Research and Internationalisation

12 November 2021 Read time >10 min.

Professor Sue Harrison

Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Research and Internationalisation

As COVID-19 spread across the globe in 2020 our focus moved to ensuring that we could live and work within the uncertainty of a world in lockdown and the constraints of a (largely) virtual campus. As a research-led, residential university, the effects of lockdown were felt profoundly as staff and students moved off campus, out of laboratories and lecture rooms and away from essential support systems.

Our immediate goal was to move all undergraduate and taught postgraduate curricula online, to facilitate moving the research of postgraduate students, postdoctoral fellows and researchers online wherever possible, and to ensure the COVID-19 compliant operation of ongoing laboratory- and site-based COVID-19 research. Importantly, we needed to establish communications and support systems that allowed students and staff to balance conflicting demands as homes became workplaces. All activities through which research staff were in physical research locations were urgently reviewed to ensure COVID-19 compliance.

As we adjusted to the “new normal” of virtual interfaces, virtual libraries and virtual collaborations, our focus was to keep the research enterprise healthy: relevant to community needs, pushing knowledge boundaries, and driving innovation and excellence. Balance was critical. We needed to sustain world-class research while minimising risks to the community, especially where research projects involved human subjects directly. I am very grateful to the members of our research task team who helped facilitate research during the hard lockdown and to reinvigorate it as we have returned to a low-density campus under strict COVID-19 protocols.

It was heartening to see how quickly we pivoted. Health science researchers undertook truly innovative COVID-19 research in epidemiological studies, drug trials, clinical studies, COVID-19 diagnostics and reagents, vaccine development, vaccine efficacy trials, interactive impact of vaccines with TB and related diseases, medical devices, and personal protective equipment, among others. Across campus, many of our researchers pivoted to COVID-19-related research, including research on economic impact and the impact on families, learning in the school curriculum, parenting and child support, communication, and on providing effective oxygen delivery and sanitation systems.

Funding became a priority as external funders felt the effects of the pandemic and projects were delayed by constraints on movement and activities. As the university went into lockdown, I assembled a task team to identify routes to support soft-funded research. The scale of this challenge was significant: 1 000 soft-funded researchers depend on external research contracts and their work is critical to our output, particularly that focused on quality of life and societal impact. We are grateful to the support of our external funders in the light of the disrupted research environment and to our Council who made relief funding available to support soft-funded researcher salaries on a needs basis driven by lockdown. We continue to focus on securing appropriate funding in this funding-constrained environment.

Despite tough conditions, we celebrated many highlights in 2020 and I note some of them here:

- UCT was again ranked Africa’s top university by leading international rankings.

- The total value of research contracts signed in 2020 was R2.2 billion while our research income exceeded R1.6 billion.

- UCT hosted 25% (32) of South Africa’s National Research Foundation A-rated scholars and 39% of the prestigious P-rated young scholars.

- UCT researchers held 42 chairs (17%) in the South Africa Research Chairs Initiative.

Although 2020 presented huge challenges, it gave us an opportunity to re-examine how we do things and support research. Our aim is to find innovative and agile approaches to building our research strengths and extending its impact.

At last year’s amalgamated Research Symposium and Research Function, presented on a virtual platform, we had an opportunity to do some of that thinking. We looked at shaping UCT’s research and postgraduate study to position us for Vision 2030, including thinking through aspects of what a PhD might look like from a global south perspective, where Africa has a critical voice.

We continue to focus on expanding our research networks strategically, diversifying our research funding, and embedding and leading new “open science” norms with the aim of making scientific research accessible to all levels of society.

Looking back at 2020, I have only the highest praise for our staff and students for their resilience and commitment in the face of immense challenges. We learnt a huge amount and will continue to be alert to opportunities for growth and renewal in 2021 as we design our path towards implementing Vision 2030 and targeting the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 in alignment with the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Trains least safe transport for women

Although rail offers the cheapest daily commute, trains are the most dangerous mode of public transport for South African women, as reported in an award-winning paper by transport engineer Professor Marianne Vanderschuren.

The co-authored paper, “Perception of Gender, Mobility and Personal Safety: South Africa Moving Forward”, published in the Transportation Research Record Journal, won the United States Transport Research Board’s annual Charley V Wootan Award.

Her findings have significant implications for the country and call for more nuanced public transport policies.

In South Africa more women than men (26.5% vs 23.5%) use public transport, and more women (31% vs 27%) travel to work. In line with international literature, South African women make 2% more “care trips” (taking children to school, clinic visits, etc), and 8% more shopping trips.

“It has been established that transport planning is male dominated. More guidance is needed for transport planners and city authorities to plan better and more gender-sensitive networks and services,” said Vanderschuren, who is based at the Centre for Transport Studies in the Faculty of Engineering & the Built Environment.

Women’s priorities must be met if urban transport is to cater for the needs of the entire population. Currently, transport is not gender neutral and is in sharp contrast to the country’s progressive Constitution, she added.

“Treating communities as homogenous is a major flaw in current policies and practices ...”

The commuter safety issue must also be viewed against the South African National Development Plan’s 2030 vision, which includes improved access to economic opportunities, social spaces and services by bridging geographic distance affordably, reliably – and safely. Harassment is a major concern for women train commuters.

