How to honour Archie Mafeje's legacy

01 April 2015 | Story by Newsroom

Forty–seven years ago, UCT social anthropology alumnus Dr Archie Mafeje successfully applied for a senior lectureship at his alma mater, only for Council to withdraw his appointment a month later, drawing stinging criticism from staff and students.

Mafeje fled into exile and became an internationally recognised scholar in his field, earning the title of full professor, a title he held at UNISA until his passing at 71 in 2007.

Thoko Didiza – who was chairing the Archie Mafeje Annual Memorial Lecture, held on what would have been Mafeje's 79th birthday on 30 March at UCT – said the issues raised in this commemoration of the 'Mafeje Affair' were no different to those raised by the #RhodesMustFall campaign.

Similarly, Deputy Vice–Chancellor Prof Crain Soudien said that #RhodesMustFall sparked introspection of the very nature of the South African university. It was a major provocation that asked for deep thinking about the university's role and place in a South Africa wracked with "incredible division".

We might look to Mafeje's life and work for a response to that challenge, Soudien said: "We need to take Archie and his life and consider the kinds of ways in which he as an anthropologist began to think about these real questions, about what it means to be a human being. Archie did that in incredible ways."

It was a legacy with which UCT had struggled, Soudien admitted.

Honouring his memory

During his time at UNISA, Mafeje inspired scholars to pursue independent knowledge production, including indigenous knowledge systems, said UNISA's Prof Lesiba Teffo. So UNISA saw fit to set up a research institute, the Archie Mafeje Institute for Applied Social Policy Research, to carry Mafeje's research legacy forward, he said.

Mafeje's nephew, Sandile Swana, said that to oppress a people for any length of time "you must make it a priority to stunt their academic training and intellectual development". So Swana commended and challenged universities to "be a little bit more deliberate" in their recruitment, teaching, research and nurturing of "independent African students and thinkers".

Advancing the production of African scholars and intellectuals would be the "most excellent way of remembering Professor Archie Mafeje", said Swana.

Why wasn't Mafeje appointed?

Though his brief was to reflect on Mafeje as a peer, Prof Lungisile Ntsebeza politely corrected the programme by confirming that Mafeje was, in fact, his elder. Ntsebeza also pointed out that when Mafeje expressed a desire to teach at UCT after the exiles' return in 1990, he was made to reapply for a post, and was not even granted an interview.

"As a scholar, one of the reasons Mafeje wasn't appointed in the 90s was his stance, so to speak, on what he called colonial anthropology," said Ntsebeza. "His stance with respect to anthropology was of such a nature that, had he been appointed at UCT, he would have made this university an interesting place to live in.

"He would have caused interesting debates precisely because he would have been in fierce conversation with some of the chief anthropologists at UCT. But that opportunity was denied to us here at UCT."

Engaging with Mafeje's texts on land could be useful for students, staff members and the country as whole, suggested Ntsebeza. Mafeje was highly critical of the land reform model that South Africa adopted, which was based on large–scale commercial farming, large concentrations of land and production for the market.

Mafeje's views resonated with Colin Bundy's, who observed that in the late 19th century peasants competed successfully with white farmers to the extent that sharecroppers often produced so much that they were able to give more than half of that to white landowners.

"So Archie uses that scholarship to argue the case for small–scale farmers and dispel this notion that blacks cannot farm," said Ntsebeza.

To get Mafeje to stand up in his grave...

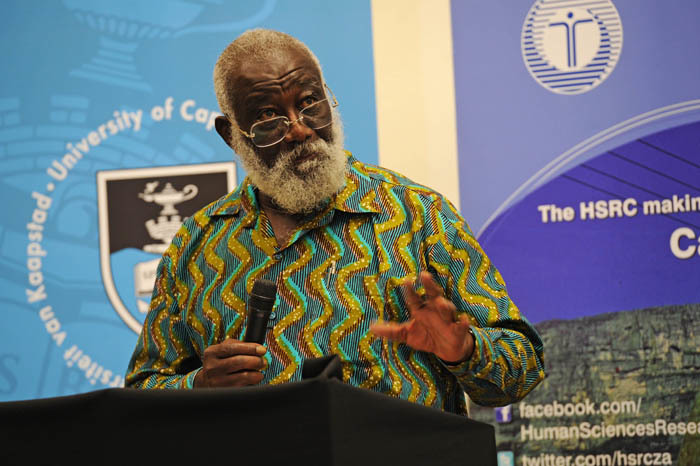

Professor Kwesi Kwaa Prah, renowned pan–African social scientist and the occasion's keynote speaker, described Mafeje as having a "fundamental preoccupation with the human condition in Africa".

The two had known each other for some forty years. Mafeje was a cosmopolitan, and this was matched by a "fervent Africanism", said Prah. Staunchly critical of "doublespeak", Mafeje's original political home had been in the Unity Movement.

Prah urged scholars to look at issues like curriculum ("who do you read?") and the "elephant in the room": language. Language lay "at the heart of all our problems", he said.

Take the story of Afrikaans, for example. Introduced to primary schools in 1913, Afrikaans was first taken to university in 1918.

"[In] 1925 it became official in Parliament; 1931, they translated the first Bible into their language; by 1940, 45, they could study anything, including 'space rocketry', in the language."

So why shouldn't it be possible that within about forty years African languages could be used to study anything in the world? He laid down that challenge to young scholars.

"These are issues I discussed endlessly with Archie – over bottles of wine,– he said, with his audience chuckling.

Prah's parting shot drew sustained applause: "If you want Archie to stand up in his grave, then [it is] this sort of Africanism – practical solutions to our problems – that you must pursue, solutions that will help us lift Africa from where we are now to equality with all other people."

Story by Yusuf Omar. Image by Michael Hammond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.