History mustn’t repeat itself for COVID-19

10 March 2020 | Story Howard Phillips. Photo Wikimedia Commons. Read time 6 min.

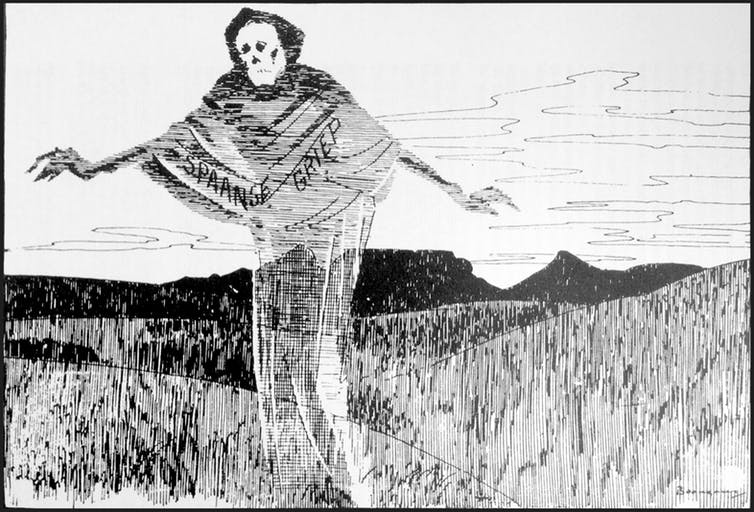

As the issue of repatriation of foreign nationals from China grabs the headlines in South Africa and elsewhere on the continent in the wake of the spread of COVID-19, there are some important lessons that can still be drawn from events 102 years ago in 1918 when an earlier epidemic, of so-called Spanish flu, arrived in the country.

This was the most devastating pandemic of modern times, killing more than 50 million people around the world (or 3%-4% of the globe’s population) in just over a year.

South Africa was one of the five worst-hit parts of the world. About 300,000 South Africans died within six weeks. That represented 6% of the entire population. After it had finally ebbed, a doctor reflected in the South African Medical Record in January 1919:

It has truly been an irreparable calamity which has fallen on South Africa.

Certainly the world is a very different place in 2020, not least in the speed of international travel compared to that in the steamship-era of 1918. Yet, the ways in which viruses behave and humans respond have not changed so much. That’s why there are still important lessons to be learnt from the catastrophe of 1918. This is particularly true when it comes to quarantining people infected with the virus, and their contacts.

The Spanish flu episode highlights some elementary mistakes made back then which must be avoided at all costs today to prevent another public health disaster.

Elementary mistakes

Towards the end of World War I, in September 1918, two troopships arrived in Cape Town from England carrying over 2,000 black South African Labour Corps soldiers. They were being repatriated after spending over a year behind the lines on the battlefields of France and Belgium where, as non-combatants (the South African government of the day did not allow black people to bear arms), they had provided ancillary support for the white soldiers in the frontline.

Their voyage included a coaling stopover in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where Spanish flu was already raging. Within days of their departure from there, cases of influenza began to appear aboard both ships. When the first of them docked in Table Bay, 13 of the soldiers were still laid up.

The corps’ medical officer insisted that the influenza on board was similar to ordinary influenza. Nevertheless, as a precautionary measure, the state’s local medical officer had the sick troops placed in isolation at 7 Military Hospital in Woodstock. The rest of the men were put under quarantine at a military camp at Rosebank. There they where all medically examined thrice in 72 hours for signs of influenza before they could be demobilised.

But these examinations were rather cursory. And three days later all were allowed to board trains for their homes across the country. It is clear that the enforcement of the quarantine at the camp was cursory too. A local journalist wrote in the Cape Argus, the Cape Town newspaper, on 9 October 1918 about how some of the impatient soldiers were seen on the

prowl in shoals about the Peninsula, notably in District Six.

Within a day of the soldiers having left the camp on trains for home, influenza cases began to appear in a host of sites. These ranged from the staff at the camp and 7 Military Hospital and members of the transport unit which had ferried the returned soldiers from the harbour to fishermen and stevedores working in the docks.

