UCT helps unveil hidden pre-colonial cities with LiDAR

28 November 2025 | Story Lisa Templeton.Photo Supplied. Read time 7 min.

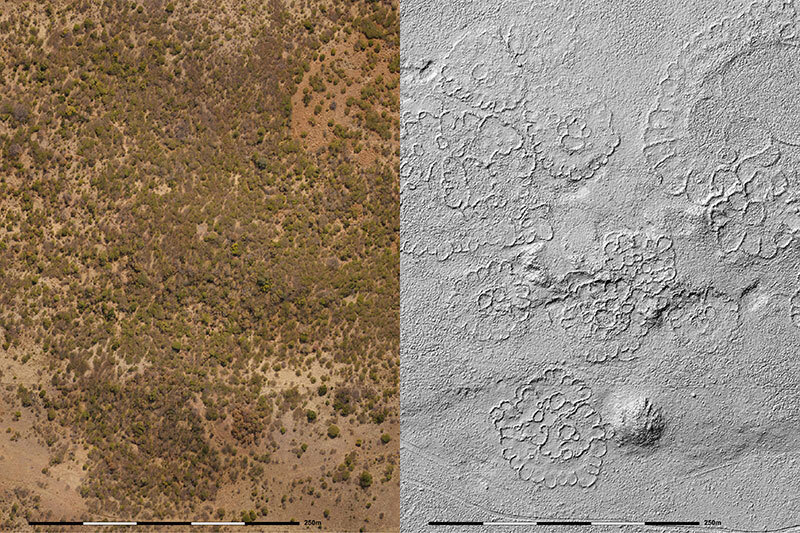

On screen, a stark black and white landscape appears cratered, almost lunar. But these are not celestial features: they are astonishingly clear images of the archaeological remains of a once thriving community. Homesteads, cattle kraals and the scalloped, semi-circular back courtyards of household after household emerge in remarkable 5 cm resolution.

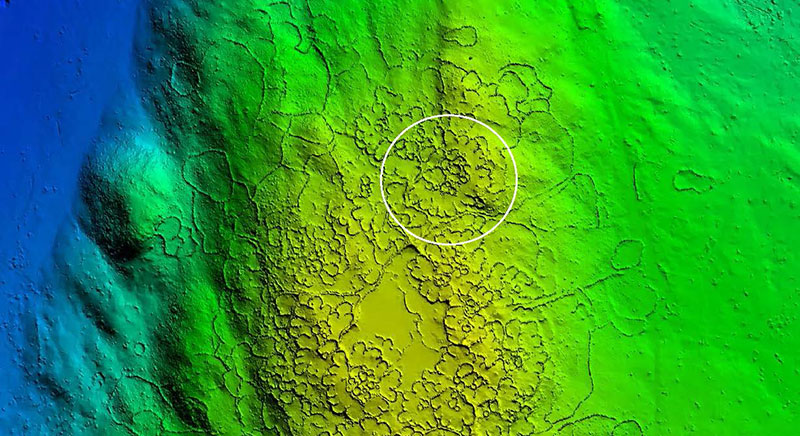

This early dataset, produced by a new Light Detecting and Ranging (LiDAR) project, captures only a fraction of the vast Iron Age stone-walled towns and villages established by Basotho and Batswana communities between 1770 and 1830, north-east of present-day Johannesburg.

A multidisciplinary team spanning the University of Cape Town (UCT), the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) and Global Digital Heritage Afrika (GDHA) is behind this cutting-edge LiDAR mapping initiative, which is transforming how archaeologists understand pre-colonial settlement patterns in South Africa.

LiDAR’s breakthrough lies in its ability to “see through” vegetation and map built structures at scale. Using laser light points and GPS receivers mounted on drones, planes or satellites, the technology generates high-resolution 3D data that reveals sites long hidden by dense bush or inaccessible terrain.

Although this archeological landscape has been documented and researched since the 1960s, the sheer scope made it impossible to map comprehensively – until now. The capacity to visualise tens of thousands of households across thousands of settlements could reshape understanding of pre-colonial South African urbanisation. These communities spanned what is today North West province, Gauteng, northern Free State, Limpopo and Mpumalanga.

Archaeological breakthrough

Arguably one of the biggest breakthroughs in archaeology since radio-carbon dating, LiDAR has been brought to South Africa by United States (US) non-profit organisation GDH, created by brothers who found success in Silicon Valley. GDH’s Africa chapter, GDHA, resides within UCT’s Department of Civil Engineering.