“Treating communities as homogenous is a major flaw in current policies and practices, which don’t recognise women’s and men’s different needs and patterns of mobility and accessibility.”

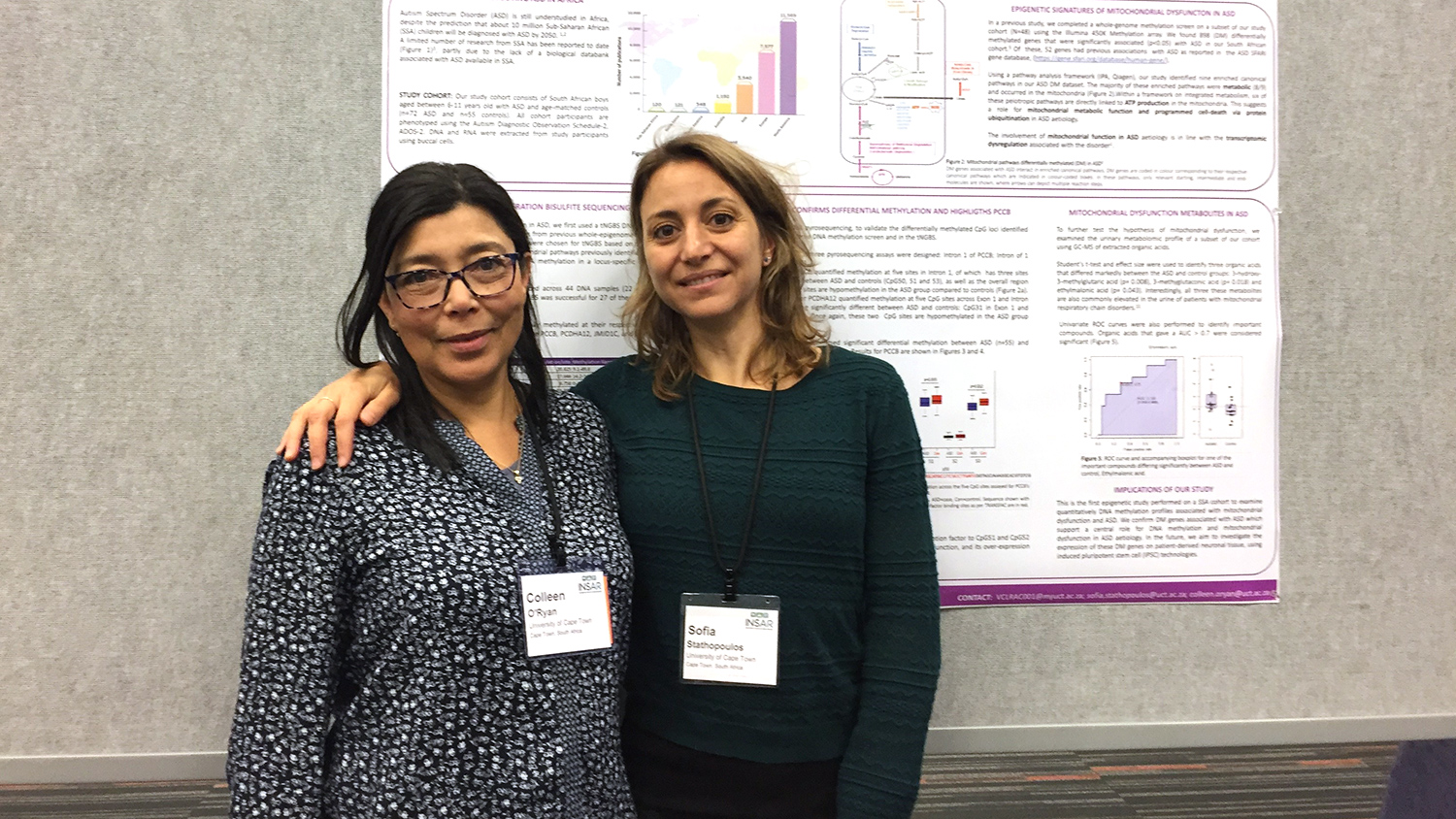

Epigenetic autism study breaks new ground

Dr Colleen O’Ryan’s project to research the genes associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in a cohort of South African children resulted in a groundbreaking paper, “DNA methylation associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in a South African Autism Spectrum Disorder cohort”, published in the Autism Research journal.

This showed that South African children with autism were more likely to have mitochondrial disorders.

Dr O’Ryan established and heads the Genetic Autism Cape Town Research Group within the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology.

She said the paper is unique because it was the first from a South African research group examining South African children using a whole genomic approach, as well as one that used an epigenetic (methylation) approach.

O’Ryan’s interest in the field stemmed from her honours year in medical biochemistry under the supervision of chemical pathologist Professor Eric Harley, who ran a laboratory looking at rare inherited mitochondrial diseases.

After completing her PhD in evolutionary genetics and genetic relatedness of African rhinos, O’Ryan established herself as an expert in population and evolutionary genetics. She later developed a keen interest in behavioural genetics and was subsequently asked to assist on a study of individuals with ASD. Clinical evidence showed individuals with autism were more likely to have mitochondrial disorders.

O’Ryan remembered that Harley’s group had conducted research on mitochondrial diseases where individuals have muscle weakness, intellectual disabilities and behavioural challenges. She noticed similar genes in her autism study.

