‘GENESIS’ explores the space where black life persists

20 February 2026 | Story Nomfundo Xolo. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 10 min.

The stage at the heart of the Baxter Theatre Centre thrums, inhaling and exhaling as it comes alive with tension – iyabhonga!

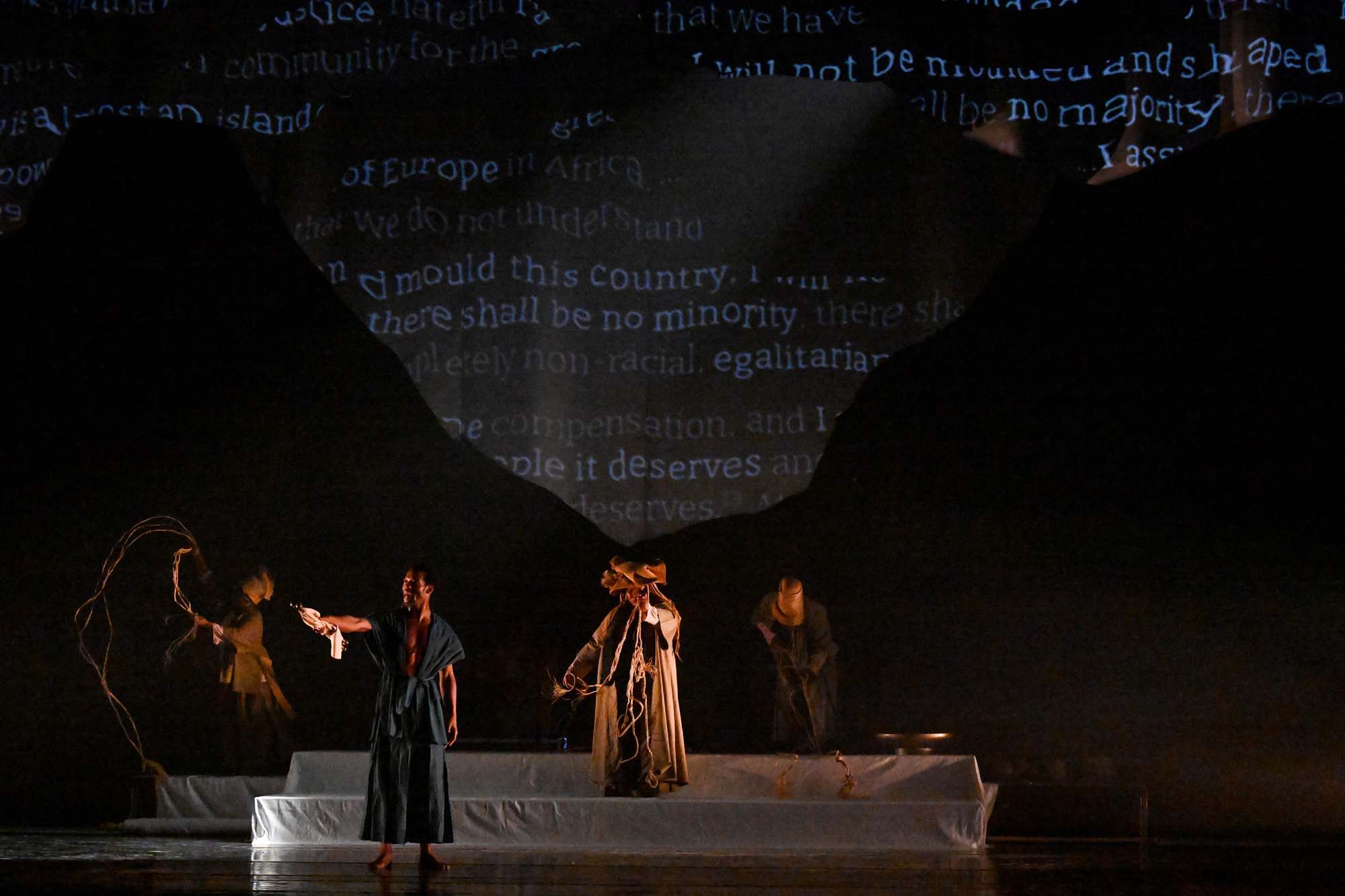

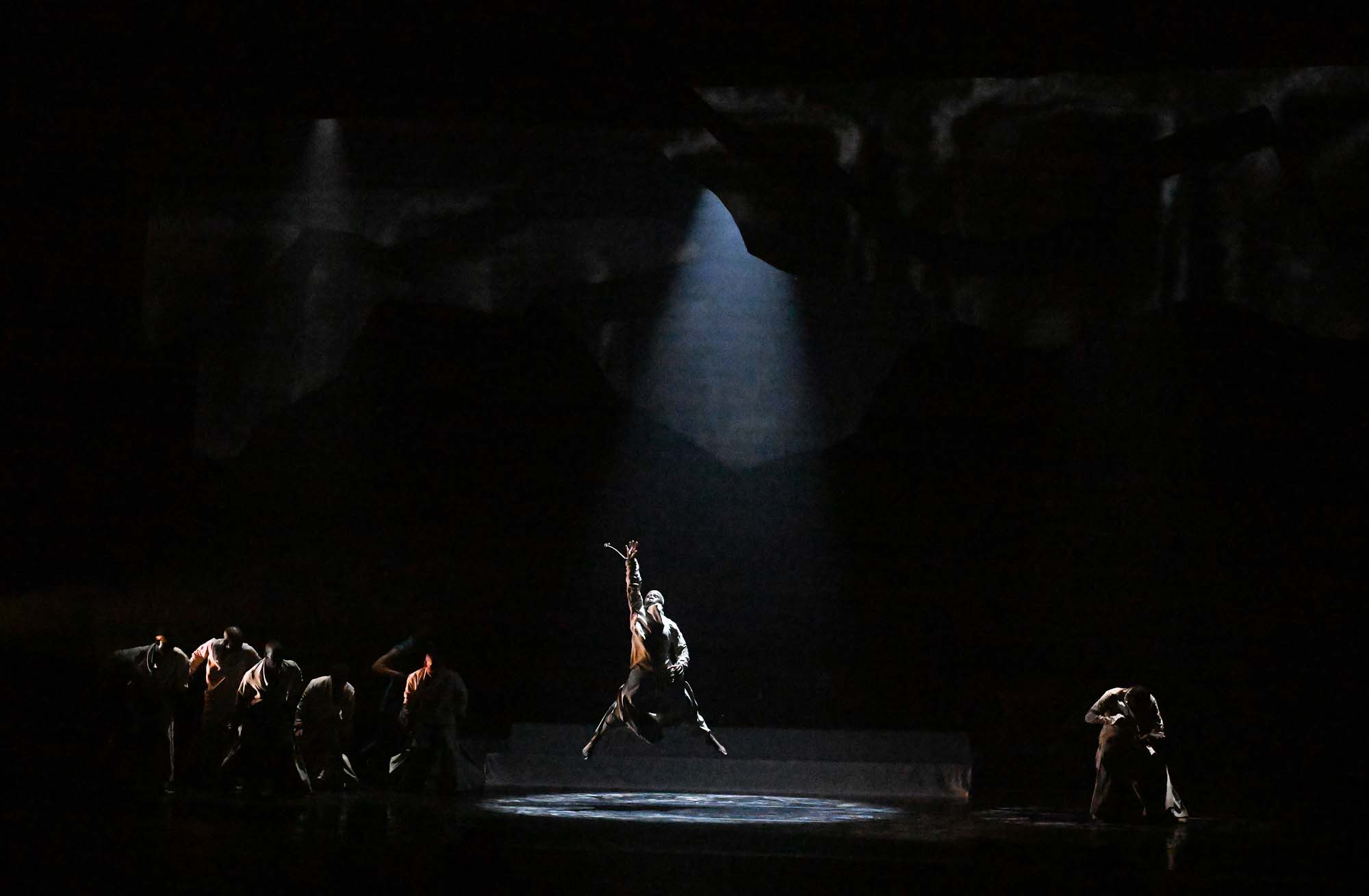