“GDHA has brought a spirit of innovation and collaboration that is truly admirable. Together, we are not just looking at maps; we are writing a new chapter in the story of our heritage,” said Advocate Lungisa Malgas, chief executive officer of SAHRA, at the project launch at the Castle of Good Hope. The initiative draws together GDHA, UCT and SAHRA teams, students, Heritage Conservation Management and others. Within UCT, the project spans the Faculty of Engineering & the Built Environment, the Department of Archaeology and the Faculty of Science.

“Together … we are writing a new chapter in the story of our heritage.”

“The sites we are surveying, Mmakgame, Kaditshwene, Molokwane and others, are the sacred footprints of our ancestors,” Advocate Malgas said.

Viewed on Google Earth, the Marathodi landscape reveals little beyond rocks and vegetation. Only brighter green patches hint at former communities, fertilising the soil with ash and centuries of human and cattle activity.

These were the features that first caught the attention of Dr Herbert Maschner, president and chief scientist of GDH, which is dedicated to democratising access to this extraordinary, costly technology for use in heritage sites.

GDH is investing US$10 million over the next five years to expand LiDAR access for heritage education and research, including data-sharing with descendant communities. The organisation has also used the technology at global heritage sites such as Petra in Jordan and the tunnels beneath the pyramids of Guatemala.

Unprecedented insights

Maschner recalled the moment he first saw the LiDAR images: “I was blown away.”

UCT’s Emeritus Associate Professor Simon Hall, who has spent many years excavating these sites, shared the sentiment. The new data, said the former head of the Department of Archaeology, allows unprecedented insight into settlement organisation, power structures centred on cattle economies, and extensive metal-working traditions supported by the region’s rich ore deposits.

“This incredible technology allows those of us who are working on these ancestral Batswana towns to see the spatial organisation in phenomenal detail,” he explained. “We can now identify features and complex social patterns in ways we could not previously.”

Associate Professor Amanda Esterhuyzen, also of UCT’s Department of Archaeology, said the images hold major potential for reshaping history education. “These images and the insights they generate should be printed large in our textbooks to provide a fresh understanding of the history of the last 500 years,” she said.

LiDAR offers a rare opportunity to map the full extent of settlement networks, only excluding areas overtaken by modern development. It also helps protect heritage threatened by mining, agriculture and urban expansion.

“What we are discovering is not only the presence of cities, but of huge farming communities,” said Maschner. “Archaeologists have known where people were settled, but have been unable to take such a massive view. Now we are able to see not only detail, but its vast scale.”

Emeritus Associate Professor Hall added that LiDAR finally offers a semi-quantitative way to estimate population size, which has long been a challenge in African archaeology.

Complex economic, political dynamics

These Batswana Iron Age communities centralised politically from the 1770s, partly in response to the expanding Cape colonial frontier. They flourished through trading, raising cattle and farming food crops, using sustainable strategies to support large communities and mitigate climate risk.

Oral histories, combined with the new imaging, reveal complex economic and political dynamics between chiefdoms prior to the disruptions of the Mfecane in the early 1800s. After the 1830s, following conflict, missionary expansion and the arrival of the Boer trekkers, Batswana autonomy was significantly eroded.

To date, 26 km² of this region have been captured by LiDAR.

“This collaboration between SAHRA and GDHA marks more than just a technological milestone. This is an African story that resonates across the world, and it will be told by people from the Global South,” said Professor Siddique Motala, GDHA’s scientific director and associate professor in UCT’s Department of Civil Engineering. Here, GDHA also houses one of the more powerful computers on campus.

Motala thanked Maschner for enabling African researchers to participate in global digital heritage projects, from France and Italy to Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, with upcoming work planned for Rwanda and Malawi.

“At this time, when we are grappling with how to decolonise engineering education, it is important that this initiative helps to uncover the stories and achievements of people whose contributions were long silenced,” he said.

Esterhuyzen praised UCT’s support for interdisciplinary collaborations. “It is this work, in partnership across disciplines, that will move our understanding of the African past to an entirely new level.”

Together with Maschner and Motala, she urged postgraduate students to join this unprecedented research effort.

“Our mission does not end with discovery,” Malgas concluded. “The data we are creating is our gift to the future. It is for our scholars, for our students, and most importantly, for the communities who call South Africa home.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.