The argument for compulsory high-school history

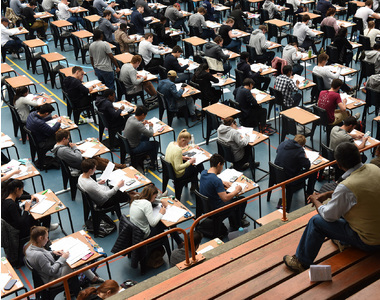

16 November 2018 | Story June Bam. Photo Sue, Flickr. Read time 10 min.

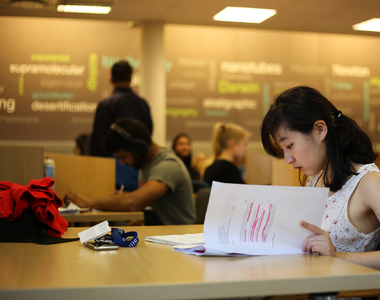

The current debate on the Schools History Ministerial Task Team’s (MTT) recommendation for history to be compulsory in grades 10 to 12 in schools from 2023 needs to be historicised.

Instead of shooting down the MTT’s report’s recommendations, I want to affirm and consolidate the context within which this report has been produced. To do this, a brief historical overview of the last 25 years of the “history in schools” debate’ is needed.

The neglect of school history in education policy shortly after 1994 came as a surprise for two reasons. First, it was not within the long history of the black oppositional historiographical tradition or within the People’s Education Movement of the 1980s to side-line school history.

The ANC school in Tanzania, which called then for an “interdisciplinary approach” in history education, argued that South African history should be placed within the regional history of southern Africa and within the context of world history.

Although Unity Movement historiography emphasised what they called “the intercontinental modal struggle” (a world history approach to the precolonial), the ANC research report argued for a “precolonial history that acquires a particular importance as does African history”.

Although black political movements against apartheid were ideologically at loggerheads, they shared a common vision for the non-negotiables in a decolonised education programme. History as compulsory was a minimum in a critical pedagogy to ensure a critical citizenry. The ANC schools crafted a vision for a new history in the camps and exile while Unity Movement intellectuals did so in community halls.

My argument is about context. To illustrate, I start in 1991, almost 20 years after the ANC research report, when not only capital and land were negotiated but also education. I recall a schools history conference that was held in Katberg in the Eastern Cape, of which the outcome was the envisaged place and role of history in the new South Africa, in a publication titled History Matters.

These school history debates before 1994 brought together the racialised education departments with the majority of delegates often drawn from the then white House of Assembly. Participants came from different apartheid education realities that informed how they saw a new history education philosophy for South Africa. But the dominant voices in the debates remained the white middle class supported by strong publishing networks.

Exciting, innovative teaching materials, like those of R Pienaar and M Robinson (1992), Our Community in Our Classrooms, were unsurprisingly marginalised. These African historiographies and Africanised perspectives on history education in South Africa have always been pushed to the margins in the “official” debate. Communities from these historiographies were never really lead participants in the public “official” debates.

In about 2000, Kader Asmal, as minister of education, appointed novelist and former vice-chancellor of the University of Cape Town Professor Njabulo Ndebele to chair the first History and Archaeology Report. That intercession signalled an essential tactical shift from the very dominant British philosophies of school history. In June 2001, the South African History Project (SAHP) was established as a direct result of the report.

The main objectives of the project included establishing the recording of oral histories, strengthening teacher training and encouraging history researchers and scholars to write new history textbooks.

By 2001, provincial oral history projects were established, a national research audit on history textbooks had been conducted, and a national register of historians and archaeologists was created. The textbook audit indicated that there were good new textbooks available, but teachers were not adequately trained to use them.

In collaboration with the South Africa Democracy Education Trust, South African History Online, universities, museums, community historians and libraries, about 1 300 lead history teachers were trained in oral history. Intended as catalytic interventions only, they were to be followed up with sustainable long-term provincial training programmes. Historians, archaeologists, literary scholars, archivists, librarians, linguists and teacher trainers were to play central roles in these plans.

