UCT at the forefront of landmark discovery on early human genetics

02 June 2025 | Story Staff writer. Photo Victor Yan Kin Lee. Read time 4 min.

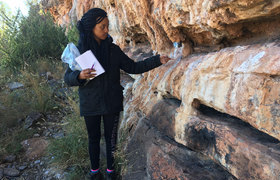

In a scientific first, a team led by researchers from the University of Cape Town (UCT) and the University of Copenhagen has used ancient proteins to uncover biological sex and hidden genetic variation in Paranthropus robustus – a close, extinct cousin of modern humans.

The groundbreaking study, published in Science journal, analysed two-million-year-old protein traces extracted from fossilised teeth unearthed in South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind.

The discovery delivers some of the oldest human genetic data ever recovered from Africa and challenges long-standing assumptions about one of our early hominin relatives. “Because we can sample multiple African Pleistocene hominin individuals classified within the same group, we’re now able to observe not just biological sex, but for the first time genetic differences that might have existed among them,” said the study’s co-lead, Dr Palesa Madupe.

Dr Madupe, a research associate at UCT’s Human Evolution Research Institute (HERI) and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute, is part of a powerful African cohort transforming palaeoanthropology from within. UCT’s HERI played a central role in the research, with co-director, Professor Rebecca Ackermann, as a senior author, and contributions from co-director, Robyn Pickering, and multiple HERI research associates.

“Enamel is extremely valuable because it provides information about both biological sex and evolutionary relationships.”

The team used cutting-edge palaeoproteomic techniques and mass spectrometry to identify sex-specific variants of amelogenin, a protein found in tooth enamel. Two of the ancient individuals were conclusively male; the others, inferred through novel quantitative methods, were female.

“Enamel is extremely valuable because it provides information about both biological sex and evolutionary relationships. However, since identifying females relies on the absence of specific protein variants, it is crucial to rigorously control our methods to ensure confident results,” explained paper co-lead and postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Protein Research, University of Copenhagen, Claire Koenig.

Unexpectedly, another enamel protein – enamelin – revealed genetic diversity among the four individuals. Two shared a particular variant, a third had a distinct one, and a fourth displayed both.

Understanding origins

Co-lead and postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute Ioannis Patramanis said: “When studying proteins, specific mutations are thought to be characteristic of a species ... we were thus quite surprised to discover that what we initially thought was a mutation uniquely describing Paranthropus robustus was actually a variable within that group.”

This revelation forces a rethink of how ancient hominin species are identified, showing that genetic variation – not just skeletal traits – must be considered in understanding their complexity. “With this data, we shed light on how evolution worked in the deep past and how recovering these mutations might help us understand genetic differences we see today,” added Madupe.

Paranthropus lived in Africa between 2.8 and 1.2 million years ago, walking upright and likely coexisting with early members of Homo. Though on a different evolutionary path, its story remains central to understanding our origins.

This study not only advances palaeoproteomics in Africa but also highlights the vital role of African scholars in rewriting human history. “As a young African researcher, I’m honoured to have significantly contributed to such a high-impact publication as its co-lead. But it’s not lost on me that people of colour have a long journey to go before it becomes commonplace – more of us need to be leading research like this,” said Madupe.

HERI at UCT is actively leading that shift. The institute has launched programmes introducing palaeoproteomic techniques to a new generation of African scientists and is expanding training across the continent. “We are excited about the capacity building that has come out of this collaboration. The future of African-led palaeoanthropology research is bright,” concluded Professor Ackermann.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.