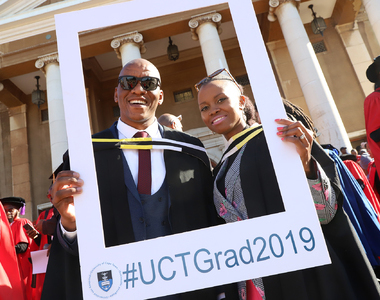

First cohort graduates in Applied Complexity Science

10 August 2023 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 7 min.

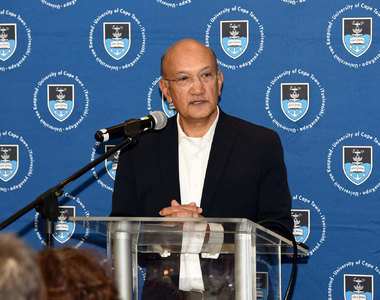

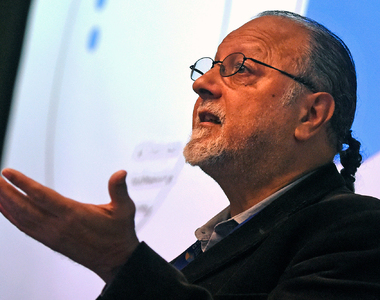

The complexity underpinning the world’s wicked problems calls for urgent collaboration between experts in different fields, as well as policymakers, researchers and civil society. University of Cape Town (UCT) Vice-Chancellor interim Emeritus Professor Daya Reddy was speaking at the July graduation ceremony for the first cohort in Applied Complexity Science.

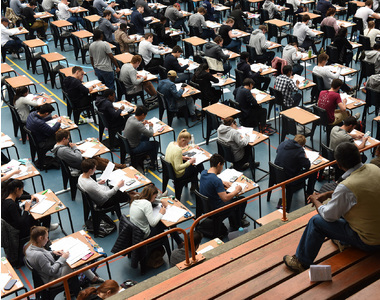

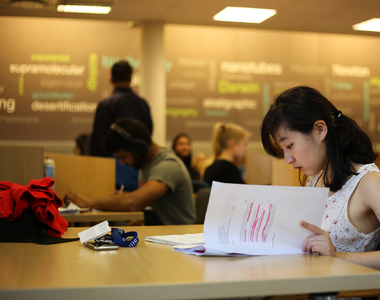

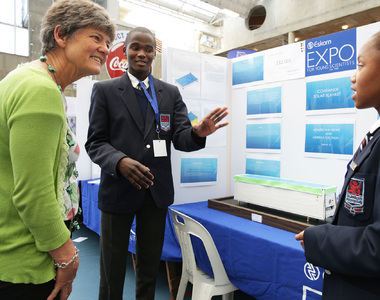

The graduates are staff from the City of Cape Town’s Department of Infrastructure.

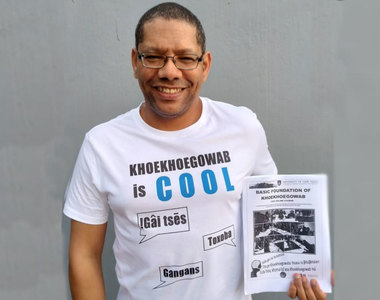

The postgraduate self-learning course was launched by UCT’s Centre for Extra-Mural Studies (EMS) in October 2021. It is convened by Dr Fuad Udemans, who has a PhD in Complexity Science from the UCT Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB).

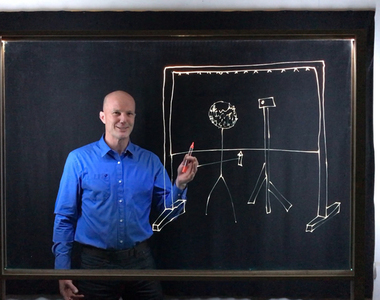

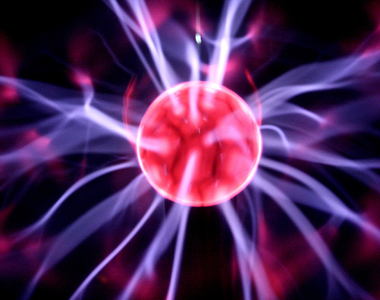

Complexity or systemic sciences offers an integrated scientific framework to understand and manage different systems. These are: simple systems (one that has a single path to a single answer); complex systems (composed of many components that interact, such as global climate); and chaotic systems (like the weather). Complexity studies focus on underlying patterns, interconnectedness, constant feedback loops, repetition, and self-organisation.

The cutting-edge course presents a new way of learning and thinking about these wicked problems, for example, the intractable climate change and persisting global inequality that threaten humanity. Its development is part of the innovation culture that is linked to UCT’s Vision 2030 and its mission of unleashing human potential, said Emeritus Professor Reddy.

Economist Adam Toose referred to these multi-crises, often inter-related and simultaneous, as “polycrisis”.

“Rather than trying to confront crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change on their own, we have to acknowledge that these crises interact with one another, influence one another and we can’t possibly succeed in addressing any one of these on their own.”