But by then the trains were well on their way, carrying the newly-discharged soldiers all over South Africa. Even before they disembarked, some had begun to show symptoms of influenza. From as remote a district as Tsolo in the deep rural Transkei, the local magistrate was soon reporting that, since the arrival of a batch of soldiers

sickness has become rife … in village and country and people are being brought in to local doctor by wagon and sledge loads. (Phillips, ‘Plague, Pox and Pandemics’, p. 79)

Spanish flu had arrived, becoming more lethal by the day.

Inexorably infecting the entire country, railway station by railway station, it engulfed the whole of South Africa within weeks, during what contemporaries called ‘Black October’. It had been allowed to run everywhere at once, like spilt quicksilver fulminated one magazine.

Lessons

One hundred and two years later South Africa’s departments of defence and health should heed the lesson of 1918 about the need to ensure that precautionary measures are rigorously implemented to the letter. If not, by the end of this year the Cape Times may be echoing what it wrote in the midst of ‘Black October’ on 15 October 1918, that the Department of Public Health had

lamentably failed in rising promptly and effectively to the emergency … Instead of showing itself the provident and well-prepared authority that we have a right to expect … it showed a lack of imagination and initiative that were wholly deplorable.

Howard Phillips, Emeritus Professor of History, University of Cape Town.

UCT’s response to COVID-19

COVID-19 is a global pandemic that caused President Cyril Ramaphosa to declare a national disaster in South Africa on 15 March 2020 and to implement a national lockdown from 26 March 2020. UCT is taking the threat of infection in our university community extremely seriously, and this page will be updated with the latest COVID-19 information. Please note that the information on this page is subject to change depending on current lockdown regulations.

Minister of Health, Dr Joe Phaahla, has in June 2022 repealed some of South Africa’s remaining COVID-19 regulations: namely, sections 16A, 16B and 16C of the Regulations Relating to the Surveillance and the Control of Notifiable Medical Conditions under the National Health Act. We are now no longer required to wear masks or limit gatherings. Venue restrictions and checks for travellers coming into South Africa have now also been removed.

Read the latest document available on the UCT policies web page.

Campus communications

2022

UCT Community of Hope Vaccination Centre

On Wednesday, 20 July, staff from the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Faculty of Health Sciences came together with representatives from the Western Cape Government at the UCT Community of Hope Vaccination Centre at Forest Hill Residence to acknowledge the centre’s significance in the fight against COVID-19 and to thank its staff for their contributions. The centre opened on 1 September 2021 with the aim of providing quality vaccination services to UCT staff, students and the nearby communities, as well as to create an opportunity for medical students from the Faculty of Health Sciences to gain practical public health skills. The vaccination centre ceased operations on Friday, 29 July 2022.

With the closure of the UCT Community of Hope Vaccination Centre, if you still require access to a COVID-19 vaccination site please visit the CovidComms SA website to find an alternative.

“After almost a year of operation, the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Community of Hope Vaccination Centre, located at the Forest Hill residence complex in Mowbray, will close on Friday, 29 July 2022. I am extremely grateful and proud of all staff, students and everyone involved in this important project.”

– Vice-Chancellor Prof Mamokgethi PhakengWith the closure of the UCT Community of Hope Vaccination Centre, if you still require access to a COVID-19 vaccination site please visit the CovidComms SA website to find an alternative.

Frequently asked questions

Global Citizen Asks: Are COVID-19 Vaccines Safe & Effective?

UCT’s Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine (IDM) collaborated with Global Citizen, speaking to trusted experts to dispel vaccine misinformation.

If you have further questions about the COVID-19 vaccine check out the FAQ produced by the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation (DTHF). The DTHF has developed a dedicated chat function where you can ask your vaccine-related questions on the bottom right hand corner of the website.

IDM YouTube channel | IDM website

“As a contact university, we look forward to readjusting our undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in 2023 as the COVID-19 regulations have been repealed.”

– Prof Harsha Kathard, Acting Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Teaching and Learning

We are continuing to monitor the situation and we will be updating the UCT community regularly – as and when there are further updates. If you are concerned or need more information, students can contact the Student Wellness Service on 021 650 5620 or 021 650 1271 (after hours), while staff can contact 021 650 5685.