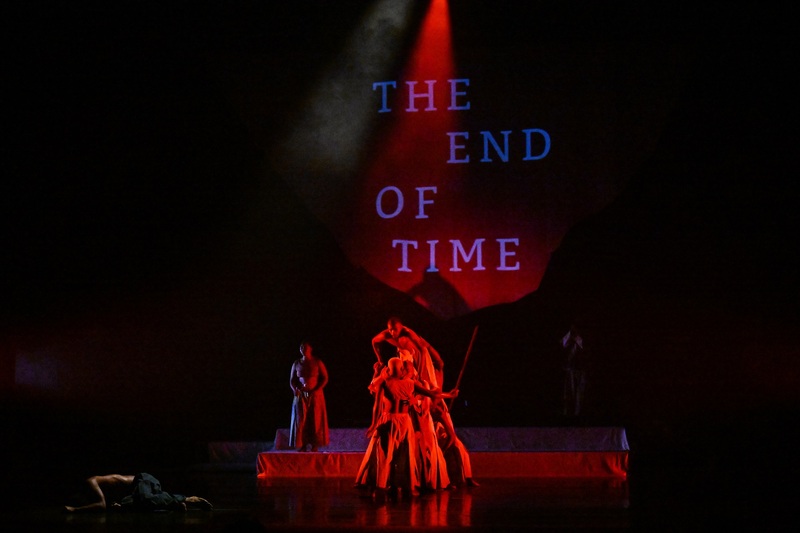

Lights dim into hues of red and cool blue. Voices chant, another whispers, and the haunting sound of ukubhonga persists. A curse unfurls: a warning, a prophecy, a declaration that time is not linear here.

This is where Gregory Maqoma, the director and choreographer of GENESIS-The beginning and end of time, begins his intense confrontation with history and the ghosts of greed and domination. As an audience, you witness the rupture and the pulse of something unsettled.

Set within the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) evolving transformation mission, the production operates as a form of embodied scholarship.