After further investigation they found a metabolic signature that was indeed different between their ASD and control groups. This showed that in a South African cohort of children, DNA methylation is different between children with and without autism, and that this methylation is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in ASD.

Their findings have opened up a range of new study possibilities for emerging researchers.

Biochemistry breakthrough for UCT researchers

In a global first, three UCT researchers visualised – at a resolution close to that of individual atoms – the intact active site of a commercially important biological molecule.

Dr Jeremy Woodward, Dr Andani Mulelu and Angela Kirykowicz gained novel insights into the structure of a group of enzymes known as nitrilases, which have enormous biotechnological potential.

“We’re not just following nature. We are being inspired by it and altering what it can do. We are able to produce brand new enzymes,” said Mulelu, who is a research scientist at UCT’s H3D Drug Discovery and Development Centre.

The breakthrough research holds the potential for long-lasting and widespread impacts on everything from manufacturing better medicines to cleaning up pollution.

“We found it really exciting to be able to open up the mechanism of this biological machine and understand it.”

“Enzymes produce all the chemicals in plants and animals that allow them to survive. They are the chemical factories of the cell,” said Woodward, principal investigator in UCT’s Structural Biology Research Unit. “We found it really exciting to be able to open up the mechanism of this biological machine and understand it.”

The UCT team investigated the structure of the enzymes using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) – a technique that can determine the structure of large biological molecules. It helped them to produce the first high-resolution visualisation of a cryo-EM protein structure in Africa.

The discovery was the culmination of years of work and was made possible through access to the electron Bio-Imaging Centre facilities at the United Kingdom’s Diamond Light Source Synchrotron and a grant from the Global Challenges Research Fund’s Synchrotron Techniques for African Research and Technology (START) programme, set up to build partnerships between scientists in Africa and the United Kingdom.

The potential for using nitrilases to make pharmaceuticals could revolutionise the way drug resistance is approached in Africa and other developing countries.

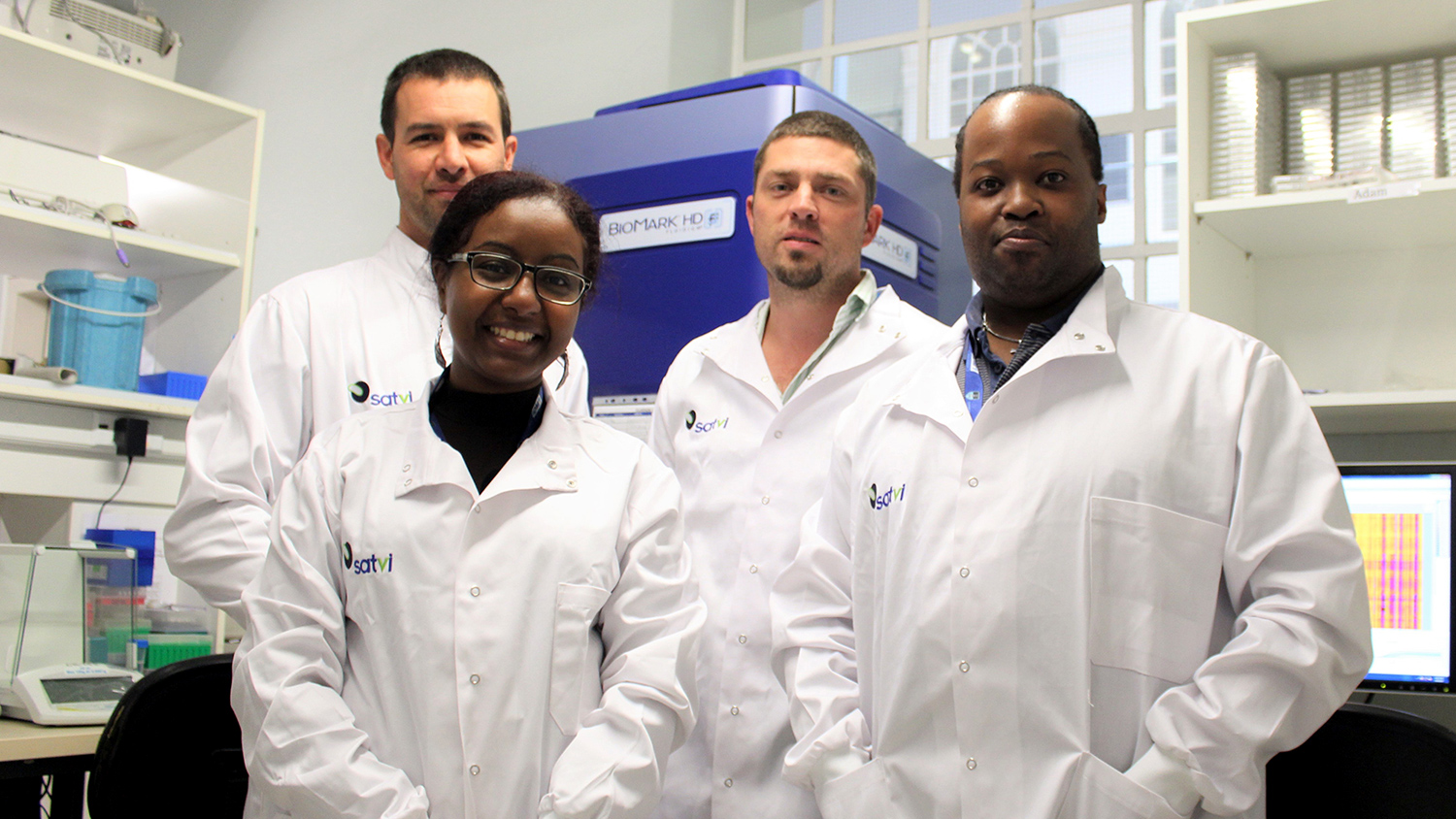

New multifunctional TB blood test validated

Researchers from the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI) at UCT and the Center for Global Infectious Disease Research – Seattle in the United States, and a large consortium of collaborators, developed and validated a new, simple blood-based test that has the potential to serve multiple functions in the fight against tuberculosis (TB).

