When a moment becomes a movement

02 July 2020 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Flickr. Voice Lerato Molale. Read time 10 min.

The power of social media to turn a moment into a movement has been starkly evident in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder by police in the United States (US), which reignited Black Lives Matter protests across the globe. But questions remain about who holds the power of media and its ability to shape important narratives of our time.

This was the topic of a 26 June University of Cape Town (UCT) webinar titled “I can’t breathe: The role of social media and journalism in social justice protests”* with civic activist and founder of amandla.mobi, Koketso Moeti, and Maxwell Maseko, news assignment editor at the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC). The webinar was a collaboration between UCT’s Centre for Film and Media Studies and the Centre for Extra-Mural Studies.

Against the backdrop of COVID-19 and its spotlight on global racial and economic inequity, media scholars and practitioners have been asked to reflect on the role of social media and journalism in creating a more equitable future – and a voice for the most marginalised.

In South Africa, Floyd’s death highlighted the disquietingly lacklustre response to Collins Khosa’s murder in Alexandra on 10 April by military personnel enforcing lockdown. It initiated crucial conversations about the collective role of responsibility in highlighting these incidents, the role of racism in society, and the power of media in shaping and presenting news.

That social media can effect change was persuasively presented in the parody of Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda”, which called out Unilever for exposing residents of Kodaikanal, India, to mercury contamination. Years after the event, the consumer giant was forced to act.

“It became a global phenomenon, well beyond the borders of India,” said Moeti. “It’s an example of how the digital realm mobilises, gets information out and connects others. A story became a springboard to connect people to the workers’ struggle. It was more than a moment – it became a movement.”

Technology and connection

But social media is not new in connecting people and creating networks. Technology has always been at the frontlines of change and people have always used it in their artillery, she said. That long legacy of mobilisation – from print to fax to Google Docs – has kept people informed and connected across space and time.

“The power wielding technology matters too – in the way it’s used, who owns it and who distributes it.”

Technology is not the whole answer, Moeti said. The power wielding technology matters too – in the way it’s used, who owns it and who distributes it, “as seen with Cambridge Analytica and as we’ve seen with the rise of surveillance and other abuses”.

However, if used strategically, it can be a springboard for action across many fronts. During the Fees Must Fall protests, arrested activists used social media to call for toiletries, medical care and bail money.

“They were able to reach out to those not physically present at the site but able to help [the struggle] in other material ways.”

Though storytelling and journalism were critical tools in the cause of social justice, social media’s immediacy opened multiple ways for people to participate.

“The public can mobilise only based on what they know.”

Who tells the stories?

The power behind the media also influences who tell the stories. Moeti said that after Marikana, most media interviews were with the police and mine officials rather than the mine workers themselves. These omissions of key voices diminished the potential for change at a structural level.

“So, from whose perspective are stories being told … from whose perspective is it being reported?”

COVID-19 had presented other challenges for newsrooms, Maseko said.

“We need to report on COVID-19 for the safety of all communities – and we have to be safe ourselves as we go out and cover these stories.”

“Our challenge is to ensure that the public trusts our products and we report accurately and ethically.”

The SABC’s broad mandate to serve an entire country also stretches resources. Their editorial policy serves as their bible.