Societies and education institutions must change the way we approach them, said Reddy.

“Whether you are a scientist or an accountant, these crises need multidisciplinary approaches and perspectives.”

Adding to these challenges are the extremely rapid technological developments; the digital revolution, developments in artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning and their impact on humanity, said Reddy.

“They come with huge benefits in their ability to help us solve problems, but they come with huge risks too.”

Solutions must be co-created, he said.

“You start together in defining the problem and execute the plan together. This makes for wonderful new ways of working. But sometimes you have to hold on tight as you go.”

Reddy said that the Applied Complexity Science course had taken graduates to the next level of unleashing their potential as changemakers in a complex world.

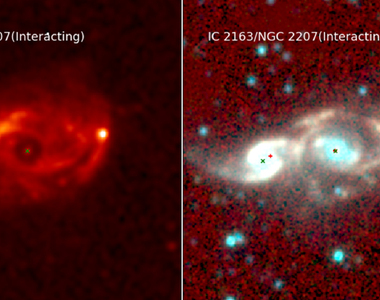

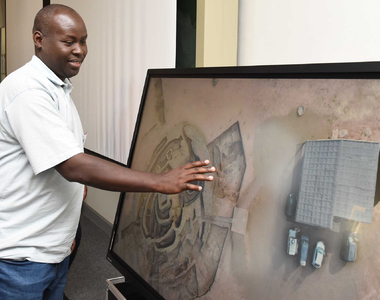

Speaking at the ceremony, Nazeer Rahbeeni, Director: Infrastructure Policies & Strategies in the Western Cape Government’s Department of Transport & Public Works, said his team had grappled with making connections between the course’s 18 disparate niche research areas. These are: AI, cartography, chaos theory, cognition, complexity, cosmology, design, ecology, evolutionary biology, economics, futures and strategic planning, linguistics, management science, network theory, philosophy, quantum mechanics, sociology, and system science.

The course explores the many insightful connections between these niche domains, for example: how cosmology impacts our belief systems; how evolutionary biology reveals the dynamics of predator–prey landscapes; and how we can learn from these areas to better manage societies and promote equality.

“We learnt that to solve the hardest questions, we must begin with basic or simple questions”.

“At first it was frustrating because we just couldn’t connect all the dots,” said Rahbeeni, particularly the interplay between rational and intuitive thinking.

Quoting Albert Einstein, Rahbeeni said, “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift, and the rational mind is a faithful servant. But we have created a society that honours the servant and has forgotten the gift.

“And the course we have just completed has brought perspective to this quotation. It’s clear, as Einstein said, we are not going to solve tomorrow’s problems with today’s thinking”.

“We also learnt that to solve the hardest questions, we must begin with basic or simple questions.”

Uncertainty and complexity

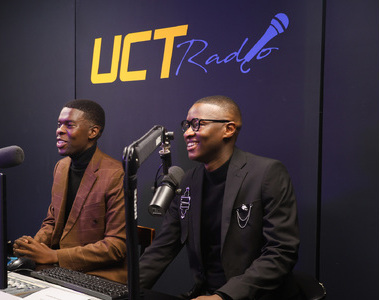

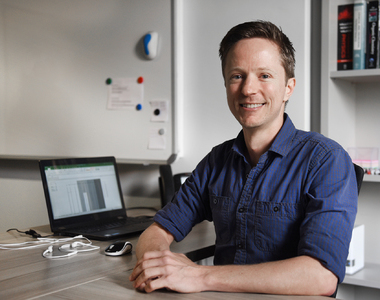

Among the graduates was chief creative officer of Digitexch, Faheem Seedat, a systems designer who works across a range of expertise in business development.

He explained, “The work I do involves a fair amount of creativity and problem solving which I really enjoy. Designing human-centred experiences, both digital and physical, is the chief aim of my work and the teams I work in”.

The course had been transformational, Seedat said.

“It transforms the thinking process and the fundamental neurological makeup of the psyche. Complexity science has encouraged me to embrace uncertainty and complexity rather than seeking simplistic answers for complex phenomena.”

He had also learnt to see problems and challenges as dynamic and evolving, requiring adaptable and holistic solutions over time, considering multiple perspectives, and recognising the ripple effects that actions can have on interconnected systems.

“The only certainty we can offer is that which involves nature’s way: always evolving”.

“Complexity science has fostered a sense of curiosity and a desire to explore the underlying mechanisms driving complex systems,” he said. Interdisciplinary thinking had also opened his eyes to potential solutions from unexpected areas, and the ability to think through things with a better understanding.

To those keen to tackle the course, Seedat’s advice is that students schedule time to complete it and immerse themselves “with intent” in understanding complexity science.

“The course introduces the field in a comfortable way but does not follow the traditional teacher–learner model. Rather, it uses a model of self-directed learning guided through collaboration.

“As the course offers a clause that because all knowledge is not known, one can never solve all problems for all of time. The only certainty we can offer is that which involves nature’s way: always evolving”.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.