Water: the most precious resource of all

17 September 2018 | Story Kim Cloete. Photos Je’nine May. Read time 9 min.

The roles of both individuals and industry in conserving the most precious of all resources – water – were at the centre of a symposium hosted by the Future Water Institute at the University of Cape Town (UCT) on 14 September.

Researchers, students, local government, industry and civil society interacted during the “Regenerative water futures: tensions in resource scarcity” symposium programme.

They heard about the lessons that had been learnt from Cape Town’s water crisis, which at its height generated bristling tension, and the mining industry, which has at times been in conflict with the community about the way in which water is managed.

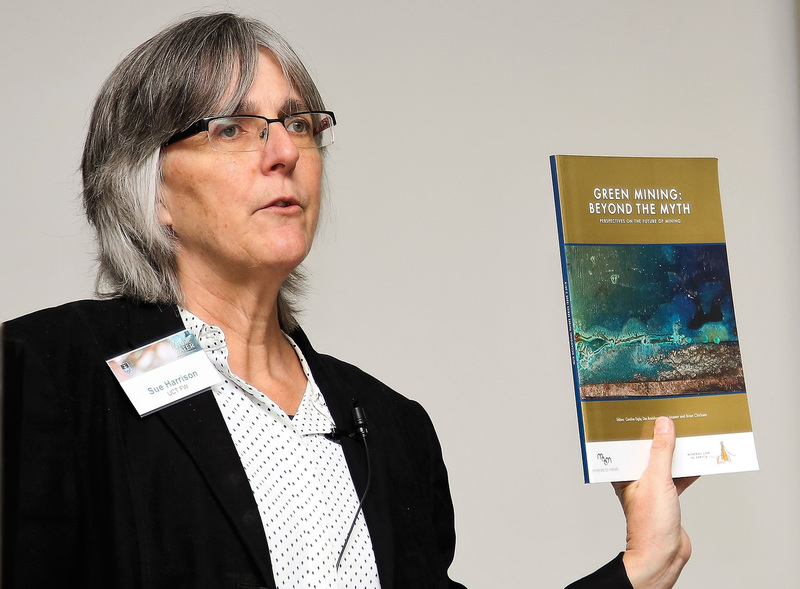

Director of Future Water, Professor Sue Harrison, said the symposium aimed mainly to integrate technical, management-based and people-focused aspects of water supply, demand and use patterns, looking at water through both the urban-centred lens and the lens of mining regions.

The input from speakers, round tables and forums will be compiled into a Regenerative Water Futures publication to be launched just before the Mining Indaba in Cape Town next February.

Nozipho January-Bardill, who is a non-executive director on the board of AngloGold Ashanti, said that, historically, water-consuming industries such as mining and agriculture had tended to take water for granted. Companies had relegated environmental concerns to the sidelines and strictly within the space of Corporate Social Investment (CSI).

Thankfully, this is slowly changing, she said

Turning point

The inclusion of business in the process that led to the adoption of the United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals was an important turning point. At a board level, January-Bardill added, a shift is also under way.

“Many of us on social and ethics committees are grappling to make a difference in moving safety, health and environmental, community and governance issues from the margins to the centre of our business activities.

“This too holds for the inter-relationship between the mining sector and its approach to managing water.”

Irresponsible water usage in the way minerals are extracted has had ripple effects on communities and the environment for decades, she added.

“Many of us on social and ethics committees are grappling to make a difference in moving safety, health and environmental, community and governance issues from the margins to the centre of our business activities.”

According to January-Bardill, executives are now realising that they need to be more accountable in the reporting of environmental and natural capital dependencies and impacts. They also have to come up with viable solutions to environmental risks.

“Boards want to avoid local community tensions and national political fallouts with governments, as such tensions threaten our legal and social licence to operate,” she said.

In turn, donors are also increasingly aware that disputes and grievances over natural resources and the way they are managed can exacerbate social tensions.

Globally, the mining sector has experienced the reluctance of a raft of environmental protection agencies in many jurisdictions to issue or renew permits for production.

“Many of them are exercising stricter oversight over water usage and management to address the impact of pollution on their citizens and communities who live around the mining operations,” said January-Bardill.

