Reflecting on 10 years of Rhodes Must Fall

05 September 2025 | Story Stephen Langtry. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 6 min.

On 28 August, the Institute for Creative Arts (ICA), in collaboration with the Rhodes Must Fall Feminist Collective and the African Gender Institute (AGI), hosted the first of three public dialogues, marking a decade since the eruption of the Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) movement at the University of Cape Town (UCT).

The dialogue series, “Radical Pasts, Decolonial Futures: Reflecting on 10 Years of Rhodes Must Fall”, is both a commemoration and a re-engagement with the living legacies of Fallism, situating feminist organising, art, and intellectual praxis at its centre.

The opening conversation, Intergenerational Feminist Organising – Tracing Lineages, Seeding Futures, convened at the Centre for African Studies (CAS) Gallery on UCT’s upper campus. The panel consisted of thinkers and organisers across generations, underscoring the RMF’s story as an ongoing struggle, instead of a closed chapter.

Launched in March 2015 when the statue of Cecil John Rhodes was pelted with excrement, the RMF movement sparked a wave of radical student activism across South Africa and beyond. At UCT, the movement catalysed conversations about institutional racism, colonial legacies, and the need for transformation in higher education. Its call for decolonisation reverberated globally, inspiring sister movements such as #FeesMustFall and echoing in campaigns at Oxford University. Yet 10 years later, as this dialogue series underscores, the RMF movement was never simply about the removal of a statue. It was and remains a political and intellectual project concerned with dismantling structural inequalities, producing decolonial knowledge, and centring marginalised voices, particularly those of black women and queer activists.

The Feminist Collective within RMF played a vital role in pushing the movement toward accountability, inclusivity, and feminist praxis. As the first dialogue emphasised, women and queer activists were often at the heart of the work but sidelined in official narratives. This series aims to correct that erasure, foregrounding feminist organising as both a historical lineage and a pathway to future struggles.

Revisiting Rhodes Must Fall’s legacy

Professor Zethu Matebeni, sociologist, activist, and South African Research Chair in Sexualities, Genders and Queer Studies at the University of Fort Hare, reflected on the intellectual and emotional labour that queer and feminist activists carried within RMF. “That was a very difficult time … to put yourself in a space where you are so undermined, and you keep pushing to say, ‘Here I am and I am doing all these amazing things with my people. And this space can be better by recognising me and us’.” For Professor Matebeni, the struggle was not only about challenging institutional structures but also about carving out recognition in a deeply hostile environment.

Professor June Bam-Hutchison, anti-apartheid educator and director of the Centre for Education Rights and Transformation at the University of Johannesburg, situated the RMF movement within longer histories of resistance. “If you remove Rhodes, what were you saying? What’s the counter-archive? What is that dialogical archive?” she asked, emphasising that decolonial struggle requires not just tearing down symbols but building intellectual and cultural alternatives. Reflecting on her 40-year relationship with UCT, beginning when she was one of only a handful of black students, she described the movement as “a moment of great liberation but also sadness”. She added that she carried “gratitude in my heart for the Rhodes Must Fall movement, the Feminist Collective in particular”, recognising their role in carrying forward feminist intellectual traditions.

Onalenna Sebetlela, legal scholar and community organiser, drew attention to the ongoing structural challenges feminist organisers face within South Africa’s legal and institutional frameworks. Performance artist and cultural worker Zizi Masizana reminded the audience of the centrality of art to RMF’s politics.

For Alex Hotz, an RMF activist and current South African lead coordinator for WoMin African Alliance, the movement represented both a personal and collective turning point. “It was a real journey and space to grapple with many political questions,” she said. “It was a fundamental moment for my own political awakening and growth as a feminist; as a black young person.” Hotz noted the unfinished business of the struggle: “[We need] to think about where we are at now and the role of the university, and how we begin to shape or rewrite the narrative or challenge the narratives that have been written about us; in many instances without us.”

Together, their conversation traced lineages of feminist organising from anti-apartheid struggles to Fallism and beyond, while acknowledging fractures, tensions, and the possibilities of sustaining radical organising within institutions.

Feminist narrative justice

At the heart of the discussion was the principle of feminist narrative justice. Speakers reiterated that feminist contributions to RMF were not supplementary but foundational. The insistence on centring black women’s experiences, queer voices, and intersectional approaches shaped the movement’s direction, even when these interventions generated conflict. Some recalled the challenges of holding male comrades accountable for reproducing patriarchal behaviours within the movement; others reflected on how the intellectual and emotional labour of women and queer activists was often undervalued.

By revisiting these tensions, the dialogue created space not only to celebrate past victories but also to critically engage with the shortcomings of RMF and similar movements. The panellists and audience reflected on the future of feminist and decolonial organising in South Africa.

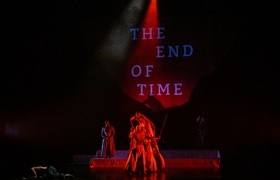

The upcoming dialogues, scheduled for 18 September and 2 October, will continue these explorations. Dialogue two will deepen engagement with feminist intellectual praxis, while dialogue three will spotlight artivism as a strategy for resistance and world-making.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.