1955 and a defender of the principles of academic freedom.

Organised by the Academic Freedom Committee, the lecture is delivered by distinguished speakers who are invited to speak on a theme related to academic and human freedom.