Questions on bio-bricks grown from urine answered

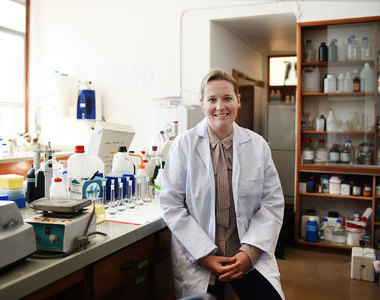

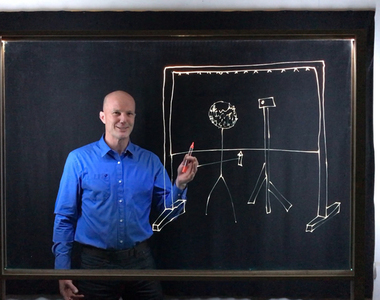

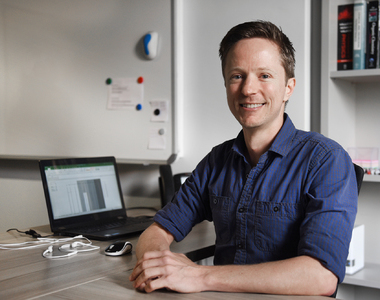

16 January 2019 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Robyn Walker. Read time 4 min.

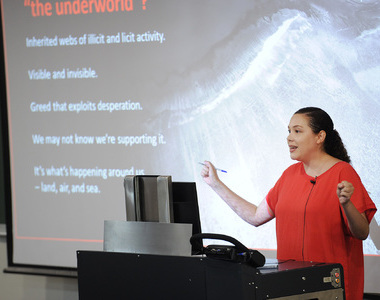

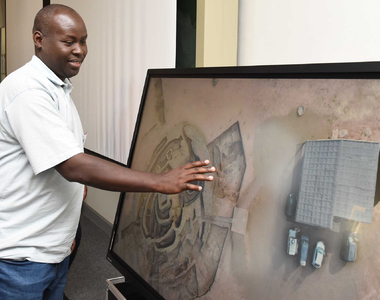

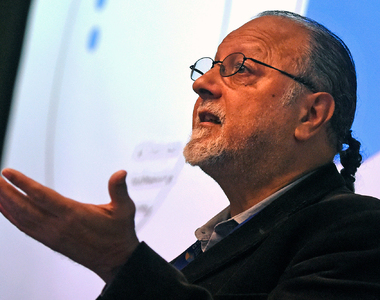

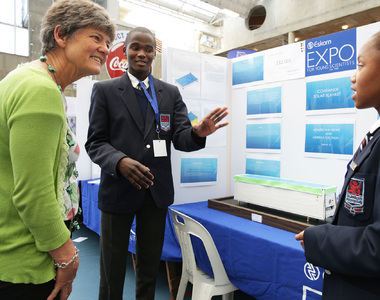

The recent story on the first bio-brick grown from human urine made headlines around the world. It was picked up by 142 news outlets in 23 countries, with a potential media reach of 248 million people in the first five days after the announcement was made. Project leader Dr Dyllon Randall’s subsequent public lecture late last year answered common questions about the project.

Randall, together with his master’s student Suzanne Lambert and honours student Vukheta Mukhari, have been swamped by media queries since the story broke on 24 October, 2018.

The lecture, attended by students and staff, international visitors and representatives from NGOs, government and industry, was held under the banner of UCT’s Future Water Institute. Randall is both a core member of the institute and a senior lecturer in water quality in the Department of Civil Engineering.

Here are Randall’s answers to common questions about the bio-bricks:

So what’s the big deal about bio-bricks?

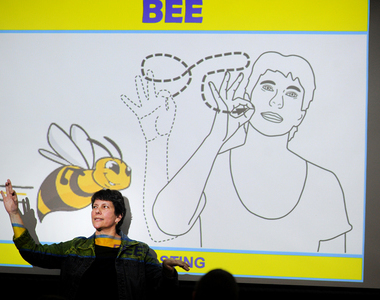

“With sustainability in mind, we need a paradigm shift. We should be rethinking waste [like urine], focusing on resource recovery. We need sustainable processes that reduce carbon emissions. We need to recycle nutrients and other material. Resource recovery is important for a sustainable future. Projects like these help to create paradigm shifts through education.”

How does this process reflect a circular economy?

“We need alternatives for kiln-baked bricks. Modern sanitation is inefficient at processing waste, especially when three key ingredients for inorganic fertiliser – nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous – can be retrieved from urine. Once is not enough. Our current economy is linear: we take, we make, we dispose. The circular economy focuses on making, using and recycling.”

“The language we use when we refer to waste is important. We say wastewater. Why not call it a resource instead?”

Why is urine called liquid gold?

“The language we use when we refer to waste is important. We say wastewater. Why not call it a resource? Why say sewage treatment plant? Why not call it a nutrient recovery plant? We say urine is a waste [product]. Why not say urine is liquid gold? Changing our language helps create paradigm shifts. In addition, we need to address multiple sustainability goals. For example, this project addresses clean water and sanitation; industry, innovation and infrastructure; sustainable cities and communities as well as responsible consumption and production. And indirectly, probably multiple others.

Do the bricks smell?

“Yes, they do, because the by-product is ammonia, but only for a short while. The bio-bricks lose their ammonia smell after drying at room temperature for a day or two, and are safe to use and handle.”

Would this process work at scale?

“I think it would. There’s a company called BioMason that grows 2 500 bricks a day using synthetic urea, which is commercially viable at scale.”

Can animal urine be used?

“If it’s fresh – not older than 48 hours – or you would have lost most of the urea.”

If you remove urine from the sewage works, are you just creating another problem?

“No. Research has shown that diverting urine out of that waste stream means that the nutrient load is substantially reduced and, as a result, wastewater treatment plants generally will become net energy producers.”

Is there a medium other than sand that can be used to grow bio-bricks?

“Yes. The only reason we used sand – which I don’t think is sustainable – was to see if the process would work. So, ultimately, we should be using waste products for the medium such as fly ash or sludge; anything we can glue together would work, in theory.”

How long does it take to make the brick?

“It depends on how strong you want it to be. The maximum length of time we’ve left it [in the mould] has been eight days. To optimise the process, you’d want to reduce that time. That will require further research.”

Does the health status of the urine matter?

“We haven’t really gone into that, but the other beauty of this process is that adding calcium hydroxide to the urine and operating at a really high pH kills harmful pathogens and bacteria. But we have to test that further.”

Common journalistic mistakes

In sharing the news of Randall’s work, some journalists have made several errors in their reporting.

Randall elaborates: “Firstly, we produced a bio-brick from urine, not a conventional brick. Other practitioners have previously made mud bricks using human urine. We use bacteria and a process called Microbial Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation (MICP) to create our bio-bricks.

“Secondly, BioMason uses synthetic urea for their process, not synthetic urine. Finally, this is not the world’s strongest ‘brick’ – it still requires further testing to improve the strength.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.