The test, called RISK6, can identify healthy individuals who are at risk of developing TB as well as people with subclinical or clinical disease, and contributes to understanding how well a patient would respond to treatment. It has been validated in seven cohorts across two continents.

The researchers also showed that RISK6, which can be applied to capillary blood collected by finger prick, could be developed into a rapid, finger-prick blood-based test device for use at points of care.

This advance, published in the journal Scientific Reports, paves the way for studies to evaluate and implement the test in community and primary care settings.

“Most people with TB are identified too late, when they have already passed the bacterium to family and friends.”

“Finding everyone with TB, so that they can receive antibiotic treatment to get better and so that they do not infect others, is critically important,” said Professor Thomas Scriba, deputy director of immunology at SATVI.

“Most people with TB are identified too late, when they have already passed the bacterium to family and friends.”

The World Health Organisation’s Global TB Report 2019 estimated that more than 1.7 billion people are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis globally, of whom 10 million developed TB and more than 1.4 million died in 2018.

Current diagnostic tools for TB rely on detecting the bacterium in sputum. This means it is possible to administer these tests only to people with advanced TB and who can produce sputum samples.

Amplifying the voice of women struggle heroes

College of Music researcher Dr Janie Cole and UCT Libraries Special Collections collaborated to build a rare collection of filmed oral testimonies, music and personal documents by former female political prisoners and prison guards.

The Malibongwe Women’s Archive project communicates a hitherto unseen female perspective on the struggle against racial discrimination and the oppression of women during the anti-apartheid struggle (1948–1994). It was awarded launch funding from the Carl Schlettwein Foundation.

Dr Cole said the cultural-heritage preservation project would provide a new perspective on the standard liberation struggle narrative by embracing gender issues that have been historically overlooked.

The goal of the project is to collect interviews, original music tracks and items for a personal archive (photos, diaries, letters, etc) that will chart the active role of women against apartheid.

The Malibongwe Women’s Archive comes as an outflow of Cole’s ongoing research exploring the critical role music played as a force of resistance, protest and survival in apartheid prisons. This has also underpinned her work as founder of the Music Beyond Borders platform for cultural heritage preservation, and signalling the importance and power of survivor and perpetrator testimony for creating a compelling voice for raising awareness and education.

Time was a critical factor in the project as the now elderly apartheid struggle heroes were dying, said Cole.

Apart from its cultural, historical and political significance, the Malibongwe Women’s Archive is set to be an educational treasure chest for future generations.

Centre has ‘Africanised’ neuroscience

The launch of UCTʼs multidisciplinary Neuroscience Centre, established for inter- and cross-disciplinary research and fast-tracking novel treatment options for neurological disorders, was a significant step towards “Africanising” neuroscience in South Africa.

A first of its kind on the continent, the centre was established in partnership with the Western Cape Provincial Government. It is housed at Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH) and will strengthen the existing partnership with UCT.

It has been established specifically to address South Africa’s high burden of disease in mental and neurological disorders.

The facility boasts state-of-the-art technology and facilities and brings together scientists and academics in neuroscience to integrate and improve patient care, research, teaching and training, as well as advocacy.

Speaking at the launch, MEC for Health in the Western Cape Dr Nomafrench Mbombo said the centre would provide “tangible” work towards decolonising expertise in neuroscience and in the country’s healthcare sector.

Vice-Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng said the centre was an example of how the university brought world-class expertise into Africa to build local capacity.

Children, pests and poisons: a toxic layering

A multidisciplinary group of researchers is working to understand why growing numbers of children in informal settlements are being accidentally poisoned by illegal pesticides. Their work is an example of a burgeoning health–humanities approach in the global south.

Street pesticides are either legal agricultural products that are repurposed by informal traders and sold illegally in urban townships around Cape Town or they are packaged in other countries and not registered for legal use in South Africa. Residents buy these products to protect their homes and children from pests, such as rats and cockroaches, pervasive in low-income communities.

Unfortunately, these highly toxic substances are also being consumed accidentally by children, said global pesticides authority Professor Andrea Rother, head of the Environmental Health Division in the School of Public Health and Family Medicine.

Professor Rother worked with medical anthropologist Associate Professor Susan Levine across UCT’s faculties, as well as with the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital Poison Unit, public health officials and Associate Professor Fritha Langerman, of the Michaelis School of Fine Art.

The team identified various pesticides sold by informal vendors, including Aldicarb – a highly toxic agricultural pesticide for killing nematodes (worms). The study results were influential in banning Aldicarb in South Africa.

