UCT team’s central role in R5-bn settlement

20 August 2019 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Michael Hammond. Read time 7 min.

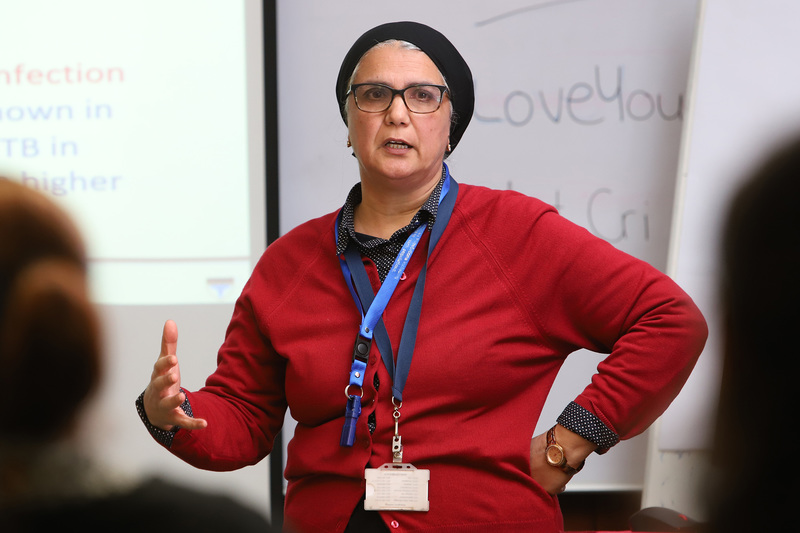

University of Cape Town (UCT) academics Dr Shahieda Adams and Professor Mohamed Jeebhay were part of a team that played an integral role in providing technical medical input to the legal arguments in South Africa’s historic R5-billion settlement for the gold miners who contracted silicosis and/or pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) at work.

This was highlighted by attorney Charles Abrahams at a recent seminar at UCT, during which he said their contribution to the technical team was important in gathering the evidence to make the link between TB and silica exposure. This link has historically not been adequately compensated, unlike the case with other dust-related lung diseases, due to the mining industry not accepting full culpability.

The settlement marked an important milestone in the fight not only against TB, but also for workers’ rights and for improved industry exposure standards.

South Africa continues to struggle with the TB epidemic, carrying one of the highest burdens of the disease worldwide. Despite available treatments and the South African government’s concerted efforts to tackle the disease, TB remains one of the leading causes of death in the country.

“It is not common knowledge that those who are exposed to silica have far higher rates of TB.”

On 26 July 2019, the Gauteng High Court in Johannesburg made its historic ruling in favour of mineworkers affected by silicosis and/or pulmonary TB. It was historic for the R5-billion settlement but also for the inclusion of TB as being eligible for compensation.

The case was first proposed in 2012 and certified as a class-action lawsuit in 2016. It was organised by Richard Spoor Incorporated Attorneys, Abraham Kiewitz Inc and the Legal Resources Centre.

The six mining companies that have agreed to pay compensation are African Rainbow Minerals, Anglo American, AngloGold Ashanti, Gold Fields, Harmony and Sibanye-Stillwater. These six companies form the Occupational Lung Disease (OLD) working group.

Over the next 12 years, the R5-billion settlement will be distributed through a fund administered by the Tshiamiso Trust. Affected mineworkers and the families of those who have lost their lives will receive between R70 000 and R500 000, depending on the claimant class. These classes, of which there are 10, are based on the severity of their conditions.

Making the link

Silicosis is an occupational lung disease caused by the inhalation of silica dust, and is particularly prevalent in gold mines. The case for including TB in the class action was more complex. But adamant to do so, human rights attorney Charles Abrahams approached Jeebhay and Adams.

The two specialists, who are based at the Division of Occupational Medicine at UCT’s School of Public Health and Family Medicine, are familiar with class-action lawsuits, having contributed to both the Macassar sulphur dioxide disaster and the asbestos-related illness class actions.

Their job in this instance was specific: They were to assemble a team of experts to focus on the link between silica exposure and TB.

“We see it as our role as engaged scholars to be dealing with these big issues.”

TB is complex because there are multiple risk factors, including poverty, overcrowding and a high rate of HIV co-infection.

In mineworkers as a group, many of these risk factors come into play: They live in poor-quality and overcrowded hostels, rates of HIV are high amongst them, and many seek to make a living on very low wages.

In the light of a high background prevalence of community-acquired TB, confounded by these factors, there has been very little research done on the link between silica dust and TB, making it convenient to rule out the former as an important risk factor for the latter. But Adams and Jeebhay are aware that silica stays in the lungs and contributes to disease over time, due to the immune system being unable to clear the silica particles. This makes mineworkers more vulnerable to contracting TB.

“It is not common knowledge that those who are exposed to silica have far higher rates of TB,” said Adams.

High infection rate

Studies of ex-miners in the Eastern Cape have shown that a third of gold-mine workers in that province have silicosis and/or TB. Additionally, the rate of infected gold mineworkers in some areas is three to six times higher than in the general population. These same rates of infection are not evident in platinum and diamond mine workers, for example.

“So, from a biological point of view, it is really plausible that [silica] increases risk,” said Adams.

Being an occupational medicine consultant and heading the Occupational Medicine Clinic at Groote Schuur Hospital where ex-mineworkers are seen every week, provided good exposure to better understanding the clinical presentations of these workers in relation to their mine dust exposures.

By combining the available – albeit scarce – research, Adams’s clinical work and her PhD research analysing TB in healthcare workers, she and Jeebhay, together with other technical team members, made a case for the plausibility of the link to TB in silica-exposed workers.

This has, for the first time in South Africa, forced mining employers to accept that TB can be caused by high levels of silica dust present in gold mines.

“We are quite pleased … because it’s a significant leap in terms of accepting liability for a disease that, historically, has ravaged this country.”

“We are quite pleased … because it’s a significant leap in terms of accepting liability for a disease that, historically, has ravaged this country,” said Jeebhay.

For Adams and Jeebhay, contributing and translating their expertise in class-action suits speaks to their role as academics in promoting issues that address environmental and social justice.

Teaching opportunities

Jeebhay, head of the Division of Occupational Medicine, said the higher purpose of their job as clinicians and academic scholars is to ensure that working people are employed, healthy and productive. When the system fails workers, it’s about helping them get back on their feet and into the economy again.

The gold-mining case has implications for other industries where workers are exposed to silica: quarries, ceramics, sandblasting and stone engraving, to name a few.

Experience in class-action suits also makes for rich teaching opportunities. Jeebhay and Adams share their research with students, ensuring their teaching remains current, and with a greater academic audience.

Students are taught about circumstances and elements beyond biological factors that promote and cause disease and disability. They also learn to work with lawyers, negotiate with employers and gain a better understanding of how to speak to workers about diseases.

Jeebhay added that their involvement in class-action suits illustrates that the university is engaging with issues “at this interface with big social problems”.

“[UCT] is there to … protect human rights, protect the environment, assist with social security issues [and] with health,” he said.

“We see it as our role as engaged scholars to be dealing with these big issues.”

Overall, though, Jeebhay and Adams’s work is about improving society.

“We want people to have a good quality of life, gainful employment and opportunities that, historically, they have not had access to,” said Jeebhay.

“For us, if these things are addressed, you feel that there is at least some justice in the world.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.