The UCT art collection: past and present

22 October 2025 | Story Justin Keep. Photos Justin Keep. Read time 10 min.

From the sculptures you see as you eat your lunch to the photographs you rush past to get to a tutorial – there’s a lot more to each piece of art around the University of Cape Town (UCT) campus than just aesthetics.

The office of Nadja Daehnke, curator and collections manager of UCT’s Works of Art Collection (WOAC), is a busy place. Dozens of frames, sculptures and files in neat stacks surround her desk, all labelled with eventual destinations across campus. Were you to ask Daehnke how she goes about managing the university’s art collection, the busyness would begin to make sense.

Troubled beginnings

UCT has, as Daehnke put it, “quite an old-fashioned art collection”, which started from a number of donations in the 1920s and 30s. Despite its colonial roots, the collection now consists of over 1 800 pieces of diverse mediums and artists – from Africa and beyond. Acquired by way of donations, commissions, and purchasing at full price, it includes everything from paintings to recordings of ceremonies.

Daehnke said that this diversity is relatively new: “In 2016/17 [amidst the RhodesMustFall movement] there was a hiatus period where the WOAC committee [standing since 1978] was disbanded and, instead of a Works of Art committee, they [students and the university] established an Artworks Task Team.” This task team audited the collection and found it to be “predominantly white artists [79.1% of all works] and also dominated by male artists” So, this team set out to reorganise and revitalise UCT’s art collection, with one question: What is the way forward?

The way forward

The answer, Daehnke said, is still central to the curatorial policy of the reformed WOAC committee: representation. Yet this representation isn’t merely a tick-box exercise; it’s about finding the curatorial gaps in the collection. “We as a committee look at the collection and go, ‘Well, what’s missing? What is over-represented? What is under-represented? What do we need? How do we tell a better story of what we have by adding something?’”

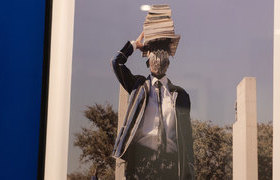

Luckily, WOAC doesn’t have to ask or answer these questions alone. Daehnke explained: “Very often it’s prompted by discussion and engagements with students and staff, and also engagements with people from the art world.” Most recently, an emphasis on including more queer artistry in the collection came after staff and students brought this curatorial gap to WOAC’s attention. Discussions like these saw pieces like Haneem Christian’s “The Memorial Ball” photo set installed across campus. Now adorning Beattie Building, these images commemorate the life and tragic death of one of Cape Town’s prominent drag mothers.

Today’s challenges

Although WOAC’s goal is change, it has its limits. “It’s not easy, because often you see work, and you just can’t afford it, and you wish you had it! Funding is a huge issue for us,” she explained. Since 2016, most WOAC acquisitions have been full-price purchases or commissions. It’s a financially tough but necessary choice given how donations can undo a lot of the committee’s hard work: “There were a lot of donations by people who very kindly gave their work but often gave multiples of a work which then skewed the collection again.” As a result, Daehnke said, donations are “fantastic, but have to be looked at carefully”.

So, next time you find yourself chewing your lunch beneath a statue or rushing past a painting, think of how it got there. The marks of reform, a student revolution and the keen eyes and considerations of dozens are found across campus in these artworks. As Daehnke would say: it’s all to “make sure that every person who looks at the collection has something where they feel seen and heard”.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.