Communications are essential to this battle. A reference group of environmental health specialists and practitioners, anthropologists, doctors and students produced flip charts for health workers and developed training workshops.

They are working with hospitals and forensic pathologists at mortuaries to underscore the need for capturing detailed case notes that include the exact substance that caused the poisoning.

PhD researcher recreates 111-year-old fishing survey

For his PhD project, marine scientist Dr Jock Currie recreated a demersal fisheries survey, first undertaken along the Agulhas Bank 111 years ago. The ambitious task involved finding an old trawler and weaving the manila hemp nets used back then.

Currie’s careful re-enactment of the past produced a rare snapshot of fisheries on the Agulhas Bank more than a century ago and how they compare today after decades of industrial fisheries and climate change. The results were published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

Between 1897 and 1904, the Agulhas bank was surveyed by the government research fishing vessel, the SS Pieter Faure. Currie resurveyed three sites in 2015 using old-time fishing methods and reproductions of the original manila hemp trawl gear, a Granton otter trawl net. He found an old side trawler and refitted it with the net and flat wooden trawl doors of the kind used back then.

Comparative records using accurate historical baseline data are crucial to managing fisheries and ecosystems. It took careful interpretation of relevant literature and photographs to plan the design, dimensions, materials and methods of fishing. All these factors influence the fishing performance and catch because of the shape, size and behaviour of the fish netted.

After 111 years, the resurvey revealed drastically transformed catches. Historical catches were dominated by kob, panga and east coast sole. Those species constitute a minor component of modern assemblages. These are now predominantly gurnards, Cape horse mackerel, spiny dogfish, shallow-water hake and white sea catfish.

A century of trawling may have altered seafloor habitats, indirectly contributing to changes in the fish community, Currie said.

UCT in global Mission Atlantic project

UCT’s Dr Lynne Shannon teamed up with global ocean experts from Europe, South and North America to map and assess the current and imminent environmental risks posed by climate change, natural disasters and human activities and their effects on Atlantic Ocean ecosystems.

The global Mission Atlantic project will also explore sustainable development of the Atlantic Ocean and is the first initiative of its kind to develop and systematically apply Integrated Ecosystem Assessments (IEAs) at the Atlantic basin scale.

Dr Shannon, of the Department of Biological Sciences in the Faculty of Science, is leading Mission Atlantic’s southern Benguela case study.

The €11.5 million initiative has been funded by one of the European Union’s (EU) Horizon 2020 programmes. Using the unique IEA approach, this study engages scientists, marine stakeholders and resource managers, and incorporates all components of the ecosystem, including human activities, into the decision-making process. By doing this, project managers and policymakers will be entirely informed by science and will be able to balance the need for environmental protection with secure, sustainable development.

Mission Atlantic uses high-resolution ocean models, artificial neural networks, risk assessment methods and advanced statistical approaches to accurately assess pressures imposed on the Atlantic marine ecosystems. It identifies the parts most at risk from natural hazards and the consequences of human activities.