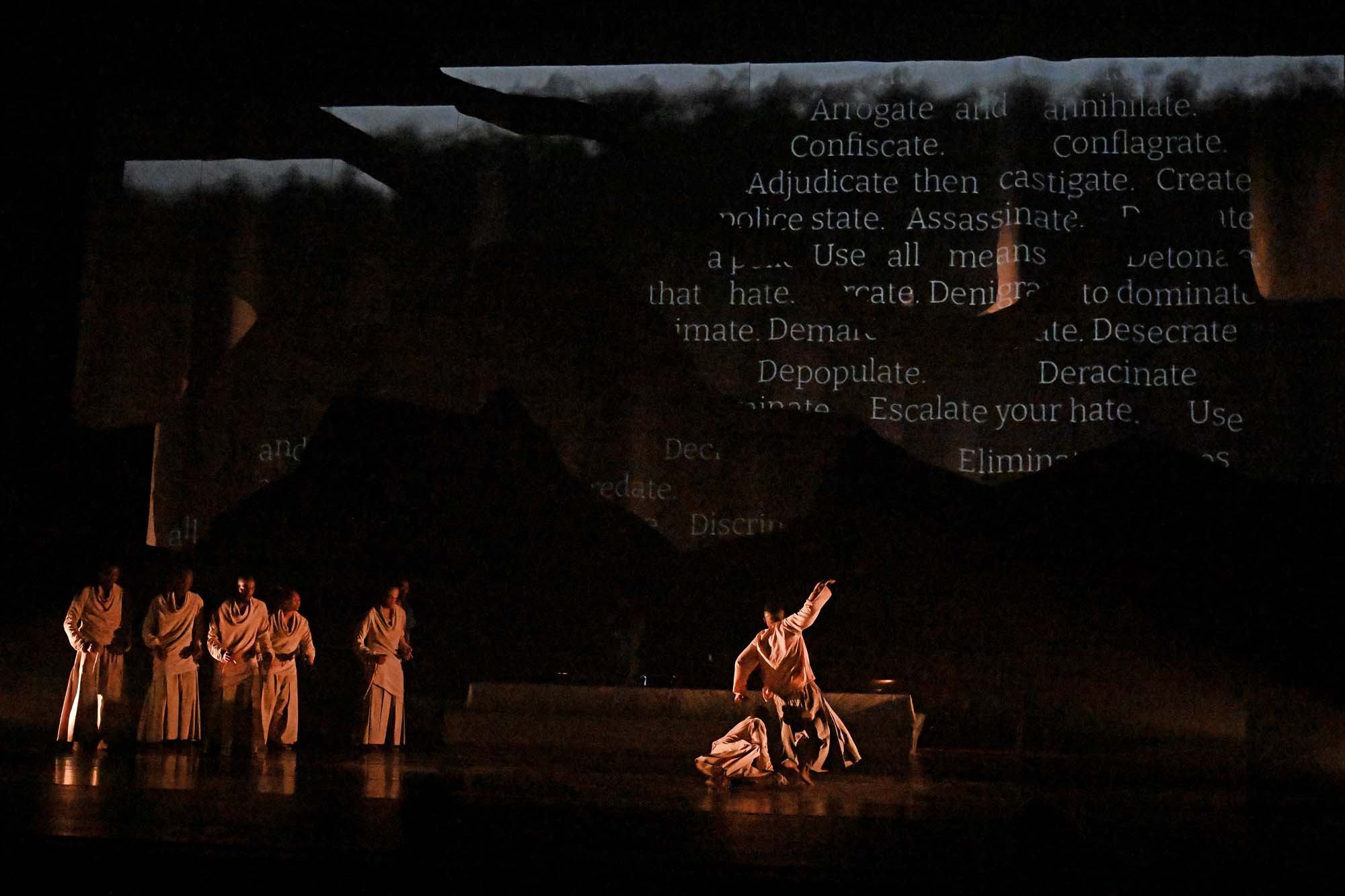

Through live music, ritualised movement and layered text and poetry delivered like proclamation – GENESIS, highlights South Africa’s unresolved questions about belonging, dispossession, memory and about whose pain is curated and whose is ignored.

The jolt into ‘time’

The first act is a stalking whisper at first and then quickly jolts you back to reality. “Blood, blood, red” – the voices and words written on the wall screamed.

Ukuthwala – a mythological practice associated in some histories with abduction, spiritual manipulation, and social control for long-term wealth, unfolds in the production as a metaphor. The ‘leader’, Anelisa Phewa, is seized and carried through chaos, through psychic and physical rupture, through the predatory authority of the witch, played by Anelisa ‘Annalyzer’ Stuurman.

She is not a villain easily undone. She dominates, extracts, pollutes. Her violence is brutal, her control generational.

