A four-part drug to secure happiness

10 January 2014

Associate Professor of Classics Clive Chandler explains what Epicurean physics has to do with happiness.

"Who would have thought you could begin a conversation about happiness with mention of an ancient artefact?" starts Chandler.

He continues to describe how Diogenes, a wealthy man who lived in the city of Oenoanda around AD 120, in what is now southern Turkey, commissioned an inscription – thought to run to over 80 metres in length – on a large portico (or porch) that describes the philosophy of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Fragments of this inscription began to be discovered late in the 19th century, and made an important contribution to our understanding of Epicurean philosophy.

Epicurean philosophy is based on materialism, and the idea that pleasure is the greatest good. But pleasure in this instance is less about hedonism, as it is generally understood, and more about the idea that living a moderate and simple life gives the best chance of attaining a state of katastematic pleasure, which is made up of ataraxia (a state of mental tranquillity) and aponia (the absence of physical pain and discomfort), among others. Katastematic pleasure, in the eyes of an Epicurean, is the highest form of happiness.

Given the materialist conception of Epicurean physics – that the universe is comprised only of atoms (the smallest possible particles) and the void – it is no surprise that both the above states are seen as physical.

"Seeing the soul as a physical entity means that it is not surprising that the treatment of what we might call unhappiness is described by the Epicureans using the language of medicine. In other words, philosophy is seen as a kind of medical treatment for the soul."

So, what treatment does Epicurus recommend?

According to Chandler, the term tetrapharmakos, or four-part cure, is based on the name of a folk remedy poultice made up of four ingredients: pitch, pine, beeswax, and animal fat.

"As such, the tetrapharmakos can be seen as something simple, almost like a form of self-medication," he says.

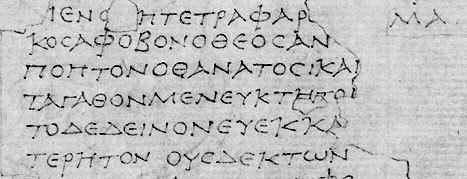

The Epicurean tetrapharmakos states the following:

Do not fear God,

Do not worry about death;

What is good is easy to get, and

What is terrible is easy to endure.

In Chandler's words: "The tetrapharmakos was something you used when you had already accepted the Epicurean philosophy; as such, I think it was something that was designed to be 'taken' in times of stress."

So what would an Epicurean have understood these apparently simple lines to mean? "We have the power to secure happiness for ourselves. Our intellect is responsible for all sorts of false opinions which cause us anxiety and discomfort, but if we use the intellect properly to scrutinise whether what we believe we want is natural and necessary, it can be the source of our mental health instead."

Strong medicine indeed.

Story by Ambre Nicolson. Photo of the tetrapharmakos by Guiseppe Casanova, via Wikimedia Commons.

This lecture was given as part of a symposium sponsored by UCT's Brain and Behaviour Initiative. Read more about what psychiatrist Dr Kerry Louw and philosophers Dr Tom Angier and Professor Thaddeus Metz had to say about happiness and well-being.

Read more:

Is happiness good for you?Happiness and virtue theory

Living well by ubuntu

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Books

Opinions

Focus

Previous Editions