The SAHP ended in 2004 with Asmal’s departure as minister and plans were put in place by the national education department for the systematic implementation of the teacher training programmes starting in 2005. This was to include the distribution of learning and teaching materials to all schools. An entire curriculum review process subsequently took place and the curriculum assessment policy statements (Caps) was implemented.

One of the concerns raised by the #RhodesMustFall student movement, a decade later in 2015, has been the relative absence of African history in schools. The MTT had their reference point in the same year as the “continuity” with the work of the SAHP and those of the University of the Witwatersrand History Workshop teacher development team. More notably, also, is that about 50% of the members of the SAHP participated in the MTT process.

The MTT’s main critique of the lack of preparedness of teachers is that Caps content is organised in such a way that South Africa has been separated from African history and the world; that key concepts in oral tradition are lacking as African historiography needs to be strengthened with interdisciplinary approaches.

The report cautions that not any teacher can be assumed to be able to teach history; that the skills required should include extrapolation and judgment; taking arguments through evidence to a logical conclusion; the importance of “conceptual understanding”; “depth of content” and the importance of a literary culture.

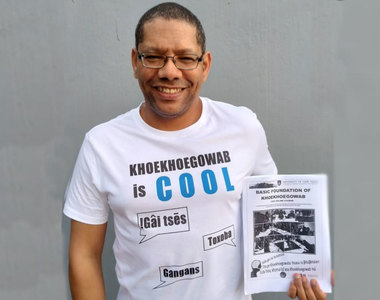

It argues that we need to think about Africa and history differently and to emphasise the key place of gender and African oral traditions in teaching precolonial history; that it was important to recognise the work of Cheikh Anta Diop and Toyin Falola on the “ritual archive”; and that Khoisan history has to be treated with greatly increased historiographical depth through Khoisan linguistic frameworks and the study of rock paintings.

The report also highlights the colonial distortion of Khoi and San identities (now also deeply contested terms). Ideologies aside, these recommendations are clearly in line with a long tradition of black oppositional historiography.

Therefore, if the national debate aired on July 16 this year on Prontuit is anything to go by, then it is burdened with deterministic arguments that are not helpful. The stance that the compulsory recommendation is for ideological reasons in the way that the apartheid regime brought in Afrikaner nationalist history obfuscates the key “decolonial” moment we have in this debate.

It was always deeply problematic to assume that a British philosophy of history education can be rigidly applied in an African context. Way back in 1991, history scholar Matome Mokgagabone reminded us that our Eurocentric conceptual frameworks no longer hold for the majority. We need to reframe the debate. How can African-rooted scholarship help us to rephilosophise school history and help to inform our appraisal of the compulsory recommendation?

It is in recognition of this African epistemological contextuality that I find it disingenuous to suggest that the MTT report on history education is carrying out a propaganda intervention for the ANC. I am saying this as someone who has always engaged critically with ANC policies, even when it was not fashionable to do so.

We need materials rooted in African languages, new approaches to periodisation, new conceptual frameworks that break us free from colonially established canons and disciplines.

Most teachers are African and have intergenerational knowledge forms that are not recognised in these “canons”, but that are invaluable for history education training.

We are called upon to take up the challenge of multilingualism that Neville Alexander put forward in 1992 and in his many other writings. For instance, if lead history teachers in South Africa were expected to teach in a black African language, many would most probably fail as “experts”. A teacher training programme would look very different and perhaps much more accessible.

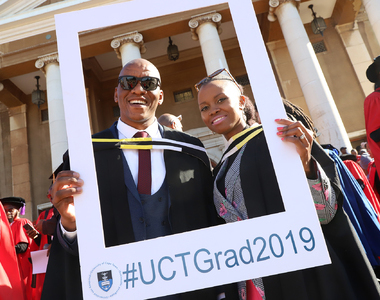

The Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town is one of those spaces where interdisciplinary teacher training can be supported by community knowledge production partnerships (already established). It is here where we engage in post-graduate interdisciplinary courses such as on problematising the study of Africa.

Therefore, we should appraise the anomalous arguments in the debate, because these prevailing voices are like the proverbial fish out of water.

Dr Bam is at the Centre for African Studies at UCT and is a visiting professor with Stanford University. She is former director of the South African History Project.