Dinosaur bones debunk migratory myth

04 April 2012 | Story by NewsroomOnce dubbed the 'happy wanderers' of the North Pole, a new study suggests that duck-billed dinosaurs weren't migratory at all. They preferred to stay closer to home, it appears - the evidence, as a UCT and American team has found, is in their bones.

|

|

| The bones don't lie: Prof Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan and Dr Daniel Thomas collaborated on a project that investigated the bone structure of the Alaskan polar dinosaur. | A long, long time ago: The bones of duck-billed dinosaurs that lived at higher latitudes of the Arctic revealed a winter and summer growth pattern, unlike the bone structure of similar dinosaurs found at lower altitudes. |

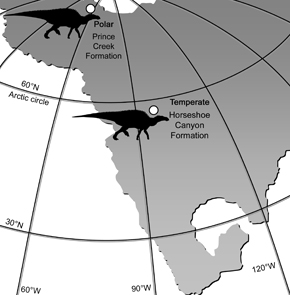

A team of dinosaur palaeontologists from South Africa and the US have uncovered these insights in the bones of Edmontosaurus, or duck-billed dinosaurs, which lived in the Arctic about 70 million years ago.

Bone histologist and head of UCT's Department of Zoology, Professor Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, and colleague Dr Anthony Fiorillo, of the Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas, Texas, reasoned that perhaps clues showing how these dinosaurs lived at such high latitudes might be recorded in the microscopic structure of their bones. With this in mind, the team - which included postdoctoral researcher Dr Daniel Thomas, then at UCT, and Dr Allison Tumarkin-Deratzian of Temple University in Philadelphia, US - began a study of the microscopic structure of the bones of the Edmontosaurus, aka the Alaskan polar dinosaur.

The bones, the researchers found, had an odd structure. Similar to tree rings, they showed periodic changes in texture, suggesting a summer and winter bone deposit pattern - most likely related to the availability of food.

"Since there would not have been green foliage [during the polar night], they probably fed on alternative food such as underground tubers," Chinsamy-Turan says.

In one of the largest individuals (approximately 65% of adult size), at least eight cycles of faster bone deposition were counted, suggesting that this individual lived through eight summers. Bones of Edmontosaurus that lived at lower latitudes (in Southern Alberta, Canada) did not have the regular, alternating bone pattern, implying that these duck-billed dinosaurs were spared the stress of long, dark winters.

The unique pattern of bone deposition in the polar dinosaurs also suggests that they overwintered well within the Cretaceous Arctic circle. So out go the assumptions of nomadic dinosaurs.

But another question has cropped up after the researchers found bones mainly belonging to younger animals.

The fact that many of them seem to have died at the beginning of spring, and that their fossilised bones are found in melt deposits, have led researchers to believe that seasonal flooding may have led to their death, says Chinsamy-Turan.

"Perhaps the adults were better able to cope with seasonal flooding than the young."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.