Inaugural address a journey into Islamic feminism

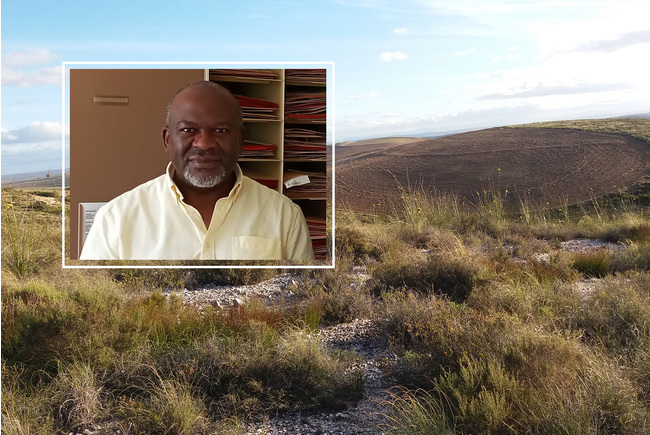

03 September 2024 | Story Lisa Templeton. Photo Lerato Maduna. Read time 9 min.Islamic feminism – is it the oxymoron of the naysayers or the proud product of long tradition? This was the topic presented by Professor Sa’diyya Shaikh, a professor of religious studies and the director of the Centre for Contemporary Islam at the University of Cape Town (UCT). Professor Shaikh is a global leader in her field and an inspiration to feminists, both within the world of Islam and beyond, who has dedicated two decades to the study of Islam, gender ethics and feminist theory.

“The term ‘Islamic feminism’ can provoke a range of responses that reflect the diverse perspectives and beliefs that people hold about both Islam and feminism, ranging from interest and curiosity to cynicism and outright rejection,” Shaikh said.

She was addressing a tightly packed gathering of distinguished guests who assembled in the Bremner Building’s Mafeje Room on 23 August to celebrate her inauguration into full professorship.

Having dubbed her lecture “Radical Critical Fidelity: Barzakhi Journeys in Islamic Feminism”, Shaikh unpacked her personal journey within her family, faith and research career – a journey that has balanced a deep love of Islam with the fidelity of the research approach and the imperative of social justice, unveiling thinkers, both historic and contemporary, who have influenced and inspired her.

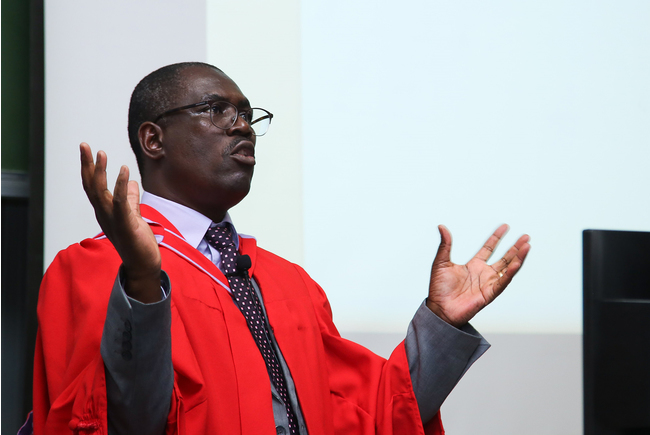

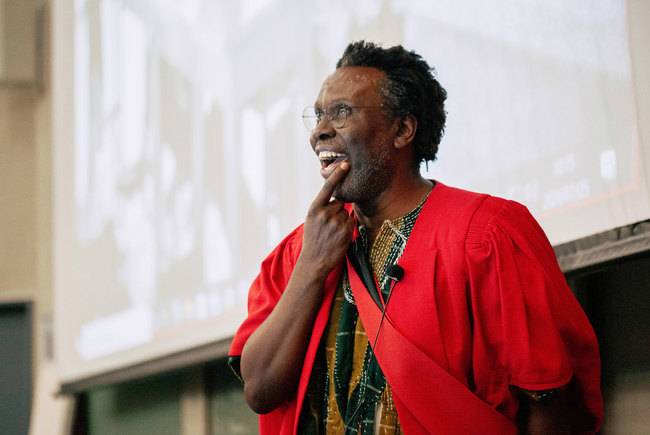

“An inaugural lecture is a special event on the calendar of a university, an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of an academic and to share their research,” said Professor Elelwani Ramugondo, the deputy vice-chancellor for Transformation, Student Affairs and Social Responsiveness, in her welcome address.

“Professorship marks the highest rank, one aspired to by academics. For a university such as ours, which is research intensive, we strive to balance the need for undergraduates to have an extraordinary experience with competing with the best in the world.”

Between sweet water and salt

In unpacking her topic, Shaikh, who was described by Professor Shose Kessi, the dean of the Faculty of Humanities, as a “phenomenon and a phenomenal feminist”, said reactions to Islamic feminism range from genuine interest, Islamophobic scorn, to the Muslim reaction of “What rubbish! Islam liberated women over 1 400 years ago, long before the West!”

Said Shaikh: “For them, the idea of Islamic feminism is not only unnecessary, but potentially dangerous, as it challenges their interpretation of Islam as a religion that has already provided all the necessary rights, roles and responsibilities of women.

“Finally, there are those Muslims who respond by saying ‘Alhamdulilah! Finally!’”

“Finally, there are those Muslims who respond by saying ‘Alhamdulilah! Finally!’ For these people, Islamic feminism is a movement that finally speaks to the intersections of their lives, and a harmonious blend of their commitment to their faith and their pursuit of justice.”

In examining her topic, Shaikh referenced the concept of the barzakh, an intermediate, liminal state which draws on the Quranic idea of an isthmus between two oceans – salt and sweet. It signifies a third space that holds both without becoming either, thus embracing multiplicity.

