AI, authorship and authority

29 August 2025 | Story Kamva Somdyala. Photo iStock. Read time 4 min.

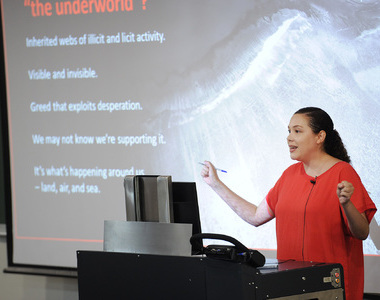

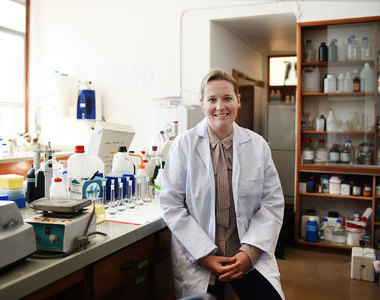

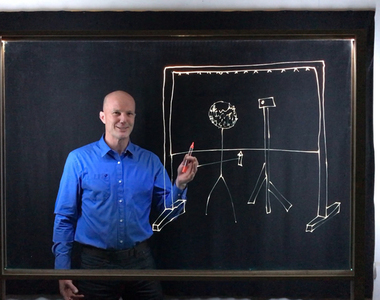

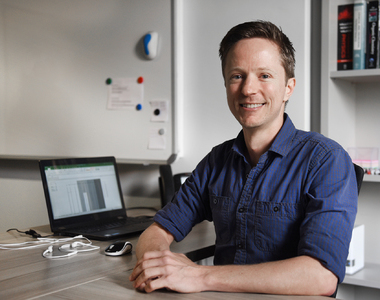

With the accelerating pace of generative artificial intelligence (AI) commonplace, educators are being intentional about its presence in academia. One such professor is Dr Aditi Hunma, a senior lecturer in the Language Development Group (LDG) in the Centre for Higher Education Development (CHED) at the University of Cape Town (UCT).

There is widespread acceptance across several sectors about AI’s risks; however, scholars and users of AI want people to see it as having a rapport with the user: the human. UCT has done its bit in addressing AI, like providing a set of overarching principles for ethical and responsible use, through the AI in Education Framework.

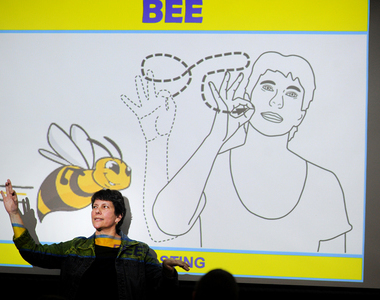

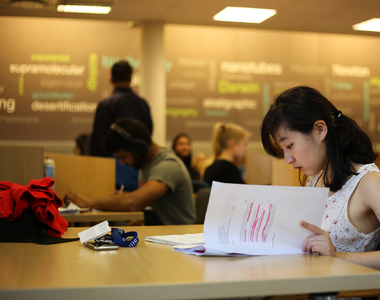

During a lecture, Dr Hunma demonstrated using a writing exercise with students to understand their appetite for AI. She shared key considerations, such as what writing [with AI] looks like; being alert about whose voice is amplified [in the text] and how to harness the tool’s critical thinking ability. “Use it ethically and let it enhance your skill rather than rob you of your agency,” she said. A part of the exercise was analysing two essays, comment on the quality, give it a mark out of 10, and then discuss successes and shortcomings of the two pieces of writing before identifying one written through AI, and one that was not.

At the end of the exercise, students were unanimous in not only scoring it low but also picking one done using AI. It was the right segway for Hunma to introduce the concept of voice or writer identities. Said Hunma: “There are three ways to look at this. [The first is] discipline-specific self (following the rules), where you can structure the essay like a historian/sociologist and presenting content from the discipline. The second is the autobiographical self, where a person brings in their own subjectivity. The third is critically engaging with the content and, in some cases, taking a position and defending or supporting it.”

With all these in mind, which one is replaceable by the machine?

“Whose thoughts, ideologies and biases are being reproduced in our essays?”

Within AI, there is also the contestation of authorship and authority. “It’s a place where you are wishing to retain authorship, but giving AI authority over our thoughts,” explained Hunma. This leads to curious thoughts around decolonisation. “Whose thoughts, ideologies and biases are being reproduced in our essays?”

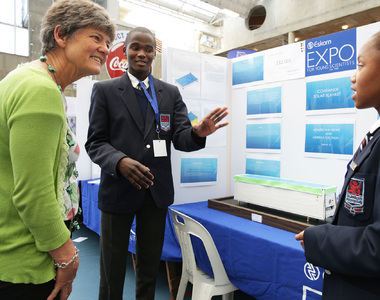

One of the major talking points from a UCT perspective is doing away with detection tools. The institution has also hosted an AI symposium looking at assessment practices where delegates discussed how to consciously move towards reframing assessment practices to better align with authentic learning, critical thinking, and ethical engagement in an AI-mediated world. The UCT AI in Education Frameworks also noted that some key messages from the consultations were to foreground academic integrity practices, ensure equity for staff and students in accessing AI technologies in teaching and learning, and promote staff and student AI literacies and capabilities.

Academic guide

While students may be left to their devices with AI, there is still a “use and abuse” factor that can be attached to it, explained Hunma. “Beware of oversharing on AI platforms because personal data becomes public data.

“Finally, to fully integrate it into your space, the use of AI must act as an academic guide which generates examples and scenarios that help with concept understanding. It must promote critical reading practices. It must act as an opponent in a debate and as a quiz-maker and mock assessor.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.