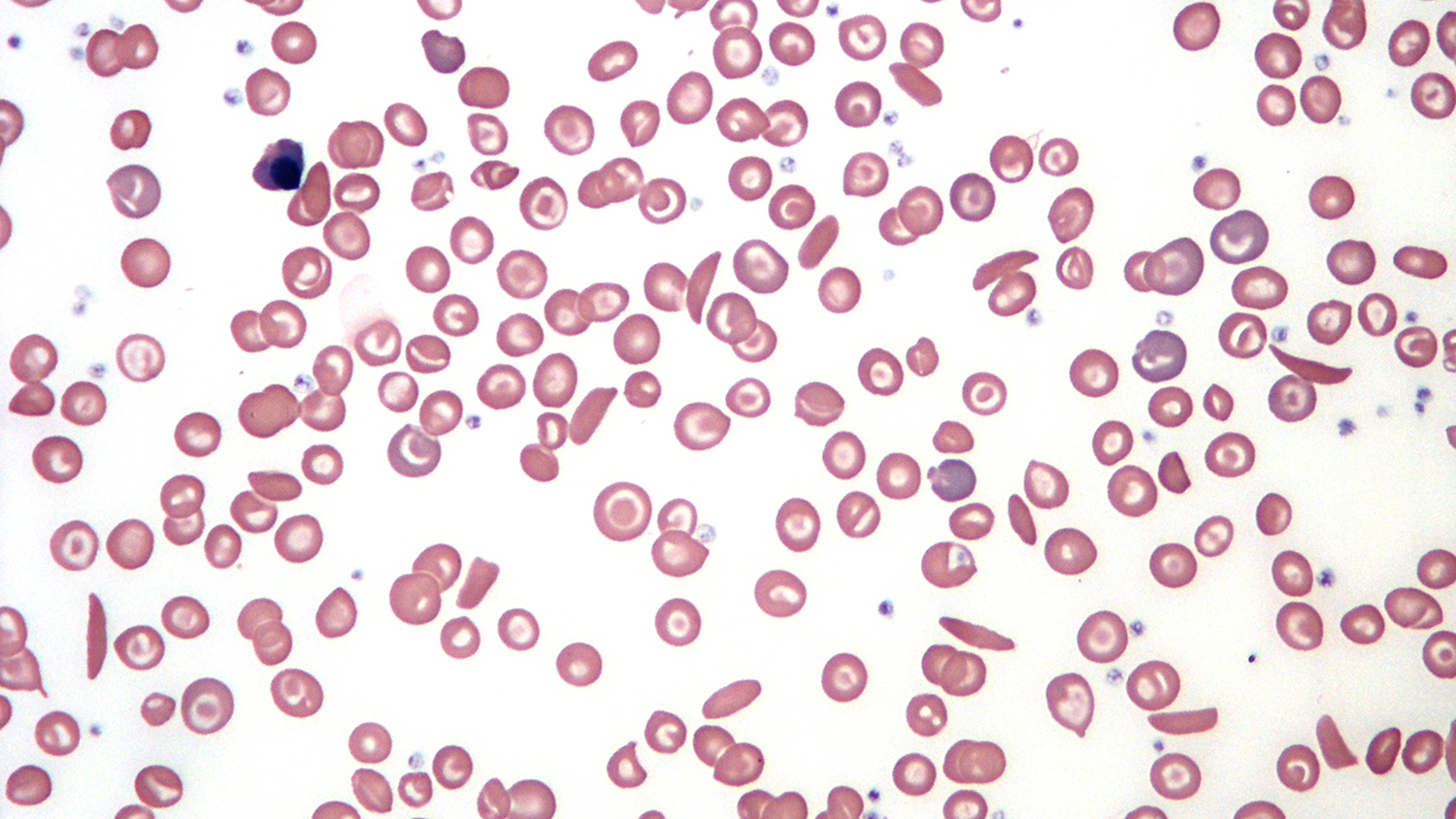

Sickle cell genetics study a first

Sickle cell anaemia (SCA) is deeply rooted in Africa but new UCT research, using next generation DNA sequencing, is investigating the genetic modifiers of long-term survival in individuals with SCA and revealing a range of possible pathways for novel therapeutic interventions.

Study leader and principal investigator Professor Ambroise Wonkam is the director of Genetic Medicine of African Populations (GeneMAP) in the Division of Human Genetics. Wonkam said that apart from the study’s clinical potential, the fact that SCA is so prevalent in Africa presented the opportunity for a paradigm shift in science policy and diplomacy.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is caused by a mutation in a single gene, which is responsible for production of the protein, haemoglobin. SCA is the most severe manifestation of SCD.

Despite the prevalence of SCA in sub-Saharan Africa, most of the critical research into the disease has been conducted outside Africa. With its cohort of 192 African SCA patients, recruited at African hospitals and conducted at an African university by African researchers, Wonkam’s genetic study is a first for the continent.

Because of poor clinical interventions, in most African settings at least 50% of children with SCA will die before they turn five. But regions of sub-Saharan Africa are also home to SCA patients who are 50 or 60 years old.

The genetic modifiers present in these individuals may hold the key to exploring new routes of treatment for other SCA patients.

“If we know how it works in their body,” said Wonkam, “we can provide new treatment looking at those pathways.”

