The devastating condition that can cause cancer in children

27 May 2015 | Story by Newsroom

Doctoral candidate Lindiwe Lamola has had a grudge against cancer since it caused the death of her much-loved grandmother. She is channeling her energies into examining a rare genetic syndrome that puts people at risk of developing cancer in childhood.

In her dreams, health sciences postdoctoral student Lindiwe Lamola sees a four-year-old child playing, dressed in pink and with pigtails in her hair. But in her daily research job, Lamola knows this child only by her DNA case number.

"I often see her in my mind's eye, riding a bicycle; but she probably had headaches too bad to allow her to play like other children," says Lamola.

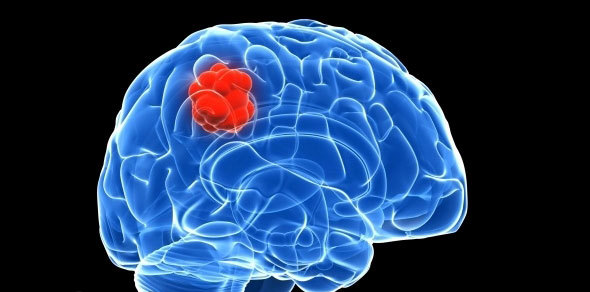

The child in question died from a rare genetic cancer syndrome, Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency (CMMR-D), which caused an aggressive tumour in the brain. She had inherited the genetic defect from both mother and father.

To date, fewer than 200 cases of this syndrome have been described worldwide, says Lamola. As with many cancer syndromes, it increases an individual's risk of developing early onset cancers, including brain tumours (as in this case) and gastrointestinal and haematological cancers.

"In my study, we aim to find the underlying genetic features involved in the initiation of cancers in patients with genetic defects in their DNA repair machinery.

"This study will add to the understanding of the disease and contribute to improving surveillance by determining biological markers, which may be used to monitor disease initiation and progression.

"We may not have been able to save this child, but maybe we can save others," says Lamola. "We understand so little about CCMR-D syndrome. We want to see if there is a better method of surveillance or to diagnose it earlier. For instance, are there any markers we can identify before it gets to that fatal stage? We're just starting with the basics, such as: what makes this disease?

"We have started with one family, and we hope we can find something and expand the study. The more we understand about the different types of cancers, the more we get to understand about cancer. It could be that something from this study will help us understand more about other cancers," says Lamola.

Her research stems from a bigger Division of Human Genetics study, which aims at investigating the genetics of inherited cancers in South Africa.

The Division of Human Genetics and the Surgical Gastroenterology Unit at Groote Schuur Hospital initiated the parent project to investigate the molecular basis of hereditary colorectal cancers in local populations. As a result of this project, the genetic determinants of Lynch syndrome in different families in South Africa have been described. "Lynch syndrome is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder (a disorder in which each affected person usually has one affected parent, and the chance a child will inherit the mutated gene is 50 percent), and is associated with the early onset of colorectal cancer," says Lamola.

"It's caused by a defect in one of the four mismatch-repair genes – when patients are diagnosed with this, they have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.

"Because of the burden of cancer – particularly colorectal cancer – in our population (it has grown exponentially in South Africa over the past few decades), methods were put in place for creating a registry and surveillance programme. Currently, communities are being managed pre-symptomatically via genetic testing, genetic counselling, and colonoscopies. We have shown what a difference a surveillance programme can make in this population."

It was from that newly-created registry that the study into CMMR-D syndrome was initiated (Lamola's supervisor for the study is Professor Raj Ramesar, head of the Division of Human Genetics and director of the UCT/Medical Research Council Human Genetics Research Unit).

"There was a case of a four-year-old child who had fallen ill and died, due to a brain tumour," says Lamola. The victim was the child of parents who are not related to each other but who both had a Lynch-syndrome genetic defect in their respective families – and so both parents had the defect present. "As with the other family cases with such a genetic defect in our registry, this family was tested and later included in the surveillance programme – the parents and the child.

"This particular cancer syndrome is so aggressive, and takes lives so fast; and unlike colon cancer, it hits people much younger, from ages two to 15. It is extremely rare; but if we knew more about it, we could at least arrest it – give more years to victims' lives.

Lindiwe Lamola.

Lindiwe Lamola.

Lamola's grandmother, Elizabeth Lamola, died of cancer when she was 14. "She practically raised me. She was only in her 60s. We were very close to my mother's parents growing up in Qwa Qwa, in rural Free State.

"I've had a grudge against cancer ever since. I'm not looking for a cure; I just want to understand: who are you, cancer – why do you think you have the right to take a life? Why do you do what you do?

"My gran was normal one day, and the next she had a cough. They discovered inflammation in the lungs, and then diagnosed lung cancer. Just like that, this tough, resilient woman became someone who couldn't even get out of bed. This woman who had raised me, who was normally out of bed at the crack of dawn ... in a few months, she was unable to talk, to walk. Everything I had identified her by, she was none of that anymore. Hence my grudge against cancer."

When Lamola was growing up, at first she wanted to become a doctor. "I could see the need in the rural area I grew up in; but then I decided rather to work on things that could show doctors what caused disease. My grandparents and parents always instilled in me that education is important. You have to work really hard to get to this point. I'm the first one in my family to stay in the field of academia.

"I always say that to be in academia, it has to be about the love of what you're doing, not about the money. In my case, it's the love of science ... and for now, the possibility that I can come to understand cancer better – that the world can; and that it will no longer be the devastating disease that it is now."

Story by Vivian Warby. Image of Lindiwe Lamola by Michael Hammond. Image of brain scan with tumour from Online Cancer Guide.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.