Mamdani returns

24 August 2017 | Story Yusuf Omar. Photos Caroline Bull. Video Saadiq Behardien.

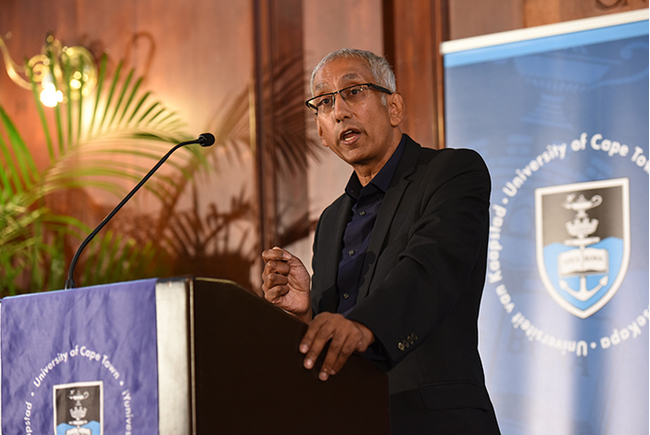

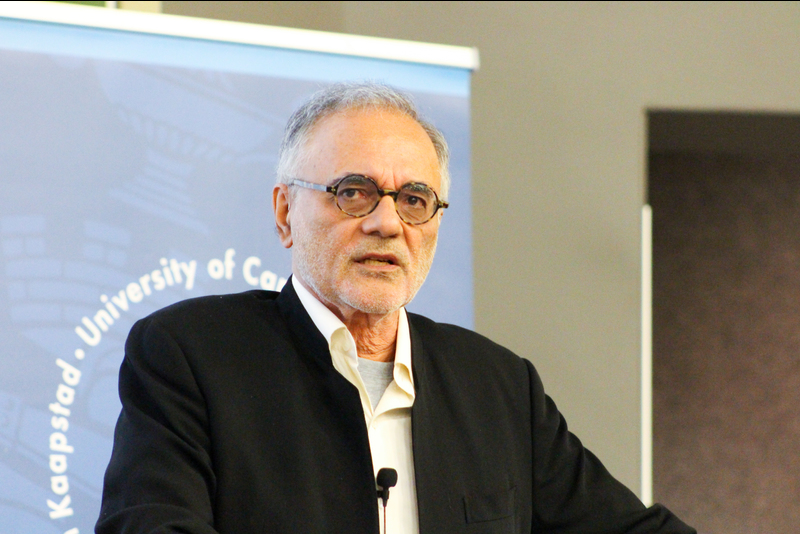

Professor Mahmood Mamdani takes a deep breath before he begins. He is here to deliver a lecture called 'Decolonising the postcolonial university', on the platform of the 2017 TB Davie Memorial Lecture on 22 August, which commemorates the former vice-chancellor of that name who championed academic freedom. It is a poignant moment, given Mamdani’s own history with UCT and academic freedom.

Mamdani was appointed director of the Centre of African Studies at UCT in 1996. But he was to leave only three years later, after heated disagreements with colleagues who refused to accept his Problematising Africa curriculum which foregrounded African scholars hitherto unheralded in South Africa’s postcolonial academy. Suspended from teaching, Mamdani left for Columbia University. That seismic moment became known as the Mamdani Affair, and he had not returned to UCT until now.

Moments before he addressed the audience, some students and staff greeted the decolonisation doyen with a rendition of Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika, more struggle songs and representations by formerly outsourced workers.

“The discourse of decolonisation cannot happen in a vacuum,” student Thabang Bhili offered an explanation for the unannounced interlude.

An expectant hush while Mamdani was preparing his notes was broken by a sheepish voice from the audience: “We apologise to you.”

Laughter and clapping ensued, and more laughter followed when another voice chipped in: “We are very sorry about it.”

Mamdani, apparently, saw no need for sorrow.

“I am overwhelmed by this welcome,” he began. “I hope we can have a discussion which justifies it.”

The energy in the audience was a signal that this was hardly a traditional lecture, where the audience waits politely until afterwards to express its delight or indifference. Perhaps it was the cocktail of the subject matter, the occasion and the speaker, but Mamdani had his audience engrossed and frequently interjecting with murmurs, nods and sometimes more.

A day before the lecture, someone had asked Mamdani why, after staying away from UCT for 16 years, he had decided to come back now.

“I said: because Rhodes fell.”

Again, whooping and clapping.

“To me it was a signal that a process of change was in the offing, and I would be the last person to stay away.”

“[Rhodes falling] was a signal that a process of change was in the offing, and I would be the last person to stay away.”

This was a talk that swirled through a history of how European expansion inflicted upon the conquered the imperative to classify all things; of brilliant quips of what colonialism actually was and what decolonising a university – and indeed a continent – truly means; and told of an epoch-shaping battle between activist-academics Ali Mazrui and Walter Rodney that would lay the groundwork for what we today understand as a public intellectual; and arguments of how it was easier to change one’s creed than to undo the idiom of one’s thought.