When crisis cultivates collaboration

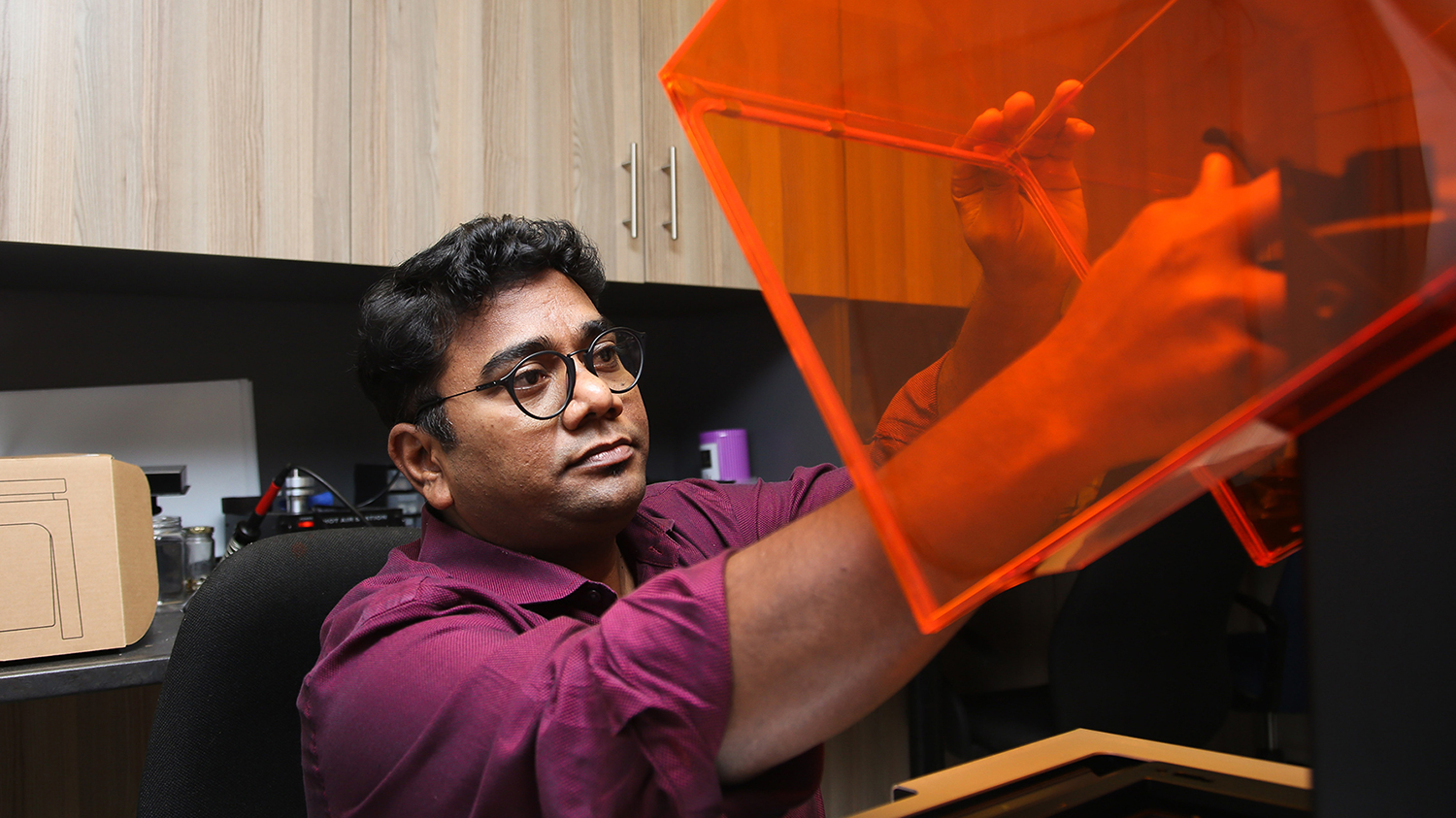

For Associate Professor Sudesh Sivarasu and his innovative team of biomedical engineers, COVID-19 brought an opportunity to serve the greater good through collaboration and sharing knowledge to create technologies appropriate to Africa’s context.

In response to the pandemic, Sivarasu and his team worked on a variety of biomedical devices, including a face shield, the UCT ViZAR, a simple but effective home-grown technology for tackling COVID-19 that can be made easily with household items.

The ViZAR was among the first of the team’s COVID-19 protective face shielding solutions to have been approved by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA). It acts as a first line of defence between the user and any infectious, airborne particles.

The ViZAR was designed by postgraduate researcher Matthew Trusler of the Division of Biomedical Engineering, in collaboration with Sivarasu and Dr Stephen Roche of the UCT Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, Professor Salome Maswime and Dr Tracey Adams of the UCT Division of Global Surgery, and Saberi Marais from UCT Research Contracts & Innovation.

But instead of going the 3D-printing manufacturing route, the UCT team opted for a hand-made approach, using easily accessible products. This allowed the team to scale their production to the order of a few 1 000 ViZARs a day, facilitating job creation through a sustainable and local supply chain.

