Mismatch between employability assumptions, lived realities

30 December 2025 | Story Kamva Somdyala. Photo Supplied.

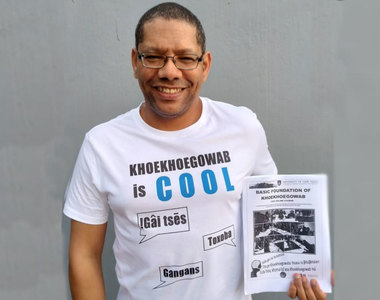

The University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Graduate School of Business’ (GSB) alumnus Natasha Haffajee presented her team’s research titled, “Unconventional Paths” at the recently held Reach Alliance 2025 Conference in Singapore.

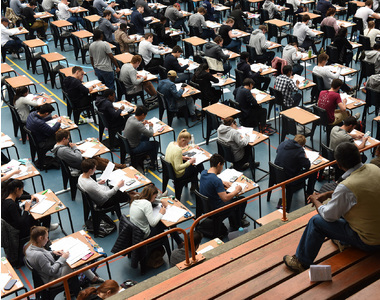

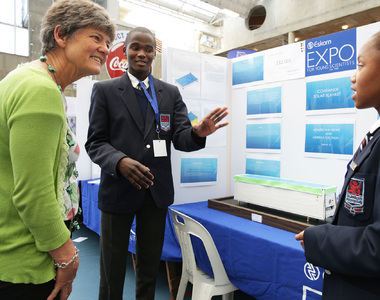

The research explores innovative and community-based approaches to addressing youth unemployment, particularly among young people without high school qualifications. The research, conducted in collaboration with team members, Wenbo Zheng and Sikelelwe Mtshizana, forms part of the global Reach Alliance initiative – an interdisciplinary network dedicated to investigating how to deliver essential services and opportunities to underserved populations.

The Reach Alliance brings together leading universities from around the world, providing a platform for young researchers to translate academic inquiry into actionable solutions for global development challenges. With South Africa’s youth aged 15–24 and 25–34 having the highest unemployment rates in the country (58.5% and 38.4% respectively), it is little wonder why such a topic emerged during discussions.

“My work sits at the messy intersection of youth transitions, place, and inequality – especially in underserved parts of South Africa. I am deeply interested in the everyday ingenuity that people bring to survival and progress: the “make a plan” spirit; the informal hustles that hold households together; and the determination young people show even when the odds are stacked,” said Haffajee.

Kamva Somdyala (KS): Tell us a bit about yourself.

Natasha Haffajee (NH): For most of my career I have worked in the people and culture space, building pathways into training and work, and helping organisations become places where young people can genuinely grow. Over time, I became increasingly interested in the mismatch between institutional assumptions about employability and the lived realities of young people navigating constrained labour markets.

KS: How did your team’s research come about?

NH: “Unconventional Paths” emerged from a shared concern that too many youth-focused employment conversations start and end with formal qualifications, as if that is the only legitimate proxy for potential. In South Africa, high school completion is often treated as a non-negotiable threshold for employability, even in entry level roles, which we believe to be tone-deaf to the realities of our country. In many communities, young people who did not complete high school are already working, contributing, learning, and adapting – just outside what our systems formally recognise. We wanted to develop an understanding of how they navigate their realities – not to tell a pity story, nor a story of “success against all odds” – but as real pathways shaped by constraints, plans, setbacks, and difficult choices.

KS: What does delivering essential services and opportunities to underserved populations look like?

“The route starts with trust and proximity, because in many communities the real infrastructure is human: a mentor, a youth worker, a coach, a neighbour.”

NH: In under-resourced contexts, the most reliable “route” is often built from the ground up, shaped by communities themselves, who already understand the terrain, the risks, and what it takes to keep going. So the route starts with trust and proximity, because in many communities the real infrastructure is human: a mentor, a youth worker, a coach, a neighbour who knows which door to knock on, how to speak the language of institutions, and who see the constraints early, that are often invisible to outsiders: taxi fare, data costs, device access, documentation, safety, caregiving responsibilities, and the administrative load behind every application.

KS: Please share your experience of the conference.

NH: What I valued most was the emphasis on practical usefulness. The conference pushed us to communicate findings in a way that reduces the burden on decision makers, by being explicit about why findings matter and how they can be used. It also reinforced the importance of humility in research, because communities are already solving problems daily, and our job is often to make those strategies visible and investable. On a personal level, it was affirming to bring a South African case into that space.

KS: The theme seems to be a double-edged sword: a crisis of youth unemployment generally, then you add ‘without high school qualifications’. How does that conversation begin and how does it flow?

“What other signals of potential can we recognise, and what support can help young people translate informal experience into credible proof of skill?"

NH: In South Africa, educational attainment is often treated as a moral marker. The moment you frame the issue poorly, the conversation collapses into stereotypes, and the structural realities disappear. So, we start with context. Many young people do not leave school casually. They are pushed out by family instability, schooling disruptions, insecurity, transport costs, missing documentation, or a system that does not consistently catch learners when they begin to fall behind. From there, the conversation shifts to what happens next. The conversation becomes constructive when we ask: what other signals of potential can we recognise, and what support can help young people translate informal experience into credible proof of skill? How do we widen entry points without lowering standards? And how do programmes and employers collaborate so that a first opportunity serves as a bridge into stability?

Haffajee hopes to build on this work through further research on youth transitions and the conditions that make opportunity reachable. It is also her desire to keep translating findings into tools and practice, and support current and future UCT Reach teams to produce research that is rigorous, ethical, and genuinely usable.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.