Residence renamed after education activist Harold Cressy

05 October 2017 | Story Helen Swingler, Michael Morris.

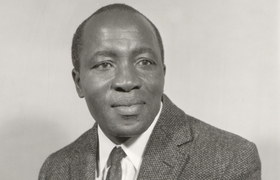

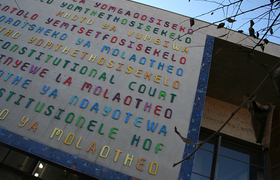

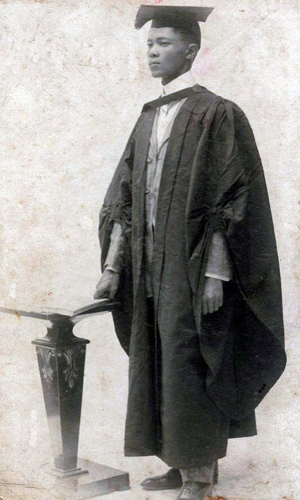

UCT has renamed the Palm Court student residence in Mowbray after education activist Harold Cressy, the country’s first graduate of colour who qualified at the South African College, UCT’s forerunner, in 1910. The residence, a third-tier co-ed facility that is home to 58 senior and postgraduate students, is now known as Harold Cressy Hall.

The renaming event on 3 October was attended by the Cressy family and friends, as well as alumni and staff of the school that bears his name: Harold Cressy High School in District Six (formerly Cape Town Secondary School and renamed in 1953), a provincial heritage site since 2014.

Though he died young at 27, Cressy’s legacy has remained vivid and inspiring, writes journalist Michael Morris. A century after his death, he remains a symbol of the power of education in challenging bigotry and nullifying its effects.

Early years

Cressy was born on 1 February 1889 at the Rorke’s Drift mission station in KwaZulu-Natal. At age eight, his parents, Bernard and Mary Cressy, sent him to Cape Town where he was enrolled at Zonnebloem College.

He qualified as a teacher at Zonnebloem in 1905 and, a year later, at the improbable age of 17, took up his first post at the Dutch Reformed Church mission school in Clanwilliam.

Determined to extend his own learning, he continued his studies, gaining the matriculation certificate that would be the springboard to the university education he sought. His race, however, proved to be an impediment.

Though his academic excellence earned him a study bursary from the Department of Education, his application to enrol at Rhodes University College in Grahamstown was unsuccessful – the university turned him down when it discovered he was a “coloured” man.

Cressy then applied to Victoria College, the forerunner of Stellenbosch University, but was rejected on the same grounds.

Key partner

Undeterred, he applied to the South African College, later UCT, and succeeded – though not without the influence of Dr Abdullah Abdurahman, a man who would become a key partner in Cressy’s larger educational vision.

Abdurahman was a Cape Town city councillor and president of the African Political Organisation (APO), to which the young Cressy was drawn after his graduation from UCT.

Having secured a teaching post at St Phillip’s Primary School in District Six, Cressy used his free time to contribute to APO activities in Cape Town in addressing the condition of people subjected to the mounting social injustices of the time.

His primary interest, however, was improving the quality of coloured education.

Building blocks

Cressy’s scope to do so was considerably enhanced with his appointment in 1912 – the year in which he married Caroline Hartog – as the principal of District Six’s newly established Trafalgar Second Class Public School, the first in South Africa to offer secondary-level (Dutch, Latin and elementary science) education to pupils of colour. He was just 22.

Within a year, Cressy had announced the graduation of the first pupil of colour in the country in the University Junior Certificate Examination, then called the ‘School Higher’. The result was additionally meaningful – the successful candidate was Rosie Waradea Abdurahman, the eldest daughter of his political mentor.

In 1913 their collaboration led to the establishment of the Teachers’ League of South Africa (TLSA), at whose inaugural conference Cressy was elected president.

The TLSA became a critical vehicle of resistance under apartheid. It was also the wellspring of a tradition of non-racialism that informed generations of teachers and students whose non-collaborationist convictions helped undermine the ideology of race.

Education challenges

The challenge for the TLSA is eloquently expressed in the comment in the APO newspaper of August 1911 that “(t)he results of investigations have shown that thus far the School Board Act has conferred no benefit on the Coloured population”.

Pressure brought to bear on the Cape School Board had, at least, led to the founding of Trafalgar, but Cressy had no illusions about the need for more concerted action if further advances were to be achieved – the dominant theme of succeeding issues of the TLSA’s Educational Journal, and the defining motif of the organisation itself in the decades that followed.

Cressy is acknowledged as having resisted the co-option to which more moderate colleagues were prone. In a 1947 tribute, Dr GH Gool wrote in the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM) newspaper, The Torch, that while the government had turned to teachers “to pick its group of Quislings … Mr Cressy had opposed the anaemic stand of the teachers who formed the old TLSA, (though was) unfortunately ... alone in his attempt to oppose injustice consistently, and he could not carry the old encrusted Guard with him”.

That changed from the 1940s when the TLSA invested its motto, “Let us live for our children”, with a fiercer resolve.

The motto had been adopted in 1918 and, though Cressy had already died (two years earlier of pneumonia in Kimberley), it captured the remarkable teacher’s own lodestar.

He had written, only months after his graduation in 1911, of the capacity of education to provide “happiness in the highest and best sense”.

Process of transformation

In his welcome address at the Harold Cressy Hall renaming ceremony, Registrar Royston Pillay said that Cressy’s name had become iconic in Cape Town, linked to District Six and later to the Harold Cressy High School. The school’s record of academic excellence through the decades was informed by Cressy’s fortitude and by his values − and his capacity to envision the future.

That future was bound to the legacies and injustices of colonialism and apartheid, as the recent student protests have reminded the country.

Renaming buildings, facilities and roads at the university is part of a continuing, multifaceted process of transformation to overcome this legacy, and to make UCT a home to all, Vice-Chancellor Dr Max Price said in his address at the function.

The 2015 protests under the Rhodes Must Fall banner had added urgency to the process. Among other transformation initiatives, the Task Team on the Naming of Buildings, Rooms, Spaces and Roads was created in 2015 to effect faster change to the physical campus.

“Renaming decisions are not neutral acts,” said Pillay. “They represent the markers of how an institution is grappling with who we are, where we have come from, and where we are headed. They represent an institution in deep and ongoing and necessary discussion with itself … it’s a sign of doing what is necessary and responsible.”

“Renaming decisions are not neutral acts. They represent the markers of how an institution is grappling with who we are, where we have come from, and where we are headed.”

Addressing the gathering in Harold Cressy Hall, Students’ Representative Council Secretary-General Sinawo Thambo said he’d been inspired after reading about Cressy’s life. He also thanked the family for the sacrifice made by Cressy and his dedication to emancipation and black excellence.

He paid tribute to the student activists and UCT workers for their role in transforming the institution.

To the Cressy family he said, “Thank you for giving us, and blessing us, with the name that can be used for this hall.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.