“The idea of embracing the barzakh invites us to occupy a third space, beyond the cruder binaries of theology versus religious studies, secular versus religious knowledge, subject versus object, male versus female, mind versus heart as separate modes of knowledge, scholar versus believer, activist versus academic.” In other words, resisting binaries opens the road to capacious forms of scholarly production.

Knowledge and activism are integrally connected

Shaikh defines Islamic feminism as both a knowledge and a world-making project, which provides a rigorous critique of sexism, through transformative intellectual and political work based on justice, freedom and equality, underscored by faith and an Islamic world view.

Raised on Islamic spirituality, where memories of a childhood spent in Durban include sharing an armchair with her dad while hearing stories of awliya, friends of God in Muslim history, and her mom leading women in evening prayer during Ramadan, while the men went to mosque. Shaikh said the love of God was closely intertwined with community.

Within her community were also ideas of men being in charge and teachings that God was to be feared, something contrary to what she had experienced at home.

Later, as a young adult, Shaikh would grapple with sexism, racism and ethno-centricism under an apartheid state, as well as prevailing social and religious norms which were discriminatory to women, birthing a commitment to activism and social justice.

Patriarchy infiltrates many traditions

Looking back on her decades of scholarship, Shaikh speaks of journeys and pathways, metaphors often used in Islamic tradition.

“It is crucial for us to recognise that the scholarly journey is shaped by our varying communities, intellectual traditions and political realities,” she said.

As a graduate student, Shaikh would begin to better understand that patriarchy infiltrates many traditions. She credits Professor Denise Ackermann and the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians as a community that helped her discover how women from diverse religions resist and engage with faith as the foundation for justice and human dignity.

“Secular feminists who dismiss all religion as indefensibly patriarchal, disregard the dimensions of religion that have in fact empowered, sustained and strengthened women through the most gruelling aspects of their lives, a point that emerged in my empirical studies on Muslim women in South Africa.”

A form of friendship within tradition

In tackling her work, Shaikh draws on an established tradition of feminist hermeneutics, an interpretive approach which uses a critical lens to comb for male-biases in tradition.

“Increasingly, it became clear that many of the sexist practices I observed within my context were based on a deeper structural problem: a gender-biased, discriminatory conception of human nature, or what might be described as a deficit in gendered religious anthropology.”

Her study of Islam within South Africa has drawn on the ways ordinary Muslim women have navigated patriarchal power in their families and communities (including a study on gender-based violence), Sufi feminist theology, and religious and spiritual leadership by women.

Professor Kessi said: “There is an intimacy about Professor Shaikh’s work that hones in on the profiles of women’s lives in Islam. She blurs the lines of the particular and the universal, so when she writes about women in Claremont, a stone’s throw away, her work has an impact on either side of the globe.”

Shaikh said: “It was within exploring Sufi theology that my friendship – or rather love affair – with a 13-century polymath and Sufi, Muḥyī al- Dīn Ibn ʿArabī, began”. Within Arabi’s writing, she found not only a spiritually ripe theology, but a profoundly egalitarian understanding of personhood and social relationships.

“For Islamic feminists, tradition and religious knowledge are approached as open, dynamic and ongoing processes.”

She also mentioned Professor Amina Wadud, an African-American feminist theologian and scholar of the Quran, who in the giddy days of 1994 and our fresh democracy, was invited by the forward-thinking Imam Dr Rashied Omar of the Claremont Main Road Mosque to deliver the Friday sermon, or khutbah talk, to a gender-mixed congregation, arguably a first in the modern world.

That bold, ground-breaking sermon, which used the metaphor of pregnancy to illustrate surrender to God, created a negative backlash, but also cracked open the doors to inclusive religious leadership in Muslim communities. Since then, Shaikh has published, with close friend and colleague, Professor Fatima Seedat, The Women’s Khutbah Book: Contemporary Sermons on Spirituality and Justice from around the World, which in addition to gathering 21 sermons from diverse Muslim women, contains at the back a template for creating a sermon.

“Having done over two decades of scholarship, my most recent work describes Islamic feminism as a friendship within tradition, characterised by a ‘radical critical fidelity’ defined by a radical love and commitment to Islam, as well as a radical critique of injustice,” Shaikh concluded.

“For Islamic feminists, tradition and religious knowledge are approached as open, dynamic and ongoing processes. Tradition and knowledge are not simply handed down to us from the past, they are also constantly being made in the present by believers who engage with the challenges of their time.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

The UCT Inaugural Lecture Series

Inaugural lectures are a central part of university academic life. These events are held to commemorate the inaugural lecturer’s appointment to full professorship. They provide a platform for the academic to present the body of research that they have been focusing on during their career, while also giving UCT the opportunity to showcase its academics and share its research with members of the wider university community and the general public in an accessible way.

In April 2023, Interim Vice-Chancellor Emeritus Professor Daya Reddy announced that the Vice-Chancellor’s Inaugural Lecture Series would be held in abeyance in the coming months, to accommodate a resumption of inaugural lectures under a reconfigured UCT Inaugural Lecture Series – where the UCT extended executive has resolved that for the foreseeable future, all inaugural lectures will be resumed at faculty level.

Recent executive communications

2025

2024

Professor Susan Cleary delivered her inaugural lecture on 14 March.

14 Mar 2024 - 5 min read2023

Prof Lydia Cairncross’s inaugural lecture provided a snapshot of the career path of a surgeon and community activist whose commitment to social justice means her work doesn’t end in the operating theatre.

02 Nov 2023 - 8 min read2022

Professor Linda Ronnie is in UCT’s Faculty of Commerce.

28 Sep 2022 - 6 min read2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016 and 2015

No inaugural lectures took place during 2015 and 2016.

.jpg)