In an age of incivility, humanity must lead

28 January 2026 | Story Myolisi Gophe. Photos Je’nine May. Read time 10 min.

In an era marked by rising global incivility, polarisation and dehumanisation, humanity – expressed through empathy, care, ethical leadership and social responsibility – is not a soft ideal, but an urgent necessity.

Speaking to the audience in a full lecture theatre on 23 January, internationally respected scholar Dr Lehana Thabane reflected on what he described as a growing global “incivility problem” and issued a clear challenge to universities, leaders and individuals alike: in a fractured world, humanity must become a deliberate practice rather than an assumed value.

Drawing on personal experience, global evidence and the enduring legacy of the late Professor Bongani Mayosi, the lecture argued that the erosion of civility is not confined to politics or social media, but has seeped into institutions meant to model care, dialogue and ethical leadership – including universities, hospitals and research environments.

“We do have a humanity problem in the academy.”

“We do have a humanity problem in the academy,” Dr Thabane, a professor in the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact at McMaster University in Canada, said plainly. “And it has a name: incivility.”

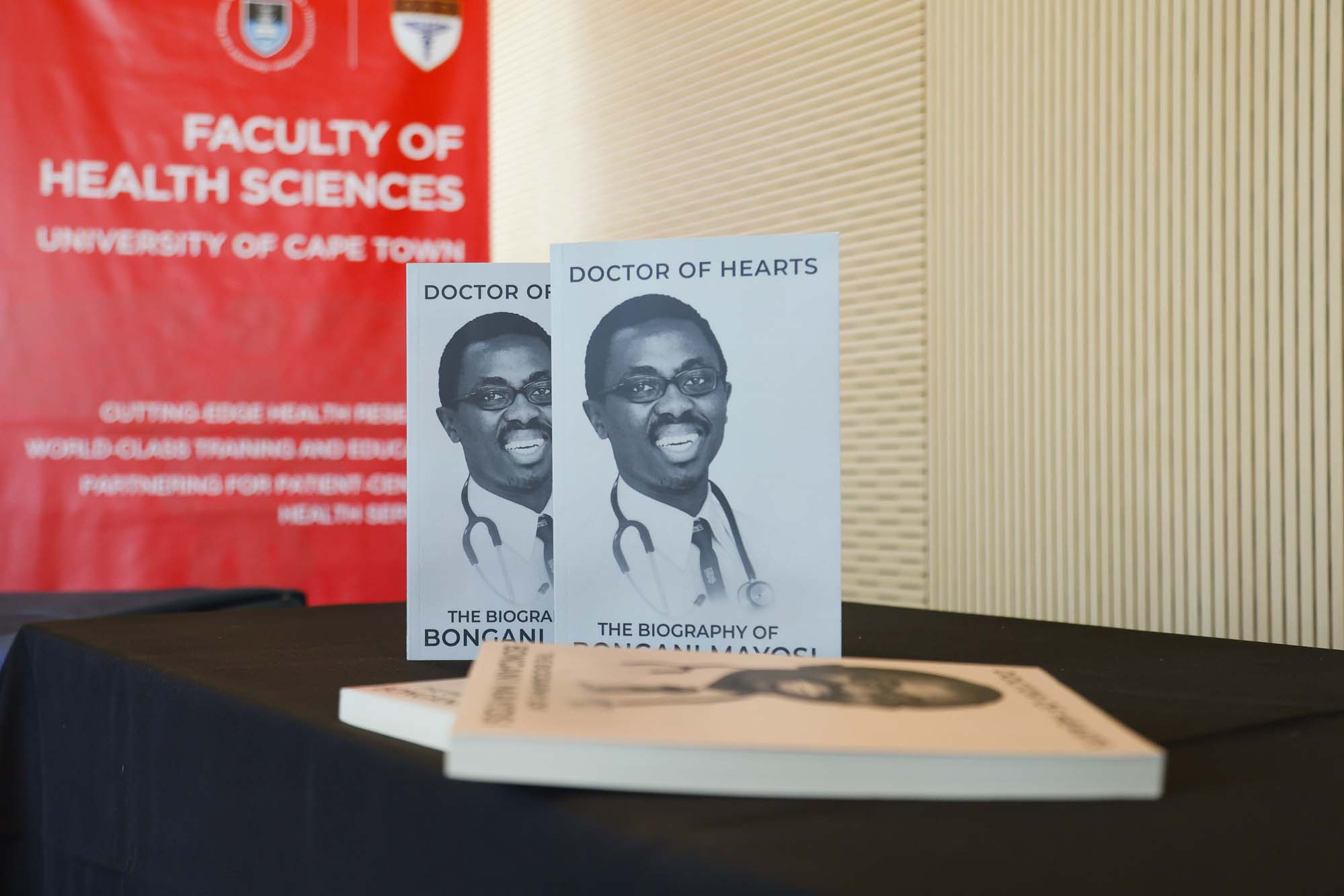

The lecture, titled “Fostering Evidence-based humanity in the academy and beyond”, drew huge interest from the members of the university community and the public alike, as it provides space to honour Professor Mayosi’s legacy and celebrate African scholarship. Mayosi was one of the leading South African cardiologists, an A-rated National Research Foundation scholar, and former dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS), whose work continues to influence generations of African students, academics, and researchers in the field of the health sciences.

