Lingering high-pressure cells limit winter rains

29 June 2018 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Michael Hammond. Read time 6 min.

Although the Western Cape has enjoyed good rains over the past few weeks, climatologists have cautioned that high-pressure cells lingering over the western and southern Atlantic are pushing cold fronts further south, preventing these rain-bearing systems from penetrating deep inland. The result has been less winter rain – and a persisting drought.

Dr Peter Johnston, of the Climate System Analysis Group, says it’s hard to make predictions about cold front patterns over the Western Cape. While dam levels have increased to 42.7% of storage capacity, the winter prognosis is uncertain.

Speaking on CapeTalk this week, Johnston said that over the past few years the high-pressure system to the west of the country has been nudging the rain-bearing cold fronts further south, away from the country.

“This means that while we are receiving some rain, in a normal winter there should be a whole lot more from where that came from. We’re not getting those full frontal systems as in the past.”

Loitering high-pressure cells

High-pressure cells are a normal feature of our weather system, he explains. Rising air from the equator descends around 30° north and south of the equator.

“That descending dry air is essentially a high pressure, system, and it gathers together in cells so it’s not a continuous band,” Johnston said. “As the seasons change, these cells move further to the north and south, so in summer the cells are right over us and there’s little chance of cold fronts affecting the south-western Cape. This is because they are also further south.”

During winter the high-pressure cells shift northwards, and Cape Town is then more directly in the path of the incoming cold fronts. But these pressure cells have been shifting around, says Johnston.

“We don’t know if it’s long term, but over the past three years we’ve found that these high-pressure cells seem to have intensified; they’re stronger, and positioned further south.”

But this winter (so far), the high-pressure cells have been behaving normally. A strong cold front hit the province on Monday, bringing heavy rains to the region, although it didn’t penetrate very far inland. There are more fronts predicted this week, and significant rainfall for Sunday.

“We are concerned that these cold fronts have not been hitting the Western Cape as full on as before, or penetrating as deeply into the interior Western Cape and Northern Cape.”

“We are concerned that these cold fronts have not been … penetrating as deeply into the interior Western Cape and Northern Cape.”

Climate change or blip?

One theory is that climate change is the cause of these intensified high-pressure cells.

“But it’s very difficult to prove, because you need many monitoring stations – especially over the ocean, and you must consider that the synoptic charts we see are drawn quite liberally from readings and atmospheric recordings.”

Climate systems PhD student Stefaan Conradie added: “The issue is also the period of data availability for the Southern Hemisphere; before the days of satellites, data are really poor, and the big droughts of the past were in the 1930s and the 1970s, so we can’t really compare this drought in terms of the mechanisms of previous ones.

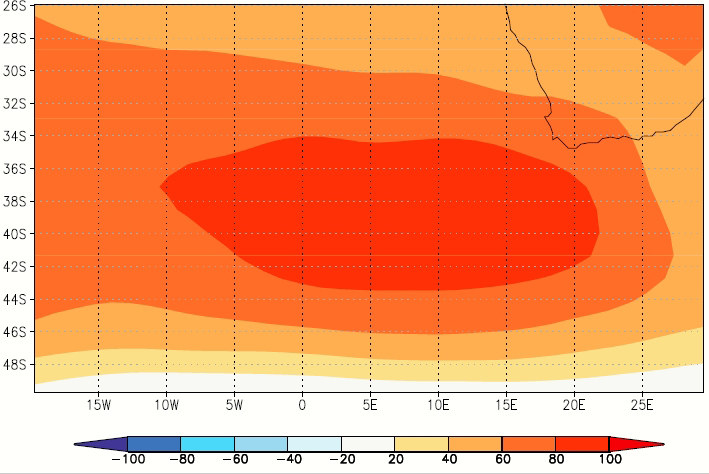

“We don’t know whether this high-pressure shifting is new, or whether this is always the cause of big droughts in Cape Town. The data suggest that our core winters (June, July) haven't been that far from normal in terms of the highs, but the April, May, August, September and October patterns have been very different (see diagram below).”

Weather watching

“Let’s just say that if these high-pressure cells do block the cold fronts again this year, it’s likely that we’re not going to get above normal rainfall – and we really don’t need this right now, so we’re watching them very carefully,” Johnston added.

Looking at the synoptic chart, he says the front due to hit the region on Sunday, 1 July, is likely to bring some heavy rains.

“Having said that, if we need, say, another 300 mm between now and the end of September, we need 15 rain episodes of 20 mm – and that is a substantial amount of rain. That means 15 days of 20 mm. And we haven’t had 15 such individual days this year thus far. So, we’re hoping that we can get more rain days over the next month or two.

“But as we’ve noticed, we just don’t seem to be getting those heavy rainfalls very often.”

(Please note that although dam levels have been rising, water restrictions will remain until dams reach 80% of capacity.)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.