Creative Works Award: What Remains – a tour de force

05 February 2021 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo John Gutierrez. Read time 10 min.

Four University of Cape Town (UCT) academics were awarded two UCT Creative Works Awards for 2020: Associate Professor Nadia Davids and Professor Jay Pather for their production What Remains, and Nkule Mabaso and Associate Professor Nomusa Makhubu for their exhibition The Stronger We Become.

The award recognises major art works, performances, productions, compositions and architectural designs produced by UCT staff.

In the first interview, UCT News spoke to the collaborators of What Remains, a multi-award-winning production written by Associate Professor Davids and directed by Professor Pather. Davids is based in the Department of English Literary Studies. Pather is the director of the Institute for Creative Arts and teaches at the Centre for Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies.

What Remains is their first collaboration.

“In the work, four central figures … ‘move between bones and books, archives and madness, paintings and protest’, as they strive to reconcile past and present.”

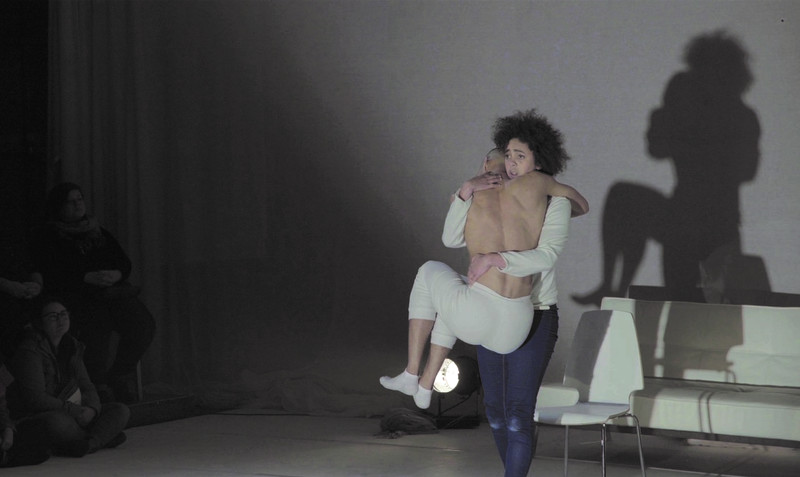

Years in the making, the production is a fusion of text, dance and movement and tells a story about the unexpected uncovering of a slave burial ground in Cape Town, the archaeological dig and the uncomfortable legacy of slavery. When the bones emerge, the city’s people – descendants of the enslaved, archaeologists, citizens and property developers – must deal with history, some hardly and some forgotten. Davids’ work draws on the uncovering of a slave graveyard at Prestwich Place in the city in 2003 during a site excavation. In the work, four central figures – The Archaeologist, The Healer, The Dancer and The Student – “move between bones and books, archives and madness, paintings and protest”, as they strive to reconcile past and present.

The citation notes that, “The published play, along with Davids’ accompanying essay and Pather’s notes on choreography, invites the reader not only to consider the text and its genesis, but to imagine the play’s staging, the ways in which bodies work to forge meaning in and through performance, and how Davids’ text suggests the choreographic.

“The work, concerned with the historical, with an active engagement with archive, social justice and the geographies of loss that characterise our city and our country, with disrupting received representations of oppressed peoples, and with responding to South Africa’s political life, is also undergirded by the understanding that art is not only informed by theory, but creates it, and that live performance is a particularly powerful space in which to stage these questions and invite responses.”

It continues, “The published play, along with Davids’ accompanying essay and Pather’s notes on choreography, invites the reader not only to consider the text and its genesis, but to imagine the play’s staging, the ways in which bodies work to forge meaning in and through performance.”

Helen Swingler (HS): What does this accolade mean to you and for your work?

Nadia Davids (ND): It’s wonderfully affirming. The award is for the different components and iterations of the project: the staging of the play, the publication of it and the research generated through and around it. In addition to it being an honour, I think it also signals UCT’s important commitment to, and understanding of, practice as research and the significance of creative work as a form of knowledge production within the academy.

