The value of storm water

14 May 2018 | Story Kevin Winter. Photos Kevin Winter. Read time 5 min.

The proposed Cape Town water tariff for 2018/19 ignores storm water as a water augmentation opportunity, even though it could be critical in bolstering the city’s scarce water supply and its resilience to climate change, says Dr Kevin Winter of UCT’s Future Water Institute.

“Social media on water matters lights up every time it rains over Cape Town,” says Winter. “Citizens report on how the latest rainfall has filled their water tanks and how they are using this water in their homes. Cape Town’s water crisis appears to have changed the level of interest in water resources for the good.

“There is no shortage of ideas of what to do to address the water crisis. Moreover, citizens are adhering to a relatively stable water demand even though the set target of 450 million litres per day appears to be a stretch too far.”

Many households have adapted to the restrictions and now look to other ways in which water can be conserved.

Watching water going to waste

Storm-water harvesting seems an obvious opportunity for capturing water that is lost to the sea. It involves collecting, treating, storing and reusing water, but like any large scale water project, it comes with some challenges.

“We don’t know the volume or quality of the storm water,” he says. “We appear to lack some creativity in storing storm water and in using it to recharge the aquifers.

“The proposed City water tariff for 2018/19 also ignores storm water as a water augmentation opportunity because it is skewed toward finding new water supplies along with the importance of maintaining and operating existing water-based services. However, storm water could be critical in bolstering Cape Town’s scarce water supply and resilience in dealing with climate change.

“It starts with new thinking: the city is a catchment. If this idea is going to take hold, then we need to know a few things about storm water. The problem is that we have so little data about storm water across the city.”

“We appear to lack some creativity in storing storm water and in using it to recharge the aquifers.”

New technologies to monitor flow

Over the past two years scientists and engineers at UCT’s Future Water Institute have been developing and testing logger devices that are capable of capturing real-time data about the flow and volume of water.

A recent example illustrates how a large volume of water could be captured, stored and used to recharge aquifers.

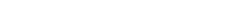

On 23 April 2018, the headwaters of the Liesbeek River received rainfall of 34 millimetres as measured at Kirstenbosch. Data loggers at a number of locations along the river recorded the rise in water levels at five-minute intervals and were able to transfer this data via a network to a computer server.

Figure 1 below shows how water levels rose dramatically after 16:20 until it reached peak volume at 17:20. Over 24 hours more than 500 million litres of water was discharged under the Durban Road bridge at Mowbray.

Says Winter: “The volume is substantial but it won’t be easy to capture this water. River corridors are built up and have few opportunities for capturing and storing water especially when it is flowing fast and furiously down a small river corridor.”

Opportunities to capture storm water

In 2014 the Friends of the Liesbeek and UCT’s Urban Water Management group arranged for the City of Cape Town to excavate a small channel to connect the river with a floodplain alongside. The floodplain had been separated from the river for some time by a tall bank. What happened next is simple – and remarkable in its simplicity.

When the Liesbeek reaches peak flow, water flows naturally through the channel and converts the floodplain into an active wetland. It helps to recharge the groundwater and the aquifer, and potentially reduces the flood risk further downstream.

Valuing storm water

Storm water is being ignored as a water resource possibly because too little is known about its behaviour and risks to health and potential to flood areas, says Winter. Managing the risk starts by measuring and monitoring flow.

“The technologies are making it easier to determine what is possible, but there has to be a new determination to use storm water as a means of recharging groundwater. It may not be possible to rely on rainfall alone to recharge the aquifers, yet storm water is missing from the City’s budget.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Cape Town water crisis

At UCT our researchers have been analysing the causes of the current drought, monitoring water usage on campus and in the city, and looking for ways to save water while there is still time. As part of UCT’s water-saving campaign, all members of the campus community are encouraged to reduce their water use by half, which will help Cape Town to meet its water-use goals and ensure a water-sustainable university in the future.