She added that proper management of natural resources has the potential to contribute to the common good and result in profoundly positive impacts.

“Whether we move on a path of degradation and destruction or on a higher road of a shared and sustainable future for coming generations, it is important that we start with a people, planet and peaceful-centred ideology of managing natural resources to inform the choices we make.”

Waterborne infections

Mjikisile Vulindlu, from the City of Cape Town’s Scientific Services department, said the recent drought that gripped the city had been a huge learning curve.

He said Cape Town has always been proud of its reputation for high-quality drinking water. But during the drought, this was put under pressure. An increase in waterborne disease is known to become a problem during times of water scarcity, and the city had to guard against this.

Vulindlu said complaints about water discolouration, odour and taste increased between July 2017 and June this year.

Concerned about the possibility of waterborne bacterial infections, the city strengthened its oversight in various ways, he said.

It increased water quality data management, trained samplers and operators, increased chlorine and turbidity monitoring, and ensured that source water, reservoirs and new alternative water resources were protected. Final treated water was tested and showed a low risk for E.coli.

“Worldwide we are looking at mass extinction of non-human species.”

Water infrastructure

Cultural anthropologist Professor Veronica Strang, from Durham University in the United Kingdom, stressed the important of including all players in the water space.

Looking back at history, she said, one of the most radical shifts in engineering had been the development of steel and concrete. This had enabled people to build the 57 000 dams around the world up until now.

The “magical material” of concrete “can fulfill almost any engineering vision we have in theory”. But, she pointed out, while concrete may stand for durability, and iron and steel for strength, they don’t last forever.

“Water is the enemy of dams in that it seeps into cracks, it expands, it creates rust, and sometimes it arrives in amounts that are too great to withstand,” Strang warned.

She said the imposition of water infrastructure and patterns of consumption had also come with rising costs to non-human species and the environment.

“Worldwide, we are looking at mass extinction of non-human species. We need to consider a crucial difference between infrastructure focused on short-term, human-centred objectives and immediate levels of growth and providing water and sanitation for all, and what aims for longer-term sustainability.”

Strang said bringing people together to solve problems in the water space was key. She described her work with 17 different disciplines, from geologists, biologists and anthropologists to engineers and artists, in a recent river catchment project.

Africa-centred solutions

She also commended Future Water for involving a range of different disciplines in its work on water, as she believed this was the path towards a more sustainable future.

Strang also contributed to a lively panel discussion on water management guidelines with climate scientist Chris Jack from UCT, Ntatho Minyuku from the SA Planning Institute, and Tony da Cruz from AngloGold Ashanti.

Issues of delivery, infrastructure, communication and conflict around water were on the agenda for this panel, chaired by Mpho Ndaba from the national Department of Monitoring and Evaluation.

Round-table discussions were held on topics such as liveable neighbourhoods, post mine succession, ecological infrastructure, new “taps” or water resources, and water in relationships of care.

In closing the event, Harrison noted as key points the “centrality of water, the complexity surrounding securing water resources, the need for multi-stakeholder perspectives, the importance of resilience and the key role of champions and pioneers in achieving a water-secure future”.

Interdisciplinary research and solutions

UCT executive director of Research Marilet Sienaert said Future Water was one of four major interdisciplinary institutes that had been established at UCT and focused on achieving Africa-centred solutions to global problems.

Increasingly, universities need to show they are making a difference in society, she said.

“Research is a very costly exercise and we need to be able to justify and demonstrate what has been achieved.”

“University management, funders, research partners and city councils want to see the impact of what you are doing. Research is a very costly exercise and we need to be able to justify and demonstrate what has been achieved.”

Sienaert added that, through its symposium, Future Water had exemplified the aims of interdisciplinarity, by providing evidence and participation beyond academia, and leveraging partnerships across disciplines, constituencies and stakeholders.

Future Water projects have been a vibrant hub of activity over the past two years, with researchers working with the government, industry and other partners in projects in water catchments and other areas. Future Water researchers are drawn from all six faculties in the university.

Visit the Future Water Institute website.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.