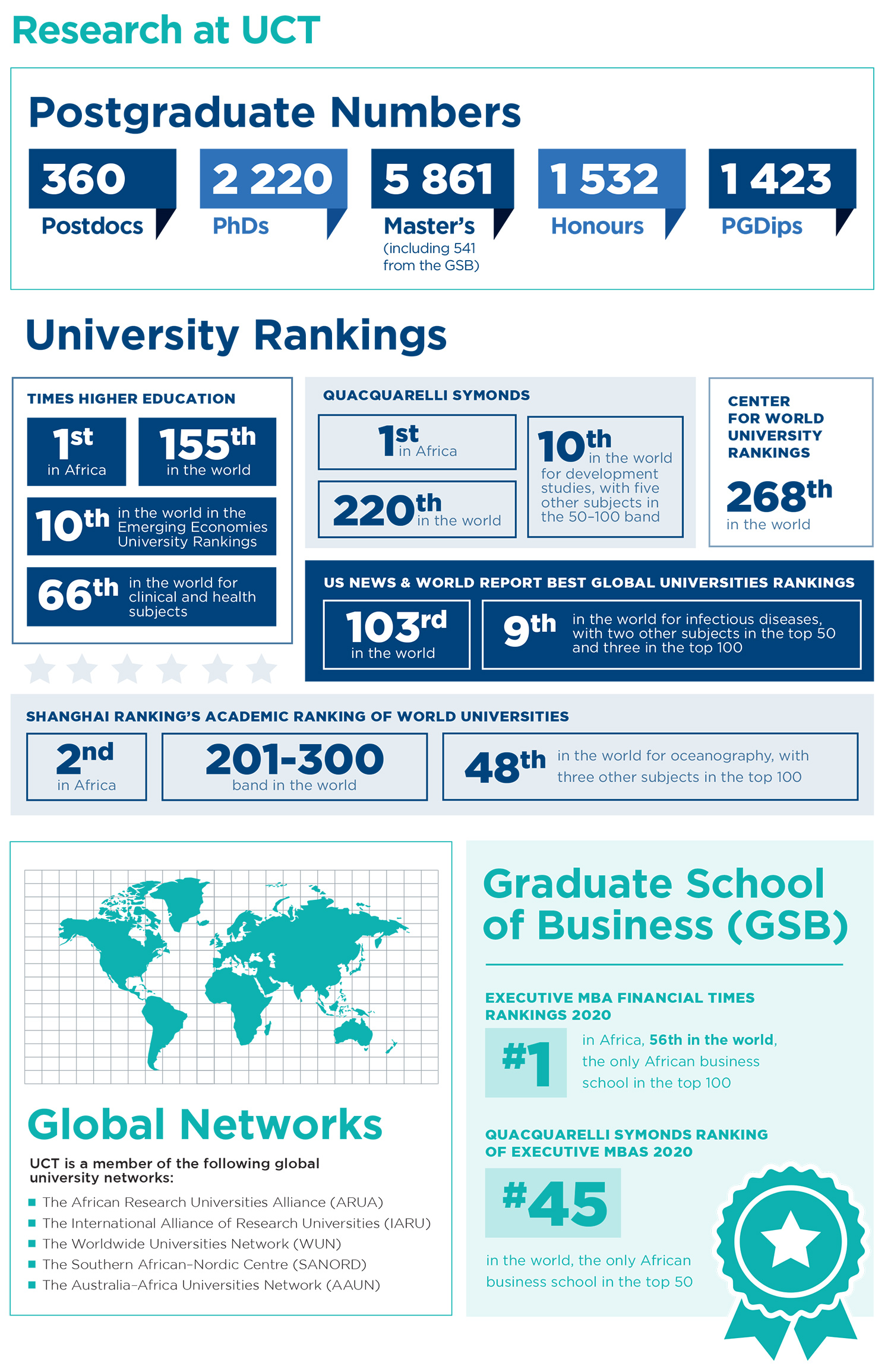

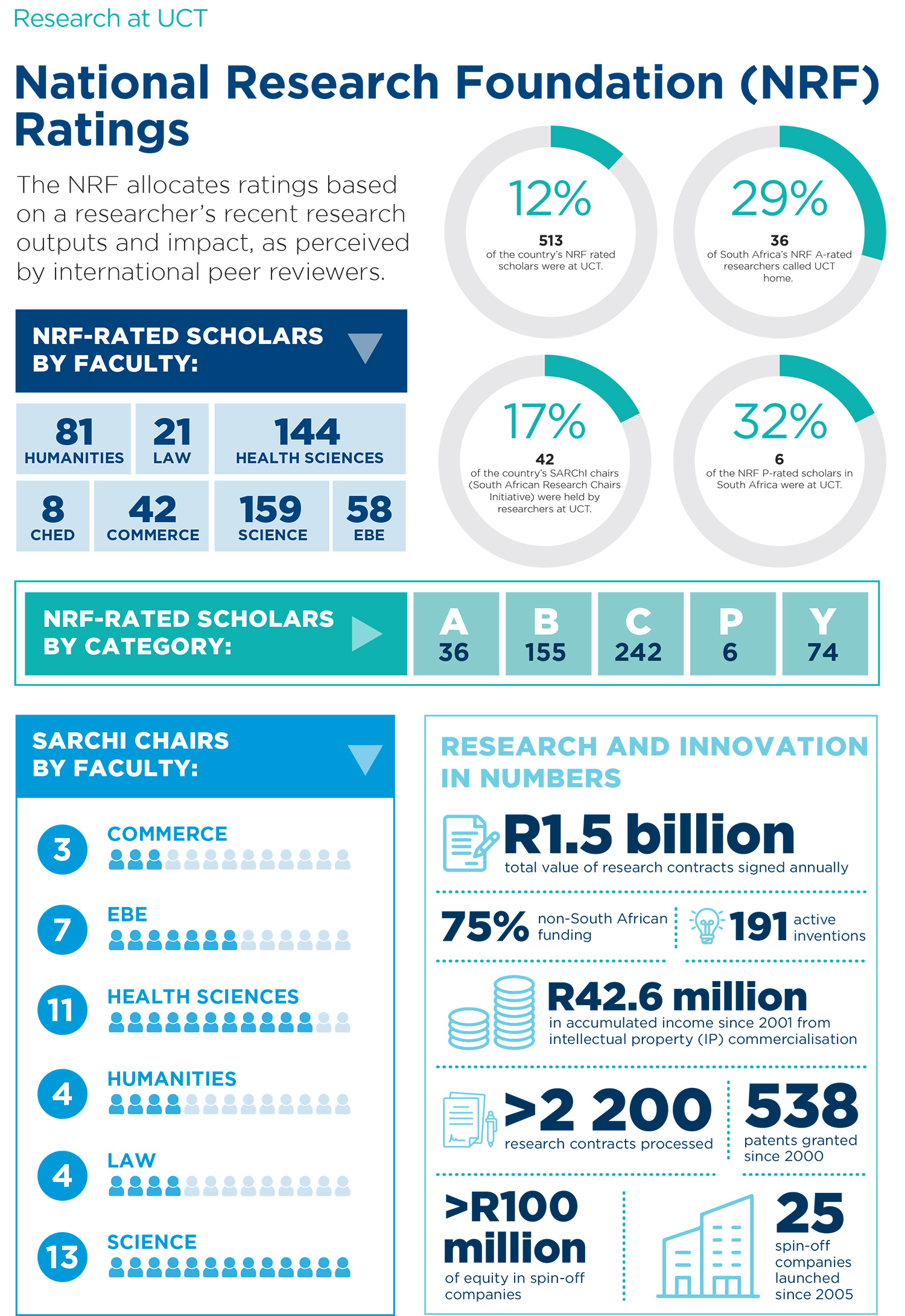

Research at UCT infographic

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.