It was a lesson in what Mamdani has preached since his time at UCT– studying Africa through the eyes of Africans instead of only through the lens of Europeans. In this, he referenced a wealth of African scholars through the ages into his talk, from Ibn Khaldun in ancient times to this generation’s Kwesi Kwaa Prah.

The university as a colonial project

“The African university began as a colonial project, a top-down modernist project whose ambition was the conquest of society,” Mamdani summarised. “The university was in the frontline of the colonial civilising mission.”

Properly understood, this civilising mission was the precursor to the structural adjustment programme and the World Bank and IMF loans that enforced conservative economic policy on indebted, newly independent economies.

“The university was the original structural adjustment programme,” he said.

“The African university began as a colonial project, a top-down modernist project whose ambition was the conquest of society.”

Classification became global with European expansion, said Mamdani. Household-name sociologists like Emile Durkheim and Karl Marx all used a form of classification for their theories – Durkheim chose chemistry and Marx biology.

“For those who did the classifying around the world, their reference point was the West – the world they knew.”

It wasn’t easy to unlearn one’s assumptions, but, as Mamdani put it, one could be conscious of them and thus be modest with one’s claims.

With the university now understood as an outpost of the colonial frontier, whose mission was to subjugate the natives and enforce the colonisers’ way of life on the land, Mamdani had a message for those who found themselves in such a space: “Your task has to be one of subverting that mission from within.”

It’s about the unknown unknowns

Mamdani used the “spirited exchange” between Mazrui and Rodney, of Makerere University and the University of Dar es Salaam, respectively, to make a salient point.

Mazrui, in coining the concept of “mode of reasoning”, argued that “compared to political inculturation, ideological orientation is both superficial and changeable. To be in favour of this and that country, to be attracted to this system of values rather than that, all are forms of ideological inversion.

“Under a strong impulse one can change one’s creed, but it is much more difficult to change the process of reasoning which one acquires from one’s total educational background.”

“Under a strong impulse one can change one’s creed, but it is much more difficult to change the process of reasoning which one acquires from one’s total educational background.”

As proof, Mamdani related, Mazrui argued that no amount of radicalism in a Western-trained theorist could eliminate the Western style of analysis he [or she] acquired.

“After all, French Marxists are still French in their intellectual style,” Mamdani said to a chuckling crowd.

Is there a mode of reasoning we can term African?

Mamdani’s answer, to the audience’s discomfort, was no.

One of the reasons was that most Africans had emerged from colonialism speaking many different languages. Some estimates were of around 700 African languages. But only Afrikaans, which ironically was first written by slaves in Arabic script, ever developed into an academic mode of instruction.

“Colonialism cut short [the] possibility of cultivating an intellectual tradition in the languages of the colonies,” said Mamdani. “As a result, our home languages remain folkloric, shut out of the worlds of science, learning, high culture and government.”

European languages have retained that pedestal.

Even kiSwahili, which is an exception to the folkloric trend, is treated as a “foreign language” at university level.

Mamdani challenged the university leadership to open a centre for the study of Nguni languages and knowledge traditions.

“Study the literature in the language and develop the literature in the language."

Moreover, the university needed to invest in scholars who could study and teach the non-Western traditions.

“Theory cannot be developed without reference points,” said Mamdani, imploring that we need new reference points.

“Give up the obsessing with comparing with the West. The world is larger than we have known.”

A personal reflection

Mamdani’s lecture traversed too large a ground for this limited space (and watching the full video recording is recommended), but he did reserve time for a “personal reflection”.

“I came here in 1996 full of excitement, wanting to learn and contribute to the making of a new world. Instead I found a world very unsure of itself; full of anxieties. The leadership of government had changed, but the leadership of institutions had not.

“Instead of being receptive to change, the institutional leadership looked with distrust to every initiative for change, suspecting it of harbouring a hidden, subversive agenda. It felt lonely. In retrospect, though, it was a great learning experience. It was first at the University of Dar es Salaam, which was my first academic job, but then at UCT that I began to think of what it would mean to decolonise a university. For that opportunity, I am thankful to this university.”

A spirited discussion with audience following the lecture, after which Mamdani closed with a parting shot of wisdom: “The best scholarship is done in times of intense activism. Now that you are active: read!”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

TB Davie Memorial Lectures

In the classic expression of freedom of speech and assembly, UCT's policy is that our members will enjoy freedom to explore ideas, to express these and to assemble peacefully.

The annual TB Davie Memorial Lecture on academic freedom was established by UCT students to commemorate the work of Thomas Benjamin Davie, vice-chancellor of the university from 1948 to 1955 and a defender of the principles of academic freedom.

Organised by the Academic Freedom Committee, the lecture is delivered by distinguished speakers who are invited to speak on a theme related to academic and human freedom.