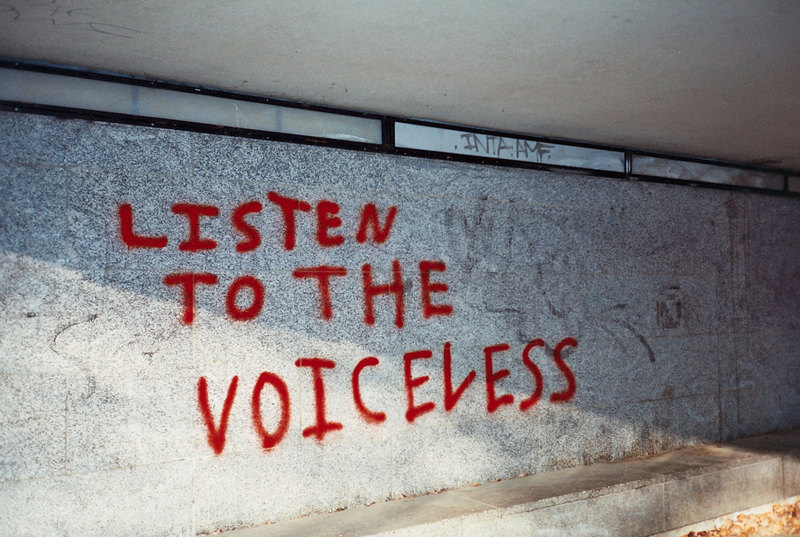

“With the world today and all its problems – femicide, inequality, social justice – we as newsrooms acknowledge that we are challenged. Newsrooms are downsizing staff and resources, yet we are expected to be at the fault lines of issues, hold authority to account and be the voice of the voiceless in the communities. How do we manage the bigger crises? Our challenge is to ensure that the public trusts our products and we report accurately and ethically.”

As a public broadcaster, the SABC also reports in more than one language.

“How do we ensure the message is the same across all the channels and that there’s no distortion?”

Violence backlash

While social media gave the voiceless a voice, held people accountable and exposed wrongs in real time, it created public figures of those who recorded the pictures and footage, with dangerous consequences. After 17-year-old Darnella Frazier filmed Floyd’s murder, she became the target of a violent backlash.

Moeti added, “We’d love to believe these spaces are democratising … but that’s not the reality – whether we’re talking about surveillance capacity or about harassment and the retaliation women face online and offline.”

Society has an obligation to support those at risk, those telling the stories and “show up” for them. Those at the frontlines should learn how to film abuses safely, knowing when and how to blur or remove the faces of those being abused – and how to safely release images and video.

Responding to a participant asking whether social media shed more light on injustices than TV and other media, Maseko said, “I’m inclined to say yes. A lot of what we see today in communities comes from social media. What’s important is what we do with that social information. Do we trust what comes from social media or do we do our own homework?

“Social media has played a very important role in bringing out some of the injustices … and just because we can’t be everywhere at the same time, it allows us to reach the most obscure communities out there. We can be a voice for those communities.”

Moeti warned about the dangers of sidelining smaller provinces and towns as the media concentrates on the larger metros.

“There’s so much going unseen in this country, and globally, as the media houses shrink.”

“There’s so much going unseen in this country, and globally, as the media houses shrink.”

Other inequities replicate themselves in these spaces.

“Who has access to data? What kind of device are you using?”

English literacy was also a barrier to internet usage.

“A lot of what’s available is in English, a minority language in this country.”

There is also the human bias behind search engine algorithms, creating an internet power structure, with companies such as Facebook and Google owned by those “with power and intergenerational privilege”.

The collusion of state and capitalism also drives specific narratives through traditional media channels.

Their editorial policy review is aimed at limiting interference in their work, said Maseko.

“Whose questions were privileged over whose? Whose convenience was being privileged? Who matters?”

Trivialising a crisis

Turning to COVID-19 coverage, Moeti said that important debates on inequality had been lost.

“So many crises came on top of this [pandemic] in this period. I knew so much about the tobacco ban, the surfers protesting, the Woolies [rotisserie] chicken, that I was like, is there damn well nothing else happening in this country? Whose questions were privileged over whose? Whose convenience was being privileged? Who matters?”

These incidents could have been used to highlight the “disconnect”.

“The Woolies chicken issue could have been taken deeper; what about ready-made meals for those working at the frontlines, for essential workers who didn’t have time to cook? They missed a springboard to so many issues. And dogs not being walked. I would have been more interested to know what lockdown means to someone who lives in a densely populated area and can’t go outside.”

While there has been some “pockets of really great reporting”, Moeti said the power struggle was evident in those dominant narratives.

On the dilemma facing news editors, Maseko said, “On a daily basis we juggle with what makes news. There’s a realisation that we can’t cover everything and be everywhere. We try as much as possible to involve everybody. It hasn’t been an easy process, but we strive to be as inclusive as possible.”

*The webinar was meant to have included Patrice Peck from the US, but she was unable to participate.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.