A global problem with local consequences

According to Thabane, from Canada to Sierra Leone, South Africa to the United States, evidence shows that incivility – manifested through bullying, intolerance, hostility, racism, public humiliation and passive aggression – has intensified in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Universities are not immune.

He noted that such behaviour increasingly plays out in classrooms, seminars, research labs, leadership meetings and online spaces, affecting students, staff, faculty and institutional culture alike.

Beyond its moral cost, incivility carries serious consequences. It undermines individual well-being, corrodes organisational culture and compromises learning environments. In health sciences and education, its effects can be even more profound.

“We cannot give what we don’t have,” Thabane warned. “If we strip humanity from our institutions, it inevitably affects the care we provide to others.”

The lecture located this rise in incivility within broader social and geopolitical pressures: widening inequality, unchecked power dynamics, digital aggression, entitlement and chronic stress. In a world that has become deeply interconnected, conflict and cruelty no longer remain distant – they ripple across borders, institutions and communities.

Rather than treating humanity as an abstract concept, the Lesotho-born Thabane framed it as something deeply practical, relational and actionable. Humanity, he argued, is revealed in everyday choices: who we listen to, who we exclude, how we speak, when we remain silent – and why.

“It’s about how people make you feel,” he said. “And how you make other people feel.”

Thabane, the vice president of Research for St Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton and St Joseph’s Health System, appealed simultaneously to individuals, collectives and institutions, that systemic change begins with personal action – but must be sustained through organisational commitment.

“Can we address this? Should we? Must we? Yes, we must. But it requires commitment.”

Learning from Bongani Mayosi’s legacy

At the heart of his talk was a tribute to Mayosi – not only as a world-renowned scientist, but as a model of humanity in action.

He described Mayosi as someone whose presence changed people: inspiring them to dream more, care more, give more and become more. His legacy, he argued, lies not only in citations, awards or research funding, but in the lives he touched through kindness, humility, collaboration and mentorship.

“Many people say they became different after meeting Bongani,” he reflected. “I certainly did.”

Despite being ranked among the world’s top scientists, Mayosi’s humility remained unwavering. His global achievements never diminished his warmth, generosity or commitment to others – particularly young scholars and those navigating constrained or marginalised contexts.

“He was never limited by his location. But his success never affected his humanity.”

To translate Mayosi’s legacy into action, Thabane offered seven guiding principles – framed deliberately as verbs, emphasising that humanity requires doing, not just believing.

“Kindness doesn’t just help the person receiving it. It helps the person witnessing it, too.”

These included: living with intention, volunteering in communities, practising humility, being a friend, choosing kindness, collaborating generously and mentoring others.

Each principle was illustrated through examples from Mayosi’s life – from his deliberate approach to relationships and leadership, to his quiet but extensive volunteerism across global health, academic publishing and international advisory bodies.

Importantly, Thabane emphasised that these actions are supported by evidence. Research shows that intentional living, volunteering, collaboration and mentorship not only benefit institutions and communities, but also improve mental health, physical well-being, productivity and professional fulfilment.

“Kindness doesn’t just help the person receiving it,” he said. “It helps the person witnessing it, too.”

The lecture also resonated strongly with African humanist traditions, particularly the philosophy of ubuntu – the idea that a person becomes human through other people.

Mayosi embodied this ethos naturally, not as political posture but as a way of being. His life demonstrated that individual actions, when aligned with collective values, can create movements rather than moments.

“We exist as part of a collective. And when individual actions align, they become collective change. You don’t have to do everything. But you can do one thing.”

Tribute

In her welcome address, Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Transformation, Student Affairs and Social Responsiveness Professor Elelwani Ramugondo, who was standing in for the vice-chancellor, described the event as deeply meaningful for UCT and for all whose lives were shaped by Mayosi’s leadership and humanity, noting that the annual lecture is “not only an award, it is a commitment” to the values that defined Mayosi’s life and work.

She paid tribute to Mayosi as a scholar who led “with clarity, courage and caring”, and who believed that African institutions should “set the agenda to address local needs while contributing knowledge to global institutions”. At a time when universities face rising expectations to confront inequality and develop ethical leaders, she reminded the audience that, as Mayosi often said, “excellence is nothing without humanity”.

“Excellence is nothing without humanity.”

The dean of the FHS, Professor Lionel Green-Thompson, said the lecture was a reminder that universities need not choose between rigour and care, noting that the most meaningful work emerges when “evidence, excellence and high standards” are held together with generosity, accessibility and deep humanity. This approach, he said, was embodied in the leadership and mentorship of Mayosi.

Speaking on behalf of the Bongani Mayosi Foundation, Mlamli Booi described the annual lecture as both an act of remembrance and a call to action, noting that Mayosi believed deeply that “our knowledge must matter” and that scholarship should confront inequality.

Booi highlighted the foundation’s work, including student awards, fundraising initiatives such as the annual golf day, and the newly launched Bongani Mayosi Graduation Fund, which helps financially constrained students complete their studies. He also announced a new fully funded Oxford University master’s scholarship for African students, describing it as a powerful continuation of Mayosi’s vision to expand African academic excellence globally.

During the final leg of the programme, the foundation also named the recipients of the Bongani Mayosi National Medical Students Academic Prize from six universities across the country.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.