GBV: How will it end?

25 August 2020 | Story Nadia Krige. Photo Lerato Maduna. Read time 8 min.

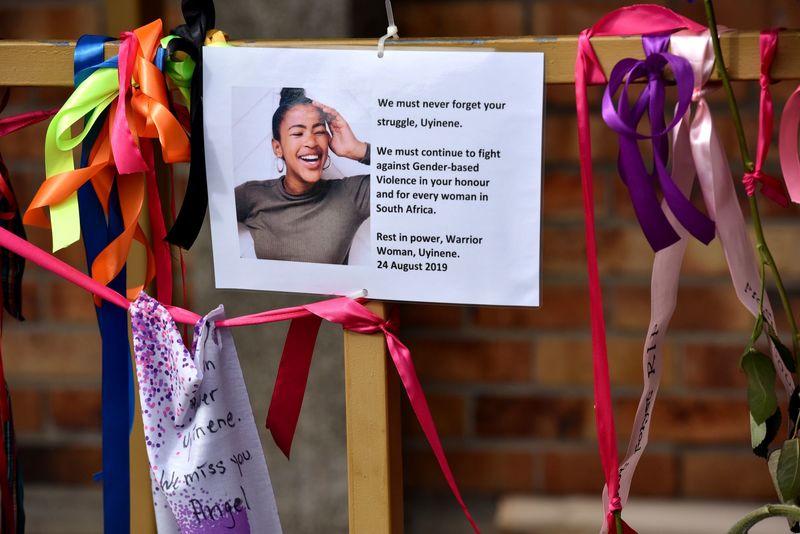

On 24 August 2019 University of Cape Town (UCT) first-year student Uyinene Mrwetyana went to the post office to pick up a parcel and ended up being brutally raped and murdered by a male post office worker. To commemorate the anniversary of this tragic event, the Uyinene Mrwetyana Foundation (UMF) initiated a webinar to discuss the pervasive nature of men’s violence against women in South Africa.

A poignant example of just how widespread the scourge of men’s violence against women is in South Africa is the fact that one week into Level 5 of the nationwide lockdown more than 2 000 cases of gender-based violence (GBV) were reported on the South African Police Service’s GBV hotline.

“This is estimated to be at least three times the rate prior to lockdown,” said Thandi Matthews of the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC), who participated in the webinar as a respondent to the panel discussion.

Hosted in partnership with the Psychological Society of South Africa and the University of South Africa (UNISA)-South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) Masculinity and Health Research Unit , the webinar was organised at the prompting of Nomangwane Mrwetyana, Uyinene’s mother and the director of the UMF. It delved into the reasons why men’s violence against women in South Africa is not changing swiftly enough and what can be done to remedy this.

The webinar was chaired by Professor Kopano Ratele, the director of the UNISA-SAMRC Masculinity and Health Research Unit, and took the form of a discussion among a panel of scholars, thinkers and activists at the forefront of gender issues in South Africa.

Panellists included UCT’s Professor Floretta Boonzaier from the Department of Psychology, Associate Professor Malose Langa and Associate Professor Peace Kiguwa from the Department of Psychology at the University of the Witwatersrand and Reverend Bafana Khumalo, the director of strategic partnerships at Sonke Gender Justice.

A question of language

Professor Boonzaier started the discussion with a critical look at the language we use when talking about and reporting on GBV.

“Language, we know, is very important for bringing things into public consciousness and for mobilisation,” she said. “In the current moment, I would argue that GBV is a term that is emptied of meaning. We talk about GBV without talking about misogyny – the hatred directed at women – which is a very important element of this violence.”

“When we speak out against GBV … Are we speaking out against violence against trans women? Against black lesbian women? Against black migrant women and sex workers, for example?”

Apart from this, she also highlighted the fact that we need to pay close attention to who the victims are that we talk about when talking about men’s violence against women and who gets left out of the narrative.

“When we speak out against GBV … Are we speaking out against violence against trans women? Against black lesbian women? Against black migrant women and sex workers, for example?”

Calling for a different kind of GBV reporting

Turning her attention to the media’s role in reporting on men’s violence against women, Boonzaier asked why it is that we only see reports on specific forms of GBV like rape and intimate-partner violence when they result in the death of a woman. This, she said, has contributed to a media landscape where violence against women has become a spectacle stripped of its social and historical context that ends up having little to do with embedded systems of patriarchy, male entitlement and misogyny.

“We act surprised as though misogyny, trans- and homophobia and sexism aren’t part of our daily realities.”

“Every time a woman is brutally murdered in South Africa, we express outrage and surprise,” said Boonzaier. “We act surprised as though misogyny, trans- and homophobia and sexism aren’t part of our daily realities, as though we don’t currently have a war on women’s bodies.”

In her presentation, Boonzaier called on the media to change their approach to violence against women by steering clear of episodic and incident-based reporting that places a high premium on graphic and shocking details. She argued that there has to be a commitment to thematic reporting that includes detailed, contextualised, grounded stories on GBV.

“Steering clear of episodic reporting will also mean that the types of violence that are normally silenced, like intimate-partner violence or sexual harassment, will feature in narratives of violence.”

Acknowledgement and accountability

Addressing the issue of men’s violence against women by focusing only on women is a luxury South Africa can no longer afford. Instead, intensive efforts need to be made to dismantle the toxic influence of patriarchal masculinities on men.

“We need to debunk the boyhood code among young boys in crèches and primary schools – the code that [says] boys must be tough, must be strong, emotionless,” said Associate Professor Langa. He recently released Becoming Men: Black masculinities in a South African township, a book which follows the lives of 32 boys from Johannesburg’s Alexandra township over 12 seminal years in which they negotiate manhood and masculinity.

Using a striking metaphor, Langa described how this specific code of masculinity leads to young men who are emotionally crippled zombies, devoid of the ability to express their emotions in healthy ways.

“We need to help boys and men to deal with the pain of the cost of manhood.”

“We need to help boys and men to deal with the pain of the cost of manhood. We need to help boys and men process any hurt arising out of their home or home spaces, as we all know that some home spaces are characterised by so much abuse and neglect and the sense of abandonment with regards to their fathers.”

Taking this point one step further, Associate Professor Kiguwa said that while it is important to acknowledge the particular pain patriarchy has inflicted on men, it cannot come at the cost of the responsibility men need to take in terms of their actions.

“Dismantling patriarchal culture is the work [we need to do],” she said. “Patriarchy hurts men and women. But men hurt women. So, how do we engage these two realities?”

A shared responsibility

While there is no simple answer to this question, the panellists agreed that ending the scourge of men’s violence against women and children, but also other men, is the responsibility of society as a whole.

Kiguwa argued that this requires acknowledging that violence has multiple causes that intersect but also often contradict one another and that, therefore, the responsibility for dealing with violence against women extends far beyond a fair and efficient criminal justice system.

“When we start thinking of violence in terms of a polycausal problem, [it becomes clear] that every sector of society needs to [take responsibility].”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.