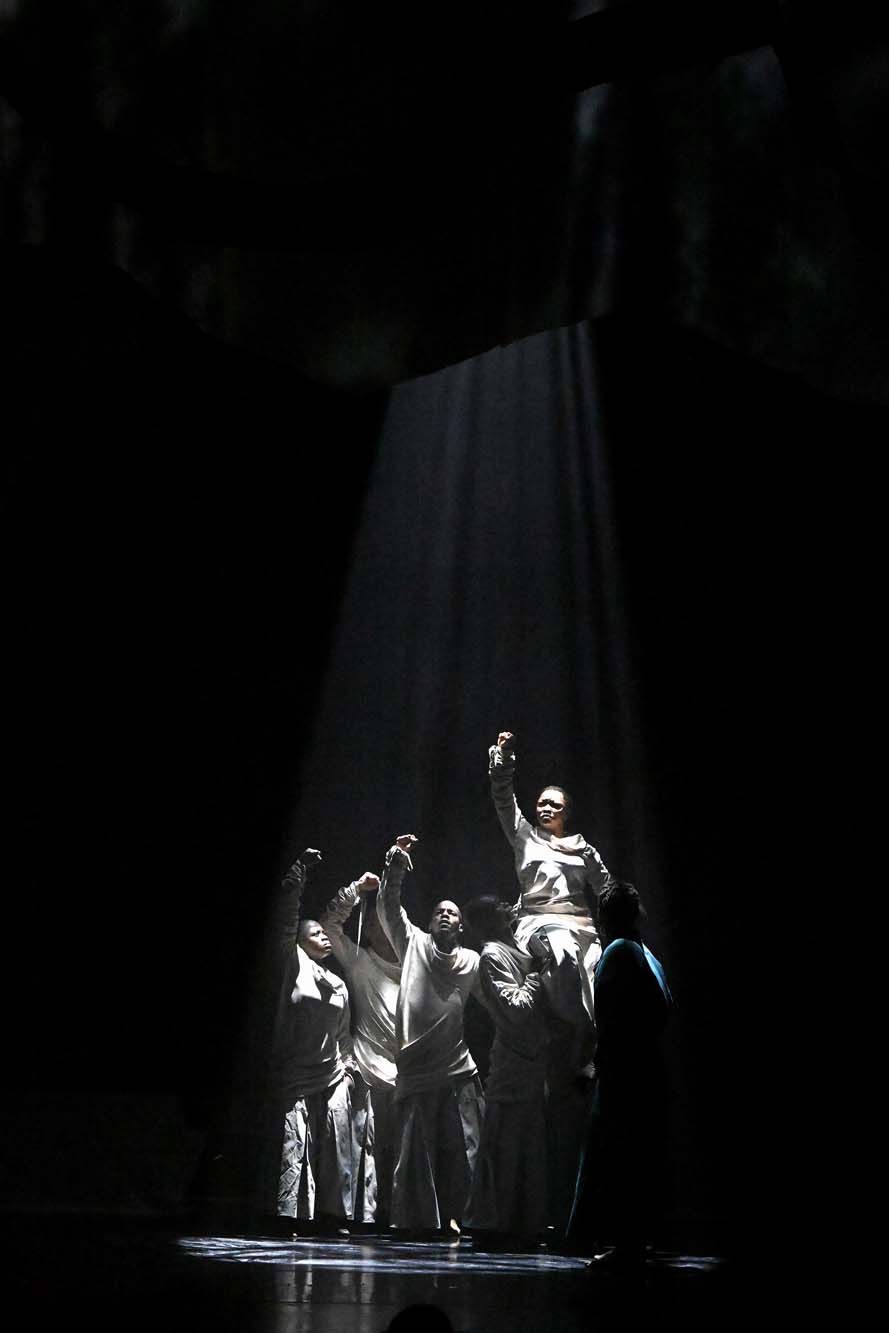

And yet she is contained – eventually betrayed by collective action: a riot becomes a boycott; a rupture becomes unity. Not a neat reconciliation, but a radical assertion that life – even after cycles of extraction – can find alignment. After all, this is the story of the diaspora. Of “colonialism’s half-life”, as described by Maqoma.

The performers chant: “Singabomkhathi, hhayi besikhathi”– not of time as minutes and hours, but of the cosmos, a dimension in which black life persists, expands and refuses erasure. Battered and landless mine workers move through the sound of shackles. “We are good migrants,” they declare, and the words hang in the air, equal parts dignity and indictment. The witch bursts into laughter.

Breath, spirit, and radical care

Breathing itself is ritual – a summoning of the leader thought lost. Umoya – air and spirit – functions as both instrument and sustenance. Ukubhonga, the witch’s roar, summons opposition; and in its contrast, the dancers’ synchronised breaths as they pump their fallen leader back to life enact revival – a reconstitution of life from collective care.

GENESIS is not a tale of colonial conquest; the coloniser’s body does not appear on stage. What lingers are the half-lives of oppression: inherited trauma, structural inequality, the afterimages of empire etched even into the cityscape beyond the theatre walls.

As Maqoma’s ensemble moves through the performance, they trace what he calls “a lineage of resistance” – Steve Biko’s consciousness; Frantz Fanon’s psychic mappings; and Aimé Césaire’s poetics of militancy.

The origin of a vision

The production has been five years in the making, though its emergence, Maqoma explained, was less a decision than a calling.

