Time for a new kind of learning

25 January 2019 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photo Je’nine May. Read time 6 min.

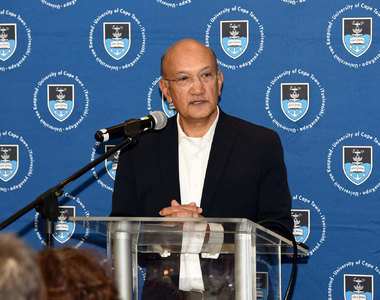

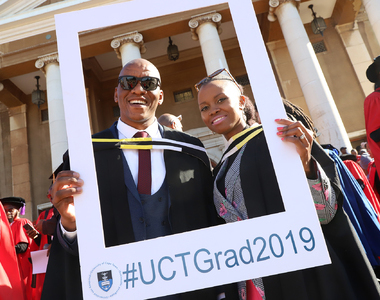

“It’s no longer what you know … it’s about what you do with that knowledge,” Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town (UCT), said during a panel discussion at the World Economic Forum (WEF) Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland, on Friday, 25 January.

Phakeng was among four speakers examining the topic: “A New Kind of Learning?”. Her co-panellists were Andria Zafirakou, who recently won the Global Teacher Prize 2018 as the “worldʼs best teacher”, Lego Foundation chief executive officer John Goodwin, and founder of code.org Hadi Partovi. Justine Cassell, a roboticist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), chaired the panel.

The question put to the speakers was, “What values, behaviours and skills must be taught to the new generation so they become responsible citizens in life and work?”

Phakeng, opening the discussion, said that for her the need for a new kind of learning predated talk about the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Remembering her time teaching mathematics, she said she had constantly grappled with the impact of technology and automation on her teaching and assessment. With the introduction of and easier access to calculators, memorising multiplication tables and drawing parabolas became irrelevant.

She asked herself why she was teaching her students these skills when they could find the answer at the touch of a button.

“What is the skill we are teaching them beyond just the knowledge of being able to do factorisation… what else is it that you are doing?”

These were the kinds of questions the basic education sector and tertiary institutions will have to ask themselves if they want to prepare students for the rapid changes of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Phakeng argued.

Collaboration

Asking the right questions must also be coupled with teaching, as well as encouraging the capacities that make us human.

Phakeng and her fellow panellists called for a move away from rote learning and memorisation, towards capacity building and focusing on uniquely human experiences and emotions. Included in these concepts is collaboration and problem-solving.

“Understanding the inequity of knowledge... itʼs going to be key.”

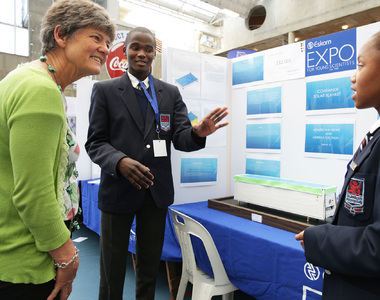

They agreed that the capacity to problem-solve is undoubtedly a necessity for dealing with the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The rapid changes will demand from young people the ability to rise above the immediate challenges and imagine the future.

“People collaborate, that’s how we problem-solve,” Phakeng said.

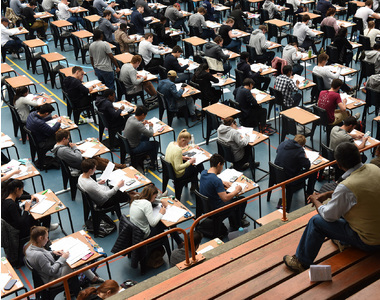

However, collaboration is often discouraged in learning environments where the emphasis is on individual work. Also, the sharing of ideas and answers can be perceived as cheating.

Phakeng referred to something she had previously discussed with colleagues: During exams, students are seated at individual desks. In the past, they were instructed to set their books aside during the examination. Then it was phones that needed to be set aside. Soon it will be watches, glasses, perhaps even buttons.

“We aren’t solving the right issue,” she said, suggesting what is instead needed is a reimagining of the learning and assessment environment that better prepares the student for collaboration in the work environment.

Cut and paste

Phakeng recalled an exercise that she did during one of her maths classes. To challenge the perception that knowledge is gained only through memorisation and duplication, she held an open-book test for the class.

“They were amazed; they thought I was the most generous teacher,” she joked.

But, when the students tried tackling the first problem Phakeng had set, their books were of no use.

“The book wasn’t helpful because it wasn’t a ‘cut and paste’ of the problem… you had to think more.”

The type of knowledge that she challenged during the open-book test holds people back from success in the workplace. Currently, students are taught, they reproduce what they’ve learnt, they get their certificate and they land a job. But when tasked with problem-solving in the workplace, they are ill-prepared.

“We are going to have to rethink what is this learning, why do we do it and for what.”

“We are going to have to rethink what is this learning, why do we do it and for what.”

Navigating knowledge

Knowledge, Phakeng said, “is accessible anywhere”.

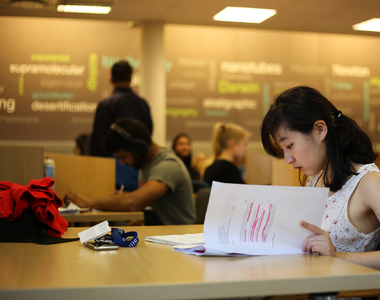

And the first-year students who have enrolled for the 2019 academic year at UCT will be inundated with knowledge.

She spoke of her upcoming welcome address at Parents’ Orientation and how she is acutely aware of the different kinds of knowledge with which students will be confronted. This will include opposing political messages and pseudoscience.

“Understanding the inequity of knowledge... itʼs going to be key.

“So, what is it that I need to tell them that is going to sharpen their ethical scrutiny?”

The ability to navigate these different kinds of knowledge, to know what to use and what to throw out, is part of what makes empathetic, responsible students and citizens.

The inability to navigate and scrutinise, said Phakeng, is contributing to “bringing our world to its knees”.

“It’s the what, the why, the how… For me, all of that is important in what makes us human.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.