Happiness and virtue theory

10 January 2014

UCT philosopher Dr Tom Angier explores what we mean when we talk about happiness and well-being, arguing that there is a necessary connection between living a morally good life and achieving a state of well-being.

What are happiness and well-being? In Angier's words: "In contemporary philosophy, there is a trichotomy of categories making up our ideas around these concepts: happiness (as a psychological state of mind comprised of things such as contentment), objective well-being (conditions necessary to flourish, such as shelter), and virtue or moral goodness.

"They're considered not to have much to do with one another," says Angier. "I argue that developing virtue is necessary to well-being, although not sufficient.

"I think a central obstacle to my argument is the accusation of moralism, a common accusation in contemporary literature, that argues that the idea that 'self-fulfilment' and living a virtuous life are distinct; or in other words that even if you're a really horrible person, you might be capable of being quite happy," says Angier.

"This implies some assumptions about what the moral is," argues Angier. He describes the case of Angela, a tired diplomat who postpones her retirement in the interests of doing her duty to the government she serves. In this case, Angier argues that from an Aristotelian moral viewpoint, Angela would not be obliged to continue working, since the Aristotelian conception of virtue is less demanding than, for example, a Kantian moral standpoint, which would argue that we are under a moral duty to act according to the categorical imperative (the idea in this case being that acting for the moral good is an unconditional and universal obligation). On the other hand, according to Angier, an Aristotelian might see Angela's actions as being good, but not necessary.

"Nonetheless, in Aristotle's view a flourishing genuine life is unattainable without suffering," says Angier. "In fact, the Aristotelian view covers how best to include suffering into our lives, because managing suffering is required in order to develop virtues such as courage, temperance and generosity, which are required to live a good life."

In other words, to have insufficiently developed virtues is to be unable to attain a state of well-being. For example: courage – the idea of facing danger for noble ends – may cause suffering; but it's necessary to attain its development as a virtue in order to live a flourishing life, and thereby attain a state of well-being.

"I also disagree with the modern conception, seen so often, that self-fulfilment and virtue are separate on the grounds of sentimentalism. According to positive psychologists, welfare must be protected from pain and suffering; but according to the Aristotelian view, protecting people from suffering actually means arresting their development of virtues, and thereby harming their ability to live a good and flourishing life."

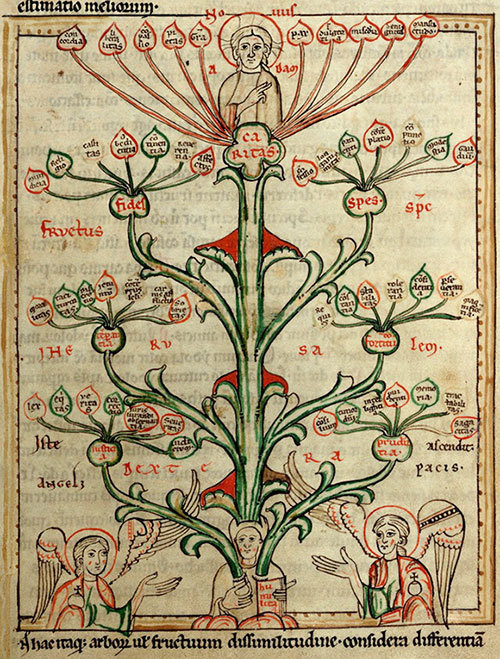

Story by Ambre Nicolson. Photo of Speculum Virginum, Tree of Virtues, Walters Art Museum c. 1200, via WikiMedia Commons.

This lecture was given as part of a symposium sponsored by UCT's Brain and Behaviour Initiative. Read more about what psychiatrist Dr Kerry Louw, philosopher Professor Thaddeus Metz and classic scholar Professor Clive Chandler had to say about happiness and well-being.

Read more:

Living well by ubuntuA four-part drug to secure happiness

Is happiness good for you?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Books

Opinions

Focus

Previous Editions