“You know, as I’ve been saying, we come from a single source, always, a vessel of knowledge, of being gifted. These gifts, these things, sometimes they come to me not only in dreams, but sometimes I stumble across a message from a reading. And that message will hit me so hard that I have no choice but to tap into it.”

That message, arriving at night, was the name of Bantu Stephen (Steve) Biko. It drew Maqoma inward and outward simultaneously – into the archive of Black radical thought and into the question of why those revolutionary ideas remain unheeded.

“What I kept hearing at night, like a refrain you cannot shake: ‘Biko, Biko, Biko.’ So, I started to visit the work of Biko, and then I found others who were like him, speaking the same language. And that’s how GENESIS emerged. It emerged because I was wondering: What is it that we haven’t really listened to? Why do we continue to be so stubborn and not learn from the revolutionary ideas left by those who walked before us?"

Maqoma described the formation of the creative team with the quiet certainty of someone who believes deeply in signs. Bongiwe “Mthwakazi” Lusizi brought spiritual and vocal connection to the messaging. Stuurman and Yogin Sullaphen created a sonic world that “drives the desire to be lost, to travel into space and time”.

“And the haunting voice of Xolisile Bongwana, who carries audiences from the furthest south into the deep north, into Timbuktu,” he added.

Why the Baxter?

Maqoma spoke of the Baxter with a warmth that goes beyond institutional gratitude.

“The Baxter holds a blanket for me, and everybody is on your side to succeed – and that’s the kind of space we need as artists, so that we can dream, be brave, and create. The Baxter has allowed me to do that, and they’ve given me time. It’s humbling. It’s a gift to be able to do what I do and to be able to teach others.”

“They speak to healing, remembrance and the reclamation of voice – ensuring that stories once silenced continue to find expression.”

That relationship is decades in the making. The Baxter opened its doors to all South Africans on 1 August 1977 – a defiant act at the height of apartheid, with a founding mandate to present the very best of South African performing arts, reflecting the stories and lived experiences of South Africans. For Baxter theatre marketing manager, Fahiem Stellenboom, GENESIS is exactly that mandate continuing. Of Maqoma, he said, “[He is] a true pioneer whose work is never merely performance – it is a profound, immersive collective experience that engages history, memory and humanity with rare depth.”

The conception of GENESIS, Stellenboom added, was “a natural and urgent next step, an opportunity to create bold new work in response to an increasingly chaotic and divided world, at a moment when audiences longed for art that could restore connection, provoke reflection and inspire hope”.

For Stellenboom, who was born in District Six and carries the lived memory of forced displacement, the production’s themes are not abstract. “Belonging and memory are central threads in my own journey. They speak to healing, remembrance and the reclamation of voice – ensuring that stories once silenced continue to find expression.”

The classroom beyond the stage

GENESIS arrived at a moment when UCT’s relationship with arts, identity and decolonial knowledge production is under active negotiation.

In the space between audience and performer, it translates into decolonial epistemology in motion. The work invites those watching to locate themselves in that reckoning. “The body archives,” Maqoma said. “It becomes a tool for awareness: a consciousness made tangible; a curriculum felt in the chest.”

For Xolani Rani, senior lecturer in African dance pedagogies at UCT, the production lands precisely where it is needed. “It sits well with the UCT decolonisation project,” he says, noting that he brought students to the show so the conversation could live beyond the classroom.

What GENESIS does, Rani explained, is make tangible what is so often only theorised. “When students see how these ideas can be articulated on stage, it creates a new awareness. They see what it means to embody these stories.” Drawing on black scholarship and Pan-Africanist thought as part of his daily teaching, Rani sees the production as both reawakening and resistance. “[It is a] pushback against the persistence of the Global North episteme as the default authority in academic spaces. It makes us feel less alone.”

Not resolution but a gathering

GENESIS refuses tidy resolution. The witch is defeated but not erased. Unity is proposed, never imposed. The political present is insistent: empire’s afterimages; oppression’s half-life; inequity’s imprint. The performance pauses audiences long enough to ask: How can we move forward while carrying unfinished justice?

In the end, unity is almost inevitable. With empires falling, again, and again, and again, what else remains? GENESIS does not answer this question cleanly.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.