Jay Pather (JP): I am also enamoured of receiving this as a collaboration. Recognition of this interdisciplinary approach to art making – the combination of text, theatre, history, politics and dance – is the affirming of interdisciplinary contemporary art that seeks to excavate our complex present.

HS: Is this your first UCT Creative Works Award?

ND: Yes.

JP: No, I also received the award in 2016 for my production Qaphela Caesar.

HS: The work described is very central to transformation in the way we view history and as a record of the country’s colonialist past and social activism. What has been the most fulfilling aspect of writing, designing, workshopping and staging this production?

ND: The vast majority of my creative and intellectual work was done in the researching and writing of What Remains. The design work, rehearsal process, the staging, the merging of text and choreography was all Jay Pather; the work of his imagination, daring and intellect. I had that rare privilege of getting to see my work take shape and form on the stage and for all sorts of new meanings and connections to become apparent.

“This rich, yet effortless melding of epochs in the writing inspired a mercurial approach to history as opposed to being weighed down by factual detail and a tortured past.”

JP: It’s hard to do anything without a vivid and dense text written exquisitely. Working with this text was one of the most fulfilling experiences as it bled so easily from a fierce present into a dark and haunting past. This rich, yet effortless melding of epochs in the writing inspired a mercurial approach to history as opposed to being weighed down by factual detail and a tortured past. Beyond that, I worked with a really strong cast of actors and dancers.

HS: As a collaboration involving text, dance and movement, what were the most challenging aspects of this project?

ND: I found it riveting. I’ve always understood that the body speaks, articulates, is a text in and of itself, but I hadn’t had the chance to see my own work transformed through movement before. Jay would speak a lot about how he approached the text itself as ‘choreographic’, as having movement and instruction embedded in it ... I hadn’t thought of the rhythms of writing in those terms before, so I was fascinated. Writing a play is fundamentally different to other forms of fiction because the final point is the performance. I always have very clear ideas about my characters but very hazy ideas about the actual staging. I was astonished by the breadth, depth, precision and sheer beauty of Jay’s vision and choices.

JP: For me it really was about how to maintain the sophistication of the text. Nadia’s text is disarmingly lucid. So, the challenge was how to maintain this lucidity, reduce the clutter of staging, while being faithful to and prompting the complexities of the dense metaphors and historic detail that the text presented.

HS: How does this project impact your teaching?

ND: My creative work is usually undergirded by a process of intensive reading and archival research, and I try to introduce this idea in the classroom as often as possible: that one need not demarcate between the two ways of thinking (creative and academic), that art contains its own methodologies and theory, that art requires the same rigour as critical inquiry, that approaching a creative work with an analytical eye can be a wonderfully interesting way of engaging a text. Some of my students, especially in their undergraduate years, become, understandably, very theory averse. The language of theory can be alienating and conceptually tough. I try to introduce the idea that there is much creativity in theory and much theory in creative works and speak to them about how the two can be woven together; that they don’t have to be artificially separated.

JP: Our students are constantly working with history and archive in their theatre making and choreography. Working with Nadia’s writing has helped inform a minimal and precise approach in bringing a weighty subject to dramatic text and performance.

HS: The work has a very evocative title – an interesting word play – but also leaves an intriguing question. Is this intended? What does remain for you in terms of this work and future collaborative ventures?

ND: Yes. The title … is intended as a statement but could also be a question. What remains of South Africa’s past? How does that past announce itself, over and over, in the present? We are in the very early stages of working on something new.

JP: The remains of our past and their presence in our contemporary lives is unmistakeable and unavoidable. Nadia’s title collapses time and space, and I think the play (both gently and urgently) asks us to see these as continuums. What we carry forward as a nation and as individuals depends on crucial decisions we need to make daily in processes of redress, redistribution and healing.

And on a more personal note, as Nadia hints at, what does remain is a strong desire to collaborate again.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.